This is Naked Capitalism fundraising week. 1314 donors have already invested in our efforts to combat corruption and predatory conduct, particularly in the financial realm. Please join us and participate via our donation page, which shows how to give via check, credit card, debit card, PayPal, Clover, or Wise. Read about why we’re doing this fundraiser, what we’ve accomplished in the last year, and our current goal, Karōshi prevention.

In this discussion, we delve into the theories of justice articulated by Matt Bruenig, who meticulously explores concepts of economic and distributive justice. At its core, these theories ask a fundamental question: are the outcomes of our economic systems fair according to some standard of fairness?

Bruenig highlights that many individuals resonate with meritocratic ideas, suggesting that distributions should reflect deservingness or “desert.” However, this notion is often challenged by economists and philosophers who argue that the concept of “desert” collapses when applied to capital ownership.

By Matthew Bruenig, an American lawyer, blogger, policy analyst, commentator, and founder of the People’s Policy Project. Originally published at his website

My fascination with economic philosophy and distributive justice began during high school and college, where I sought to define criteria that determine the fairness of resource distribution in society. When I launched this website in 2011, I explored these themes extensively, including two notable pieces on desert theory published in 2014 and 2015, which gained traction in recent discussions on X. Nowadays, I rarely address these subjects, although I did create a one-hour YouTube video on desert theory a few years back.

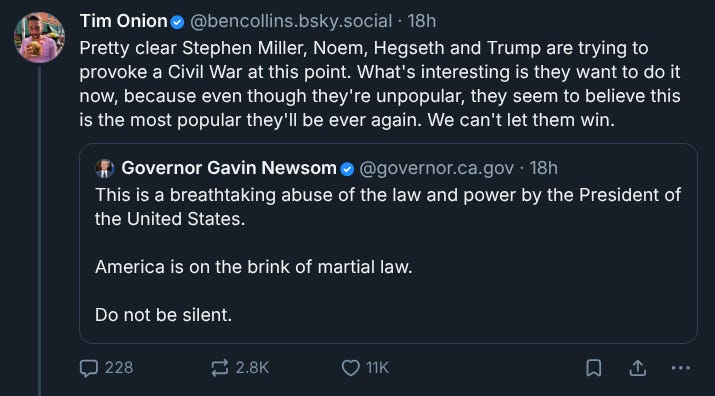

Engagement on X regarding this topic often reflects a mix of confusion, misunderstandings, and intentional misinterpretations. Attempts at clarification usually don’t make much of a difference, as much of the discourse on X tends to favor in-group validation over factual correctness. Nonetheless, I enjoy discussing this topic and am eager to share my evolved perspective after a decade of contemplation.

There are several competing theories of distributive justice, including:

- Desert — A fair distribution grants each individual a share based on their contributions.

- Utilitarianism — A fair distribution maximizes overall happiness or well-being in the population.

- Egalitarianism — A just distribution aims to enhance equality or improve the status of the most disadvantaged.

- Voluntarism — A distribution is just if it arises from voluntary economic interactions.

- Democracy — A just distribution is determined through laws that have democratic legitimacy.

While these theories provide a simplified framework for understanding distributive justice, they illustrate two distinct approaches: the first three focus on the distributive results, while the latter two regard the process that yields these results.

As philosopher Chris Frieman pointed out in discussions on X, most defenses of capitalism presented by economists and political philosophers hinge on efficiency or rights, rather than desert theory. The reference to “efficiency” appears to align with utilitarianism, while “rights” may pertain to voluntarism or natural rights theories.

My observations suggest Frieman is correct: capitalist philosophers rarely reference desert in their arguments, a stark contrast to the general public, which often invokes this concept. An earlier piece of mine responded to Noah Smith’s use of desert theory, and the subsequent discussions on X were rife with attempts to justify capitalist income distributions through this lens.

Desert Theory

To substantiate the claim that capitalist distributions reflect desert, one must accomplish two tasks:

- Define the criteria or characteristics that determine deservingness, often referred to as the “desert base.”

- Demonstrate that capitalist distributions align in a way that mirrors the defined desert base, meaning individuals with higher desert levels (or “more desertils”) receive more than those with lower levels (“less desertils”). Additionally, those with identical desert levels should receive equal shares.

The simplest approach to construct an argument under desert theory is to examine the capitalist distribution and establish a desert base that corresponds to that outcome. At that stage, critics can challenge the chosen desert base or reject desert theory entirely. However, if one cannot even identify a valid desert base that aligns with capitalist distributions, their argument collapses.

But what could this desert base for capitalist distributions be? Is there a viable definition?

For labor income among workers, one reasonable desert base might be personal productivity: more productive individuals tend to earn more, while those who are less productive earn less, with comparably productive workers receiving similar compensation. While this view presents potential objections, it provides a starting point.

However, personal productivity fails as a desert base for capital income. As Joan Robinson noted, even if we assert that capital is inherently productive, “owning capital is not a productive activity.” This aligns with my earlier commentary on X, questioning whether capitalists genuinely earn their capital income, comparing it to a thought experiment in which capital is managed without owner involvement.

Interestingly, the non-productiveness of capital ownership isn’t limited to blind trusts. The income derived from interests, dividends, rents, and capital gains is disconnected from any actual work or productivity on the part of the owners. This phenomenon allows individuals—even those incapacitated or deceased—to receive capital income through estates or transfers, unlike labor income that is inherently linked to tangible work.

Given that personal productivity does not substantiate capital income, a desert-based argument for capitalism must either abandon it for another desert base or expand it with supplementary factors.

One approach might involve including “undertaking risk” as a contributing factor for capital income. This was one of the points made by Noah Smith during our debate a decade ago, relevant to much of the recent discourse on X.

While it’s possible to describe capital ownership as inherently risky, the distribution of capital income doesn’t conform to this desert base. In my previous work, I illustrated this by presenting a scenario of three individuals—Persons A, B, and C—who are identical except that A and B take risks by investing in financial assets, while C opts to keep cash under a mattress, resulting in the following outcomes:

- Person A earns $1,000 from a successful investment.

- Person B loses $100 on a failed investment.

- Person C maintains the same amount without gain or loss.

This outcome contradicts the principles of desert, as Person A’s gain exceeds Person B’s, despite their equal risk levels. Even Person C ends up better off than Person B, highlighting the failure of the desert base to validate capital income distributions.

In response to critiques of my analysis on X, many often stated that:

- Risk inherently leads to unequal returns for individuals undertaking similar risks.

- Equalizing rewards among identical risk-takers would undermine the functionality of capital markets and capitalism.

To this, I assert:

- Indeed, the mechanics of risk compensation fundamentally conflict with desert theory.

- Exactly. The nature of capitalism clashes with any desert-based framework.

Many negative reactions stem from readers misconstruing excerpts and failing to grasp their role in my overarching argument about capitalism and desert. In some cases, participants may simply struggle to follow philosophical discourse, making it challenging to distinguish between the notions that “a desert theory emphasizing risk should provide equal rewards” and “I advocate for equal compensation for all risk-takers.” Whether clarifying my stance on desert further confuses them or not remains uncertain.

Responses to my argument often shift toward attempts to validate capital income via other theories of distributive justice, such as utilitarianism and voluntarism. While I have much to say regarding capitalism’s compatibility with these approaches, it’s crucial to emphasize that utilitarian or voluntarist justifications differ from destractionist claims, highlighting a fundamental incompatibility between capitalism and desert theory.