Recent developments in Mexico’s wage policy highlight that improving conditions for low-income workers does not automatically lead to increased unemployment or inflation.

Nearly a month ago, President Claudia Sheinbaum of Mexico announced a 13% rise in the country’s minimum daily wage, which will increase from 278 pesos to 315 pesos in 2026. In higher-wage northern border regions, the increase will be 5%, bringing the minimum daily wage to 440 pesos.

This wage adjustment is set to benefit approximately 8.5 million Mexican workers, as confirmed by Labour Minister Marath Bolanos, who stated it resulted from a negotiation involving leaders from labor, business, and government sectors.

A New Year’s Tradition

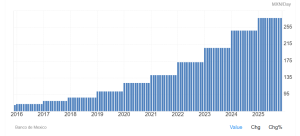

In Mexico, significant annual salary increases have recently become a New Year tradition. Since 2018, the minimum daily wage has risen almost four-fold in nominal terms, from a mere 88 pesos (just under $5) under former President Enrique Peña Nieto to the current rate of 315 pesos ($17.50).

According to the graphic below, provided by Trading Economics, there have been seven substantial hikes in the minimum wage since December 2018, excluding the newest increase that is about to take effect.

After accounting for official inflation, the latest increase marks a cumulative rise of 154% over the past eight years. Many critics, including political opponents, business figures, and economists, initially cautioned that this approach would spark inflation and increase unemployment.

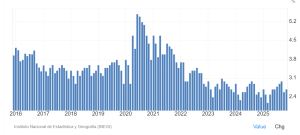

However, none of these predictions materialized. Currently, Mexico has an official unemployment rate of just 2.7%, nearing its lowest on record. This has occurred despite the challenges posed by fluctuating tariffs from the United States and uncertainties surrounding the USMCA trade agreement review.

As illustrated in the graph below, provided by Trading Economics, unemployment levels have actually decreased over the past three years compared to the period preceding Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s election in 2018.

This eight-year initiative to raise the minimum wage has positively impacted the incomes of millions of Mexicans, lifting approximately 13.4 million individuals out of poverty without jeopardizing their employment prospects.

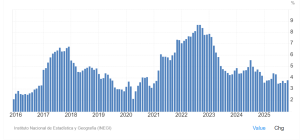

Since 2018, Mexico’s inflation rates have fluctuated, peaking at 8.7% in 2022. However, this surge was mainly driven by pent-up demand and global supply chain disruptions following the reopening of economies post-COVID-19 lockdowns. In fact, Mexico’s peak inflation rate was lower than those of several OECD countries, including the US (9.1%), the UK (11.1%), and Spain (10.8%).

The current Consumer Price Index in Mexico stands at 3.8%, which is one percentage point lower than in late 2018, when the minimum daily wage was about 70% less than it is now.

As Luis F Munguía, president of Mexico’s National Minimum Wage Commission, discusses in a thought-provoking article for Phenomenal World, one of the primary reasons inflation has not surged following the substantial minimum wage increases is that the starting minimum wage was excessively low.

In May 2016, CNN’s Spanish division conducted a study comparing minimum statutory wages across Latin American countries relative to their performance on the Big Mac index, with the US Dollar as a benchmark. At that time, Mexico ranked last among 13 countries, even behind smaller economies like El Salvador and Guatemala.

In that period, the legal minimum wage in Mexico was just 74 pesos, or around $4 per day—approximately $0.50 an hour. In comparison, Brazil’s minimum wage was $1.40, Peru’s was $1.45, Ecuador’s and Chile’s were both $2.07, Argentina’s was $2.38 (soon to increase by 33%), and Uruguay’s was $2.43.

A minimum-wage worker needed to work 5.6 hours to afford a Big Mac—more than triple the time it took a Salvadoran worker to earn the same meal. This highlights that Mexico had significantly lower purchasing power compared to its neighboring countries.

As I mentioned in a previous article for WOLF STREET, while the Big Mac index isn’t a perfect metric, it remains a useful tool for assessing currency value:

The Economist created the Big Mac index in 1986 as a lighthearted way of gauging whether currencies are fairly valued. Since then, it has become a standard reference point included in numerous economic textbooks and the subject of extensive academic research. As The Economist itself recently acknowledged, a more accurate gauge of currency value would be the relationship between Big Mac prices and GDP per capita, leading authors to find that the Mexican peso was undervalued by 43%.

Reversing a 70% Loss in Purchasing Power

So, how did one of the largest economies in Latin America end up with one of the region’s lowest minimum wages? The response involves a mix of economic turmoil (including hyperinflation in the late ‘70s, the “lost decade” of the 1980s, and the 1994 Tequila Crisis), corporate greed, and trade liberalization, as recounted by Munguía:

In 1976, after nearly three decades of progressive growth, the minimum wage peaked at $20.76 per day (adjusted to 2025 terms). However, the subsequent year brought an economic crisis dominated by hyperinflation and widespread unemployment. The government responded by freezing wage adjustments below the rate of inflation, leading to a 75% loss in purchasing power over ensuing decades.

Transitioning into the 1990s, Mexico adopted a neoliberal economic model emphasizing trade liberalization and deeper integration within North America. To remain competitive on a global scale, the government opted to suppress wages, maintaining the daily minimum wage at approximately $5.25 (in today’s currency) from 1990 to 2017, with only a marginal increase at the end of this period due to mounting social pressures.

The turning point came in 2018 under López Obrador, when there was increasing public demand for wage enhancements. A team of economists from the Colegio de México assessed how to increase the minimum wage without destabilizing the economy, resulting in a gradual, feasible recovery strategy aimed at restoring lost purchasing power over seven years.

Notably, Munguía points out that this process began in 2016, during Peña Nieto’s administration when constitutional reforms aimed at “de-indexing” the minimum wage were established:

This action was taken in response to warnings from business and labor sectors, which both argued that wage increases were unfeasible due to potential inflation spirals. This concern was partly justified, as many economic aspects were linked to the minimum wage. For instance, fines in various cities were expressed in minimum wage terms, certain loans were similarly indexed, and many collective agreements tied wage increases and benefits to the minimum wage.

Therefore, it was crucial to decouple these standards. In 2014, under public pressure, the Mexico City government proposed the necessity to increase and de-index the minimum wage, leading to formal proposals in 2015 supported by labor representatives. Ultimately, in 2016, the minimum wage was successfully separated from these economic indices, allowing for subsequent increases.

The first double-digit increase occurred in December 2018, implementing a 16.9% rise nationwide, with higher increases in the Northern Border Free Zone where the minimum wage doubled. This was intended as a controlled trial before extending the plan nationwide, and despite significant opposition from businesses warning of inflation, the initial data showed that inflation remained lower in the North than in the rest of the country, dispelling the notion that raising the minimum wage leads directly to inflation.

Since then, the Mexican government has enacted seven additional double-digit increases to the national minimum wage. With the 2024 raise, the minimum wage surpassed those in half of Latin America, according to Munguía, and these hikes have been key in elevating 6.64 million individuals out of poverty between 2016 and 2024—approximately half of the total 13.4 million people lifted from poverty.

Despite this progress, each wage raise continues to face resistance from significant business segments, even though higher wages often boost domestic demand and consumption:

Initially, the business sector repeatedly claimed that raising the minimum wage would instigate inflation. However, as evidence emerged showing low or even lower inflation in regions with elevated minimum wages, this argument lost credibility. Furthermore, data has indicated that the Mexican job market exhibits monopsonistic characteristics, with no discernible correlations between minimum wage increases and employment reductions.

With each increase, businesses expressed concern, particularly regarding rising labor costs, even though they indirectly benefited from increased consumer spending. Fortunately, ongoing research has frequently highlighted the benefits of enhancing workers’ incomes to strengthen the domestic economy.

Initially, unions were somewhat cautious regarding wage increases, echoing business concerns. Ironically, union leaders expressed more trepidation than their corporate counterparts, despite international examples demonstrating positive outcomes for workers. However, unions have grown more assertive over time, even proposing increases beyond what was initially set.

Next Target: a 40-Hour Work Week

Mexico’s success with minimum wage increases should not come as a surprise—particularly outside elite academic circles. As previously indicated by Yves, foundational studies by David Card and Alan Krueger have shown that minimum wage hikes do not inherently lead to job losses.

Germany’s recent implementation of a minimum wage revealed similar outcomes, despite warnings of potential job losses that never came to fruition.

In Mexico, the substantial salary increments between 2018 and 2024 were pivotal to Claudia Sheinbaum’s decisive electoral victory in 2024. Who would have expected that enhancing the living standards of society’s poorest could translate into political success?

Looking ahead, the Sheinbaum administration has proposed a significant labor reform awaiting approval in 2026: gradually instituting a 40-hour work week, reducing the current 48-hour week by two hours annually from 2027 to 2030. Just like the minimum wage rises, this reform will have a profound impact on millions of Mexican workers.

Mexico currently holds the record for the longest working hours among OECD nations, tallying 2,207 hours per year in 2023. Of the 13.4 million individuals working over 40 hours weekly, 8.6 million record hours between 41-48, while 2.76 million clock in 49-57 hours, based on data from INEGI (as relayed by Mexico News Daily). Additionally, around two million individuals work over 58 hours weekly.

This proposed reform also aims to establish limits on daily working hours (12) and the number of days workers can be requested to work overtime (four days). Furthermore, it entails that overtime must be compensated at double the standard rate, prohibiting overtime for employees under 18.

Meanwhile, Colombia’s outgoing Gustavo Petro administration is raising the minimum wage by 22.7%. Yet, media outlets like Reuters are already predicting spikes in inflation and unemployment—a concern reminiscent of past discussions.

As seen, Mexico’s experience demonstrates that responsible wage policy can uplift the workforce without inciting economic chaos, setting a hopeful precedent for the region.