Sign up for the Slatest to receive insightful analysis, criticism, and advice delivered to your inbox daily.

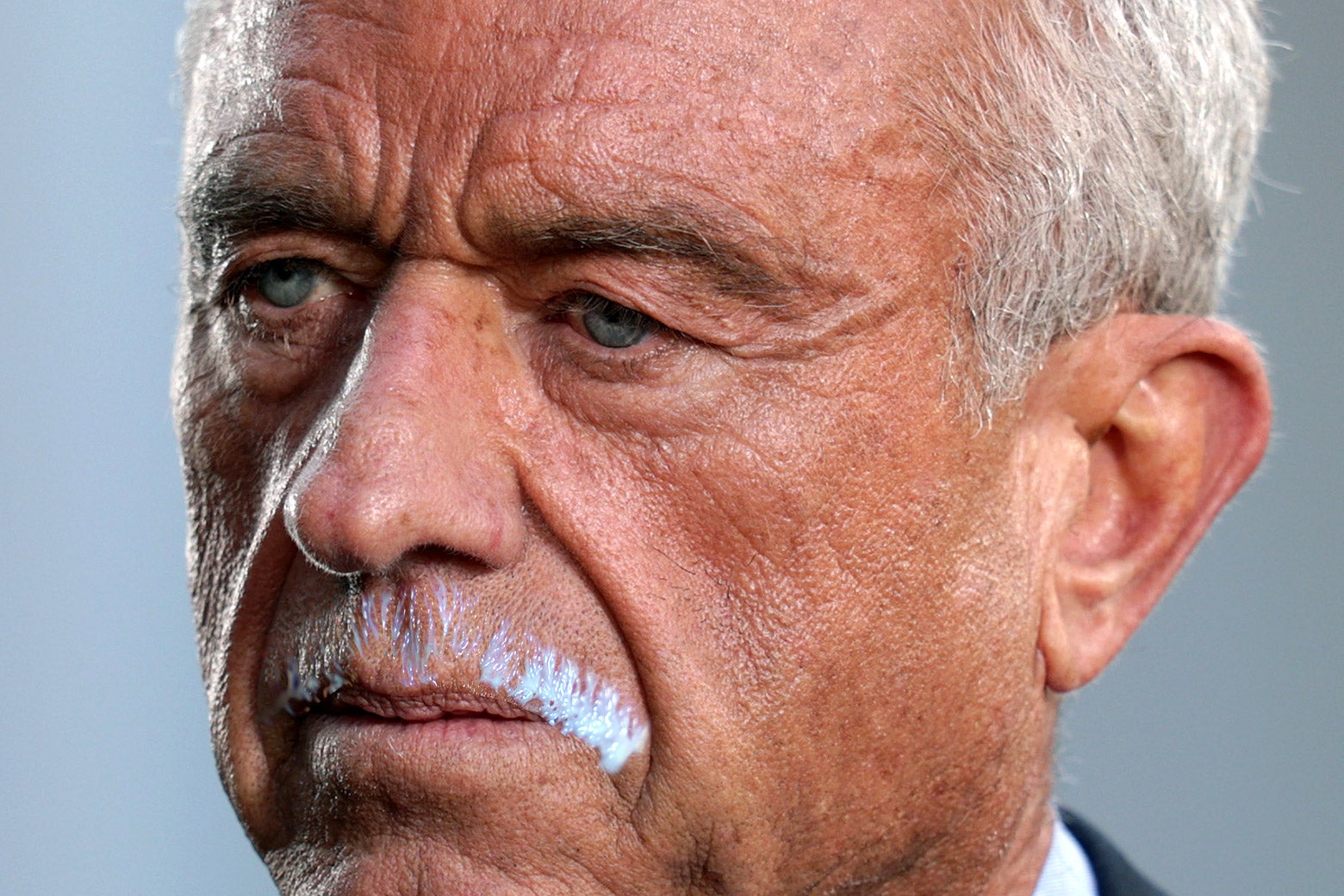

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has a notable affection for whole milk. Last autumn, his health administration proclaimed that the “war” on whole milk was over. Recently, he shared an AI-generated video of himself enjoying whole milk while dancing, complete with a milk mustache. His new dietary guidelines highlight whole milk, recommending three daily servings of “full-fat” dairy, stating, “Dairy is an excellent source of protein, healthy fats, vitamins, and minerals.”

However, from a scientific perspective, the recommendation for full-fat dairy is puzzling. Virtually all milk available in supermarkets is processed to be similar. Given the MAHA’s focus on whole milk, one might assume it offers more vitamins and minerals than skim milk. In reality, it simply contains more fat.

To understand this, we need to consider milk production. Each cow produces milk with varying fat-to-cream ratios. If left unprocessed, fresh milk forms a thick cap of cream that must be mixed back in to avoid unpleasant chunks while drinking. (As someone who had non-homogenized milk as a child, I can attest: It’s not ideal to find a glob of fat in your cereal because you forgot to stir.)

The process to address this issue is called homogenization. This high-pressure technique evenly distributes fat throughout the milk, ensuring that by the time it reaches consumers, the cream is fully blended. The only differences between whole, 1 percent, and skim milk are the varying fat contents.

Aside from the fat content, all milk types available are practically identical. One percent milk carries the same amount of protein, vitamins, and minerals as whole milk. You—and perhaps RFK Jr.—might believe that whole milk is more “natural,” given its name. However, nearly all supermarket milk undergoes processing, which is beneficial.

What whole milk does indeed contain more of is saturated fat. The Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services promotes consuming saturated fat and publicly urges people to increase their intake. Strong evidence links saturated fat consumption to heart health, with substantial studies indicating that it raises bad cholesterol levels. Elevated bad cholesterol is associated with cardiovascular diseases, which means that reducing it can help prevent cardiovascular issues. Hence, lowering the intake of saturated fat is generally considered beneficial.

Interestingly, RFK Jr.’s dietary guidelines align with this scientific understanding, as they recommend keeping saturated fat intake at 10 percent of daily calories—advice consistent with prior nutritional guidance. However, this recommendation contradicts the guidelines on full-fat dairy and RFK Jr.’s enthusiasm for whole milk. If one were to consume whole milk for the suggested three servings of dairy daily, they could quickly reach their saturated fat limit from milk alone. While this isn’t inherently harmful, it necessitates careful monitoring of further saturated fat intake—a task that RFK Jr. seems less inclined to prioritize. Consequently, adhering to the recommendations for both full-fat dairy and the 10 percent saturated fat guideline while using RFK Jr.’s preferred beef tallow for cooking becomes quite challenging.

Moreover, RFK Jr. suggests that eliminating whole milk has caused children to turn to sugary alternatives. He argues that without whole milk options, kids will opt for sugary drinks. While it’s true that excessive consumption of soda or sweetened milk is unhealthy, this rationale doesn’t justify promoting whole milk. It’s akin to saying if people are replacing Tylenol with oxycodone, we should just distribute aspirin. The current evidence doesn’t definitively prove that whole milk is healthier; some studies indicate minor benefits from lower-fat alternatives instead. Although one shouldn’t consume substantial saturated fats, the choice of milk for cereal probably isn’t a significant factor in overall health.

Interestingly, the scientific framework for these guidelines hints that whole milk might not be as beneficial as suggested. The appendix states: “We need definitive RCT data to determine whether whole-fat dairy intake will improve the metabolic health of American children.” RCT refers to “randomized controlled trial,” which aims to establish whether consuming whole milk is genuinely healthier—a study typically performed before altering guidelines in confusing ways.

So, should you choose whole milk or skim? Based on the available evidence, there isn’t a compelling reason to favor either option. Whole milk is essentially similar to reduced-fat alternatives, with the primary distinction being the fat content. While whole milk contains slightly more calories—450 for three cups versus 300 for 1 percent milk—the difference isn’t drastic. The additional saturated fat isn’t ideal, but its health impact is likely minimal in such small quantities. While everyone agrees that chocolate milk is unhealthy, similar logic implies that opting for skim milk is advantageous if you’re looking to lose weight or lower cholesterol. Overall, from a scientific perspective, there’s insufficient justification to endorse one milk type over another.