Yves here. This article takes a detailed look at the profound and lasting economic impacts of war, illustrating that their consequences are often more severe than commonly perceived.

By Efraim Benmelech, Harold L. Stuart Professor of Finance and Director, Guthrie Center for Real Estate Research, Kellogg School of Management, Northwestern University and Joao Monteiro, Einaudi Institute for Economics and Finance (EIEF). Originally published at VoxEU

Wars inflict deep and enduring wounds on economies. Analyzing data from 115 conflicts across 145 countries over the last 75 years, this piece reveals significant and lasting decreases in output, investment, and trade following the outbreak of war, with little indication of recovery even a decade later. Government revenues plummet while expenditures remain stable, leading to an increased reliance on inflationary financing and short-term debt. These findings illuminate that the true costs of war extend far beyond the battlefield, fundamentally altering fiscal and monetary stability for many years.

The global landscape is once again gearing up for conflict. Military expenditures have surged to levels not seen since the Cold War, propelled by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, escalating tensions in the Middle East and East Asia, and an increasing realization that peace can no longer be taken for granted. Governments are rushing to boost their defense budgets even as they grapple with strained public finances, persistent inflation, and rising interest rates. The fiscal and macroeconomic implications of this renewed arms race could be far-reaching; however, research on how wars impact economies has been surprisingly limited.

Some recent studies have begun to address this gap. For instance, a column on VoxEU by Yuriy Gorodnichenko and Vittal Vasudevan suggests that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine may incur costs upwards of US$2.4 trillion, with lasting output losses of at least fifteen percent for the involved nations (Gorodnichenko and Vasudevan 2025). Another study (Federle et al., 2024a) finds that major conflicts can reduce GDP by over 30% within five years and lead to persistent inflationary pressures (VoxEU, 2024). Additionally, a related analysis (Harrison 2023) discusses how governments financed total wars using debt, inflation, and coercive state measures. These contributions rest on a broader academic foundation documenting the extensive economic toll of conflict—from Abadie and Gardeazabal (2003) on the Basque Country to Collier (1999) on civil wars, Cerra and Saxena (2008) on significant and enduring growth losses, as well as the long-term scars of war highlighted by Blattman and Miguel (2010), implications on war finance from Barro (1987) and Harrison (1998), and fiscal-monetary consequences explored by Hall and Sargent (2014, 2022) and Federle et al. (2024b) concerning the international spillovers of conflict.

A New Global Dataset on the Economics of War

In our recent study (Benmelech and Monteiro 2025), we present the first extensive cross-country evidence on the macroeconomic impacts of war on combatant nations. Our dataset encompasses 115 conflicts across 145 countries over the past 75 years, incorporating both interstate wars (state versus state) and intrastate wars (state versus non-state actors).

Employing a stacked event-study design, we compare belligerent nations (not concurrently involved in other conflicts) to never-treated control nations, utilizing fixed effects for both conflict-country and conflict-region-year to account for time-invariant factors and regional trends.

GDP Collapses – and Does Not Recover

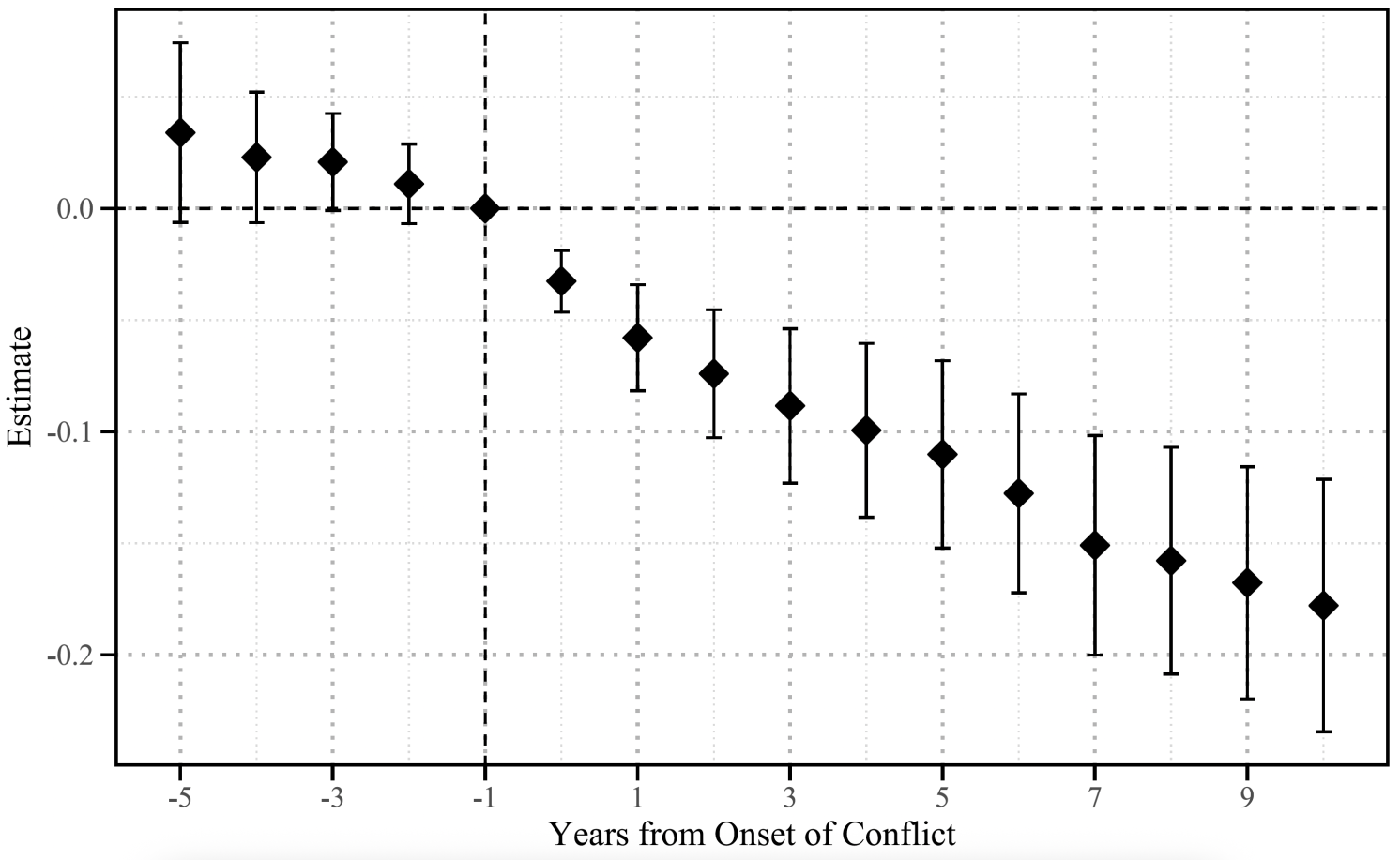

Our findings indicate that real GDP declines by approximately 12% over a decade for conflict-affected countries in comparison to control countries, reflecting an absolute loss exceeding $28 billion (in 2015 prices). Initially, the decline is modest (around 3.3%), but it intensifies to about 16% after ten years. Notably, consumption and investment fall drastically; exports decrease by 12%, and imports by 7%, contributing to a current account deterioration of around US $2.1 billion.

Figure 1 Effect of conflict on GDP

War is also associated with the destruction of capital stock. One might expect investment to rebound due to the increased marginal productivity of capital; however, our observations reveal a substantial decline, with real investment falling by approximately 13%, and real domestic credit decreasing by 20%—outpacing the overall output loss. Lending rates do not decrease, which dismisses weak demand as a cause and instead indicates a tightening of credit supply.

This decline can be interpreted as evidence that conflict erodes collateral values, restricting borrowing, especially in lower-income countries characterized by shallow financial markets. Additionally, the adverse effects of war are markedly more pronounced in low-income nations, where investment declines are steeper, trade disruptions are more considerable, and the reliance on imported capital goods exacerbates the economic shock.

Fiscal Collapse and the Short-Term Debt Trap

Conflict also places immense pressure on public finances. We document that real government revenues plummet by about 14%, while real government debt decreases by nearly 9%, despite nominal debt rising in local currency. Meanwhile, government spending remains relatively stable, leading the debt-to-GDP ratio to hold steady; however, the underlying real dynamics signal fiscal vulnerability.

Moreover, we find that the proportion of long-term debt declines by approximately 2.2 percentage points (about 1.2% of GDP) as governments transition to short-term debt to manage risks and limited access to financing. This shift is financially significant, reallocating 1.2% of GDP from long-term to short-term debt and increasing rollover risks, leaving these already weakened economies more susceptible to financial crises.

Inflation: The Silent Tax of War Finance

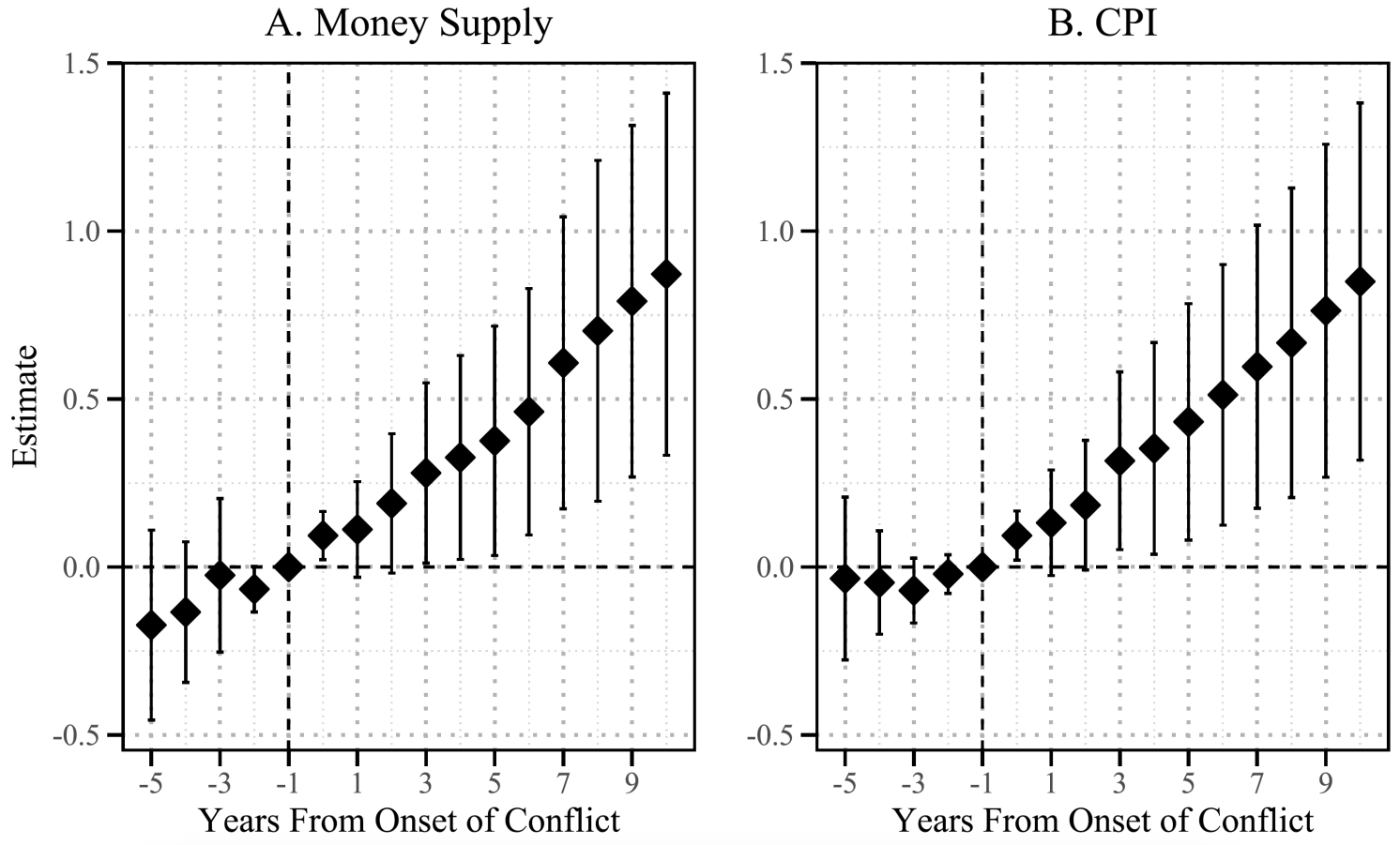

In the decade following the onset of war, we observe a consumer price level increase of approximately 62%. Concurrently, the nominal money supply rises by about 67%, yet real money balances remain unchanged, indicating an inflationary approach to financing government deficits rather than real cash reserves. War triggers a scenario of fiscal dominance, where deficits, monetization, and inflation become interconnected.

Figure 2 Effect of conflict on CPI and money supply

Policy Lessons: The True Cost of War

The main takeaway from our analysis is clear: the costs of war are not mere temporary disruptions; they are extensive, enduring, and multifaceted. Wars do not only devastate capital and infrastructure; they also undermine the very financial and monetary foundations necessary for modern economies to thrive.

For policymakers confronting escalating geopolitical risks and a resurgence of major military mobilization, several considerations become crucial:

- It is vital to uphold credible fiscal and monetary frameworks, particularly in wartime, since the manner in which conflicts are financed significantly affects their long-term impacts.

- Reconstruction does not occur automatically. Without access to credit, stable institutions, and affordable capital goods, economies may languish in stagnation for ten years or longer.

In summary, although treaties may mark the end of conflicts, the economic scars of war persist long afterwards. Acknowledging the enduring nature of these scars should inform our strategies for both waging and recovering from war.

See original post for references