Yves here. While those familiar with AI trends may find the headline unsurprising, it’s crucial to highlight a significant issue: AI’s growing demand for electricity is being increasingly satisfied by fossil fuels, undermining the progress made in electricity decarbonization.

By Alessandra Bonfiglioli, Rosario Crinò, Mattia Filomena, and Gino Gancia. Originally published at VoxEU

While AI and other data-driven technologies can enhance energy efficiency, they are also notably energy-intensive. This column examines the impact of AI’s proliferation on emissions in the US from 2002 to 2022. The findings indicate that increased AI activity correlates with elevated emissions due to enhanced economic activity and energy consumption, leading to a shift in energy generation towards more carbon-intensive sources. The purported environmental benefits of AI are likely to remain unattainable unless the electricity sector transitions to cleaner energy swiftly.

Measuring the carbon footprint of AI has become a pressing necessity. Policymakers are considering whether the rising electricity demand linked to AI might impede decarbonization efforts. It is anticipated that data centers, which are integral to supporting AI models, will represent 8% of US electricity demand by 2030, a significant increase from 3% in 2022 (Davenport et al., 2024). Concerns have arisen that this surge might delay the decommissioning of coal power plants. Conversely, AI and digital technologies are frequently marketed as ‘green’ innovations that could enhance efficiency and reduce emissions.

Previous studies on digitalization waves (e.g., Lange et al., 2020) revealed that while information and communication technology could mitigate certain waste forms, the net effect often resulted in increased energy consumption. More recent evidence links cryptomining to rising local electricity costs (Benetton, 2023), and ongoing discussions question if data center expansion will prolong reliance on fossil fuels within power grids (Electric Power Research Institute, 2024; Knittel et al., 2025).

Our recent study (Bonfiglioli et al., 2025) addresses this concern by offering systematic insights into how AI adoption has influenced emissions in the US over the past 20 years. Our results suggest that the environmental promises of AI will not materialize without a rapid transition to cleaner electricity production.

A Comprehensive Dataset Linking AI, Data Centers, and Power Plants

For our analysis, we developed a unique dataset connecting AI, emissions, and the locations of data centers and power plants across 722 US commuting zones from 2002 to 2022. This timeframe aligns with the emergence of the digital economy, cloud computing, and early AI applications. We conceptualize AI as algorithms harnessed for big data analysis, using changes in employment within data-centric roles—such as software developers, data scientists, and systems analysts—sourced from the O*NET database (Bonfiglioli, Crinò, Gancia, and Papadakis, 2024, 2025).

We also charted the geographical locations of over 2,000 data centers, linking them to nearby power plants and their energy sources. Additionally, emissions data were extracted from the high-resolution Vulcan dataset (Gurney et al., 2009, 2025), which monitors CO2 emissions from fossil fuel combustion segmented by sector and locality, supplemented with satellite data on alternative pollutants.

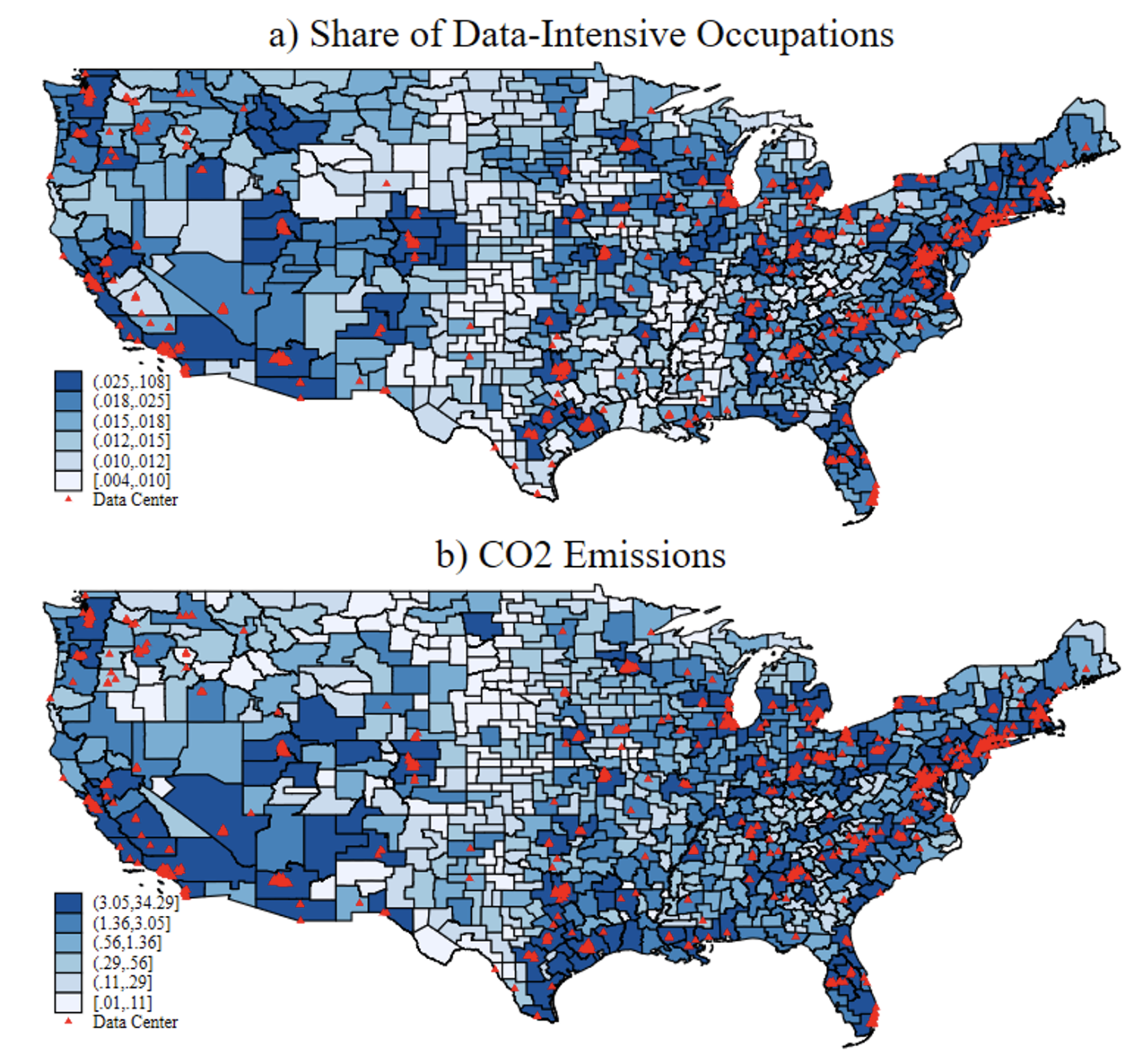

Figure 1 presents color-coded maps illustrating how employment in data-centric roles (panel a) and CO2 emissions (panel b) fluctuate across US commuting zones, with darker shades signifying heightened levels of adoption or emissions during the sample period. Red triangles indicate data center locations. The data suggest that regions with greater employment in data-intensive fields tend to exhibit increased emissions, which may be linked to their proximity to data centers. However, this correlation does not imply causation, as both AI adoption and emissions could be influenced by external factors.

Figure 1 Data-intensive occupations, data centers, and CO2 emissions

Notes: Panel (a) shows the employment share of data-intensive occupations in each commuting zone for 2022. Panel (b) displays total CO2 emissions in those zones for the same year. Darker colors indicate higher levels of adoption of data-intensive roles or emissions throughout the sample period, with red triangles marking the presence of a data center.

To account for the possibility that AI adoption could be influenced by local economic conditions, we employed a shift-share (Bartik) instrument. We identified commuting zones that were historically more exposed to AI based on their specialization in industries that demonstrated faster growth in data-centric roles than the national average.

The Impact of AI on Emissions

Our analysis reveals four critical insights. Firstly, AI hampers the green transition at the local level. Regions specializing in industries with rapid growth in data-intensive employment experienced significantly slower declines in CO2 emissions (Figure 2). Emissions dropped by an average of 16% from 2002 to 2022. Conversely, in a hypothetical commuting zone with zero AI exposure, CO2 emissions would have decreased by 37% more than the average. Although these figures shouldn’t be interpreted as counterfactual scenarios, they imply that local AI influence raises emissions compared to areas with less exposure.

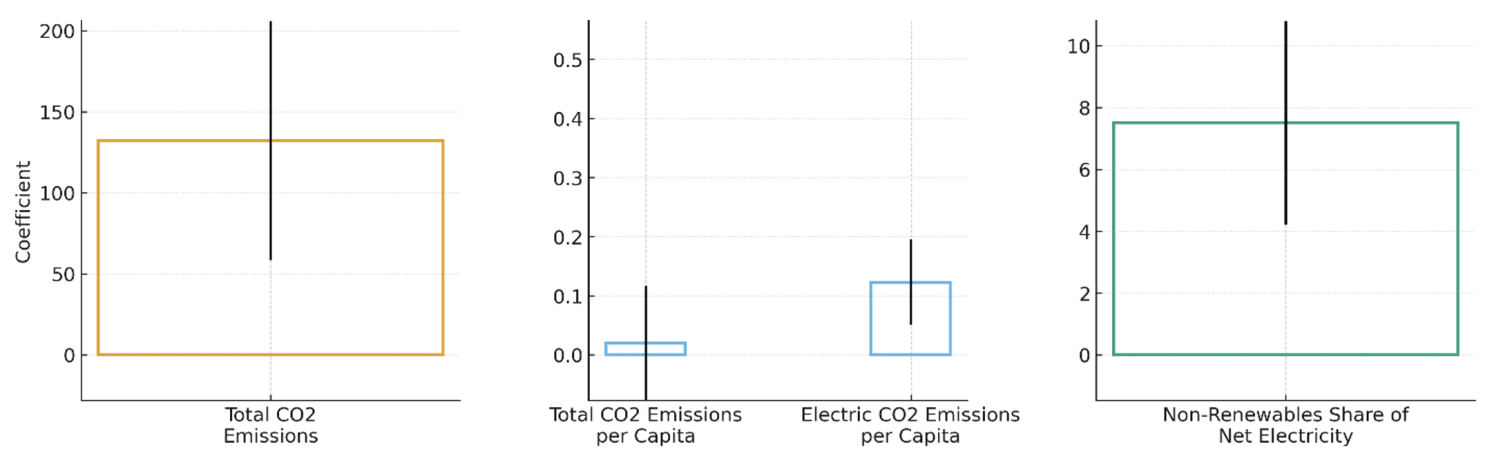

Figure 2 AI penetration, CO2 emissions, and electricity generation

Notes: This figure presents estimated coefficients and 90% confidence intervals regarding the effects of AI penetration on various emissions types and the share of non-renewables in net electricity generation. The estimation sample includes 722 commuting zones analyzed across four 5-year periods from 2002 to 2022.

Secondly, the emission increase primarily results from a scale effect. Analyzing the factors driving emissions—scale, composition, and technique (Levinson, 2009)—revealed that local economic growth is the main channel through which AI contributes to emissions. Areas with rapid data-intensive employment growth attracted more businesses and workers, leading to increased overall output and, consequently, energy usage (Figure 2). Shifts in industrial composition slightly reduced emissions rather than exacerbating them.

Thirdly, electricity generation shifts towards more carbon-intensive sources. Even when considering scale, per capita emissions from electricity generation increased in areas with higher AI adoption (Figure 2). This occurs because power plants in regions with significant AI penetration transition from renewable to non-renewable energy production (Figure 2). This confirms fears that the energy demand stemming from AI applications and data centers is primarily met by fossil-fuel plants, which provide the consistent energy supply necessary for high-performance computing.

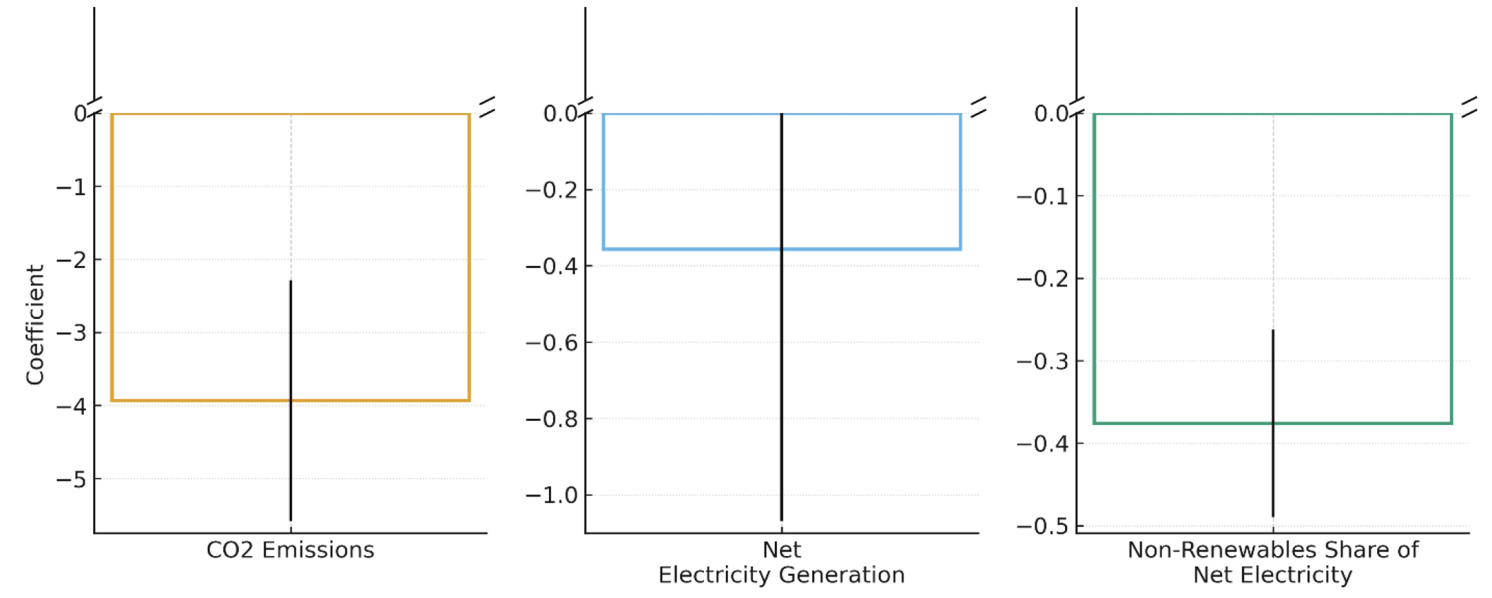

Our fourth and final finding highlights the significance of data center locations. As electricity cannot be stored efficiently on a large scale, the grid must constantly balance supply with demand. Given the high transmission loss costs, power plants are influenced by nearby energy demands, particularly from data centers that require a stable, high-capacity electricity supply. Consistently, we found that proximity to data centers correlates with power plants generating higher CO2 emissions and relying more heavily on fossil energy sources (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Distance to data centers and power plant activities

Notes: This figure shows estimated coefficients and 90% confidence intervals for the effects of power plants’ average distances from data centers on various operational metrics. The analysis includes 11,500 power plants observed across four 5-year periods from 2002 to 2022.

Conclusions

These findings quantify a concern that climate experts have frequently expressed: without a more rapid transition to low-carbon energy sources, the spread of AI could impede or even reverse recent progress in emissions reduction.

Importantly, our study examines the period from 2002 to 2022, before the emergence of generative AI. While the anticipated efficiency gains from these newer technologies may eventually facilitate decarbonization, training and operating contemporary large language models require substantially more energy than earlier AI applications included in our dataset. Without significant investment in renewable energy, the upcoming wave of AI could impose even greater short-term emissions impacts.

Our research underscores an uncomfortable reality: digital transformation and decarbonization cannot remain distinct agendas. The rise of AI exemplifies a classic dilemma of technological advancement: innovations promising long-term efficiency can, in the short term, exacerbate environmental challenges by increasing energy demand. The objective should not be to hinder AI progress but to accelerate the transition to clean energy. This may necessitate incentives for more energy-efficient hardware, strategically locating data centers in areas with ample clean energy, and enhancing transmission infrastructure. Absent this strategic alignment, the pursuit of increasingly powerful algorithms may inadvertently entrench economies on a path of higher emissions.

For references, see the original post