The United States has long relied on its naval power to exert influence globally. An anchored cruiser served to signal compliance or risk consequences. This strategy, known as gunboat diplomacy, was built on the foundation of naval dominance, quick deployment, and the expectation that smaller nations would be unable to resist. However, the dynamics of power projection have evolved significantly.

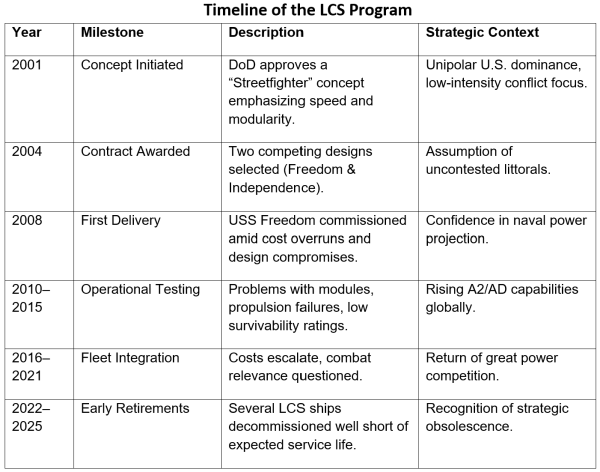

The Littoral Combat Ship (LCS), designed in the early 2000s for rapid military action in shallow coastal waters, is now being phased out. Its failure illustrates more than just a procurement blunder; it signifies the decline of an era when the U.S. Navy could operate near foreign shores and expect to command submission instead of resistance. This article delves into the various shortcomings of the LCS program and its implications for coercive diplomacy.

A Solution for a Misguided Mission

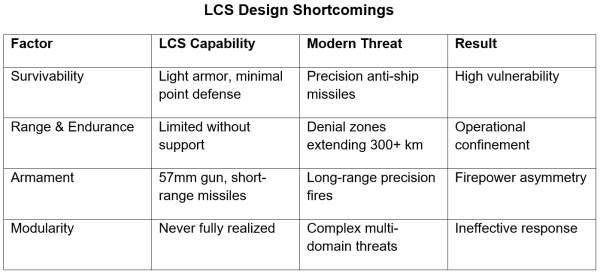

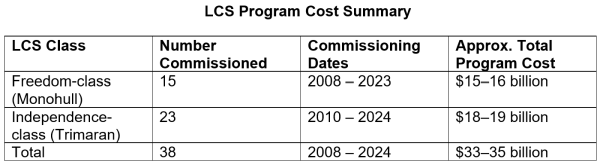

The LCS was created to bridge the operational divide between large surface warships and smaller patrol vessels. It aimed to showcase U.S. naval strength in coastal regions where larger ships might be at a disadvantage, leveraging speed, flexibility, and a minimal crew. Two distinct classes were developed—the Freedom-class and the Independence-class. Both boasted high speeds (over 40 knots), modular mission packages, and light armament. Unfortunately, this approach proved fundamentally flawed. The mission modules never delivered the expected capabilities, mechanical issues were pervasive, and the vessels lacked adequate protection against contemporary threats. They were too fragile for intense combat while being too costly for simple deployments.

Freedom class LCS

Independence class LCS

Two Designs, One Program: An Inherent Weakness

The Littoral Combat Ship program was unique in that it simultaneously approved two entirely different designs instead of selecting one. This approach reflected both strategic ambiguity and institutional dynamics. Officially presented as a competitive procurement strategy to cut costs and foster innovation, it instead contributed to confusion. The two designs—the monohull Freedom-class and the trimaran Independence-class—emanated from differing engineering philosophies.

However, the decision stemmed from a deeper uncertainty. During the early 2000s, the Navy lacked a definitive operational concept for littoral warfare; endorsing two designs served as a hedge against fluctuating strategic conditions. Political considerations also played a role: by supporting both Fincantieri Marinette Marine and Austal USA, Congress ensured more jobs and reduced chances of cancellation.

While the Navy intended to choose a single design after testing, both classes entered production, creating a fragmented fleet with incompatible training and maintenance processes, duplicative logistics, and soaring lifecycle costs. This dual-design framework exacerbated the program’s numerous shortcomings and is now recognized as a foundational mistake.

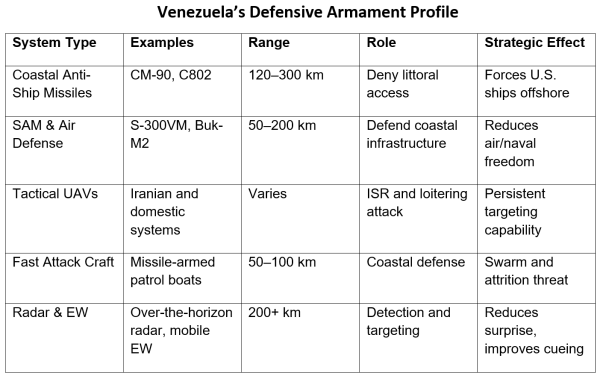

The End of Gunboat Diplomacy

Gunboat diplomacy was effective in the past because major powers had naval assets capable of intimidating coastal states without fear of retaliation. However, the rise of Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2/AD) technologies has radically changed this landscape. Coastal-targeted systems, such as the Chinese C-802 anti-ship missile, can now pose threats to naval operations. Ballistic and cruise missiles like the DF-21D extend these denial zones far from shore, while loitering munitions and drone swarms enhance surveillance and strike capabilities. Sophisticated air defense systems have made invading coastal areas risky, even for nations without traditional navies.

The LCS, designed for agility and speed, is inadequately armed and poorly shielded, reliant on mission modules that failed to deliver the necessary capabilities. In contested waters—like the Persian Gulf, South China Sea, or Caribbean—LCS vessels would confront layered threats from land-based missiles, UAVs, and submarines. As a result, the deployment of U.S. naval forces is no longer a cost-effective or low-risk option, but rather a potentially costly liability.

Convergent Failures: Program Development and Foreign Policy Strategy

The failure of the Littoral Combat Ship program resulted from a convergence of poor procurement practices and outdated foreign policy assumptions. The program was born from the belief that projecting naval power would remain largely uncontested along global coastlines. This led to ships that prioritized speed, modularity, and cost over combat effectiveness and survivability. Compromises were made, believing that advanced mission modules would counterbalance the ships’ inherent weaknesses—an assumption that ultimately proved unfounded.

At the same time, U.S. foreign policy persisted in its reliance on the principles of gunboat diplomacy, assuming that the presence of American warships would translate into leverage. This positioning was formulated during a time of unipolar dominance and failed to adapt to shifting global dynamics. As the Navy constructed specialized vessels intended for benign environments, potential adversaries invested in advanced A2/AD systems, precision strike capabilities, and unmanned platforms that could threaten U.S. surface ships economically.

The interplay of these two failures only intensified the issues. A platform poorly equipped for an obsolete strategy was introduced in a time when that very strategy was no longer viable. Consequently, the LCS became not only a procurement failure but also a strategic relic, illustrating how procurement dysfunction, institutional inertia, and geopolitical complacency can yield weapons systems rendered outdated upon their introduction.

Venezuela and the Challenges of U.S. Naval Coercion

The Trump administration has aimed to replace the Maduro regime in Venezuela through military strategy. While a naval coercion campaign would have been straightforward in the 1990s, the situation has changed drastically. Although Venezuela lacks a blue-water navy to challenge the U.S. fleet, it compensates with a range of shore-based missiles, air defenses, and surveillance technologies, creating a zone that renders operations by lightly armed vessels like the LCS precarious. Even a significant U.S. naval presence could encounter formidable resistance from Venezuela.

C-802 anti-ship missile

This shift is not an isolated case; countless mid-sized and smaller nations now possess sophisticated precision weapons and integrated defense systems. Deterrence, once exclusive to major powers, has become more accessible. The assumption that U.S. naval forces can operate freely near foreign shores is increasingly questionable. The growth of precision munitions has made effective deterrence economically viable. Unmanned systems enable surveillance and strike capabilities without necessitating extensive fleets, while electronic warfare erodes American advantages in early detection and mobility. The failure of the LCS program embodies this new reality: littoral waters are now contested spaces.

The Yemen Missile Campaign: A Case of Failing Gunboat Diplomacy

The Littoral Combat Ship program reflects the theoretical breakdown of gunboat diplomacy, while the Yemen missile campaign illustrates its operational failure. Since late 2023, U.S. and allied naval forces have established a robust presence in the Red Sea with advanced surface combatants and carrier strike groups to deter attacks on international shipping. Despite significant U.S. firepower, air support, and continuous surveillance, the blockade campaign by the Houthi Ansar Allah military persisted largely unchallenged until the recent ceasefire in Gaza.

Yemen is not a major military power; it lacks a blue-water navy. Its military effectiveness is based on mobile launchers, anti-ship cruise missiles, and UAVs, many of which are inexpensive or supplied by external sources. These dispersed and concealed weapons have enabled a weaker actor to disrupt global shipping despite the U.S. Navy’s presence.

This scenario underscores a critical shift in the strategic landscape: naval presence no longer guarantees effective control. Modern shore-based strike systems can outperform, outmaneuver, and outprice traditional naval deployments. The cost of a single missile battery is a fraction of that of a U.S. destroyer, yet poses the same level of threat. This asymmetry challenges the core of gunboat diplomacy. The Red Sea campaign has revealed what the LCS reflects: the age of intimidation through offshore warships has come to an end.

Recognizing LCS Failure

The U.S. Navy has quietly accepted the shortcomings of the Littoral Combat Ship (LCS) program. Initially designed to yield over 50 vessels, the operational effectiveness proved so limited that, by the mid-2020s, many were earmarked for early retirement—some with fewer than ten years of service.

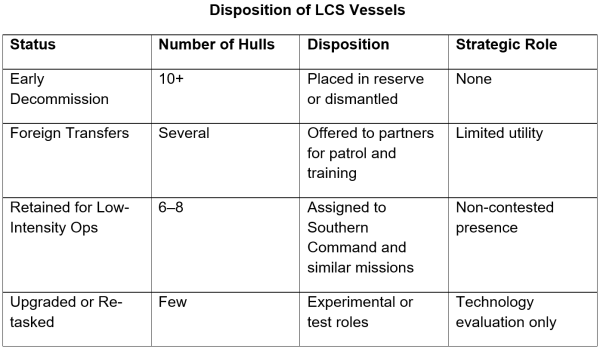

High-ranking Navy officials informed Congress that the ships were unsuitable for contested environments. Budget documents redirected funds away from modernizing the LCS fleet in favor of more capable frigate and destroyer programs. Mission modules, once considered an innovative feature, were effectively abandoned due to repeated cost overruns and technical difficulties. Consequently, the Navy’s long-term shipbuilding strategy reclassified most LCS units as non-combatant or auxiliary vessels. Several LCS ships have been decommissioned early, repurposed for reserve use, or stripped for spare parts. Others have been offered to allies for training or transfer. A few remain for low-intensity operations like counter-narcotics missions in safer zones.

Conclusion

The failure of the LCS program represents more than just a misstep in naval design; it embodies a larger trend of strategic complacency—a vessel envisioned for a paradigm that no longer exists. The impending retirement of LCS ships signals that the time of effortless naval coercion has ended. The fundamentals of gunboat diplomacy relied on overwhelming, inexpensive, and reliable military presence, a framework now rendered obsolete. The emergence of precise weaponry has transformed deterrence into an accessible strategy for many nations. Moving forward, U.S. maritime strategy must acknowledge that the ability to project naval power cannot be taken for granted. Future deployments of warships to “send a message” may no longer ensure the intended response.