In recent years, China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has spurred significant international attention regarding its impact on global investments, particularly among major strategic contenders like the US, Japan, and the UK. This study investigates how these countries have adapted to China’s growing influence through the BRI, revealing a diverse array of strategic responses. Notably, the US has ramped up its investments in countries engaging with the BRI, likely motivated by both defensive strategies and enhanced profit opportunities.

By Yasuyuki Todo, Professor in the Faculty of Political Science and Economics Waseda University, Shuhei Nishitateno, Professor Kwansei Gakuin University; Research Associate Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI), and Sean Brown. Originally published at VoxEU

The Belt and Road Initiative has significantly transformed international economic and political relationships, leading to a reorganization of global value chains. This analysis highlights the varied strategic responses from major investing nations based on their economic and political ties with China. In contrast to the US, which increased investments in BRI countries to maintain competitive advantages, the UK scaled back investments due to concerns over geopolitical risks. Japan’s investment trajectory appears largely unaffected by its strategic posture towards China.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative was initiated in 2013 with an early focus on developing transportation networks linking China with Asia, Europe, and Africa, later expanding its scope to include energy and digital projects. By 2024, a total of 149 nations had signed Memorandums of Understanding (MoUs) with China, facilitating US$71 billion in construction contracts and $51 billion in investments—the highest levels recorded since the initiative’s inception (Nedopil 2025). Therefore, the BRI has not only altered international economic relations but has also reorganized global value chains.

Research surrounding the BRI’s impact often investigates its effects on trade and foreign direct investment (FDI), which play crucial roles in global value chains. Typically, studies indicate that FDI from China to BRI nations has risen, likely attributed to improved infrastructure that reduces production and transport expenses, coupled with strengthened political ties that mitigate investment uncertainties (Nugent and Lu 2021, Yu et al. 2019, among others).

The BRI also appears to influence FDI from countries outside of China for various reasons. Enhanced infrastructure can draw in FDI from diverse nations, and involvement in the BRI can signify closer political alignment with China, reflecting China’s ambition to expand its international reach (Huang 2016).

In this context, Western countries uncomfortable with China’s international aspirations may respond differently to BRI countries. If they perceive investments in these nations as increasing political risks, Western nations might curtail their FDI. Conversely, if they view the need to compete with China for political and economic influence, they may actually ramp up their investments.

Our study (Todo et al. 2025) examines how FDI patterns into BRI countries differ among various Western powers, including the US, Japan, and European nations. We applied staggered difference-in-differences (DID) estimations to global bilateral FDI data, revealing that the BRI has prompted diverse strategic reactions among major investing nations based on their economic and political dynamics with China. The findings demonstrate that investments today are influenced not only by economic considerations but also by political and security factors.

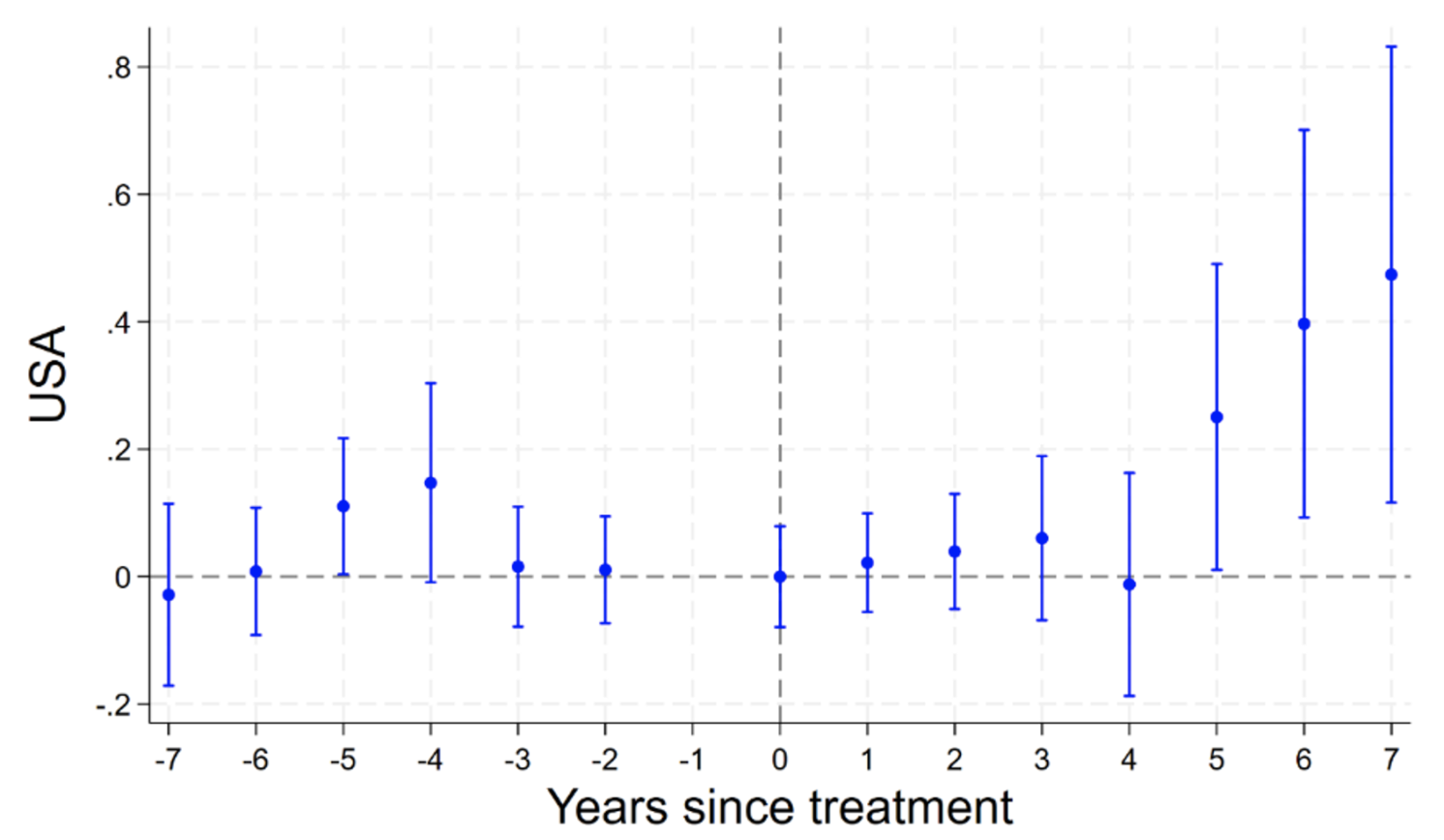

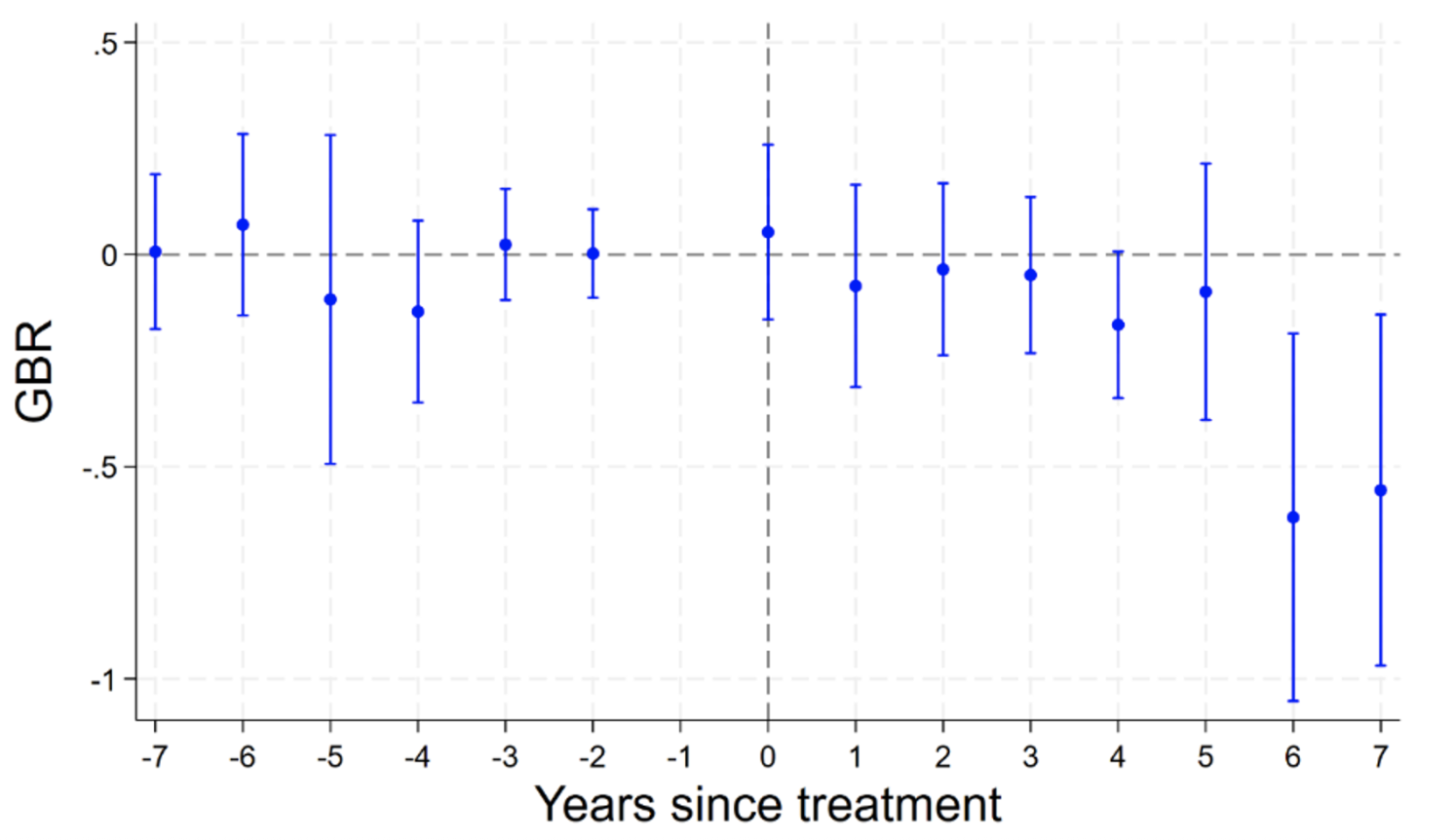

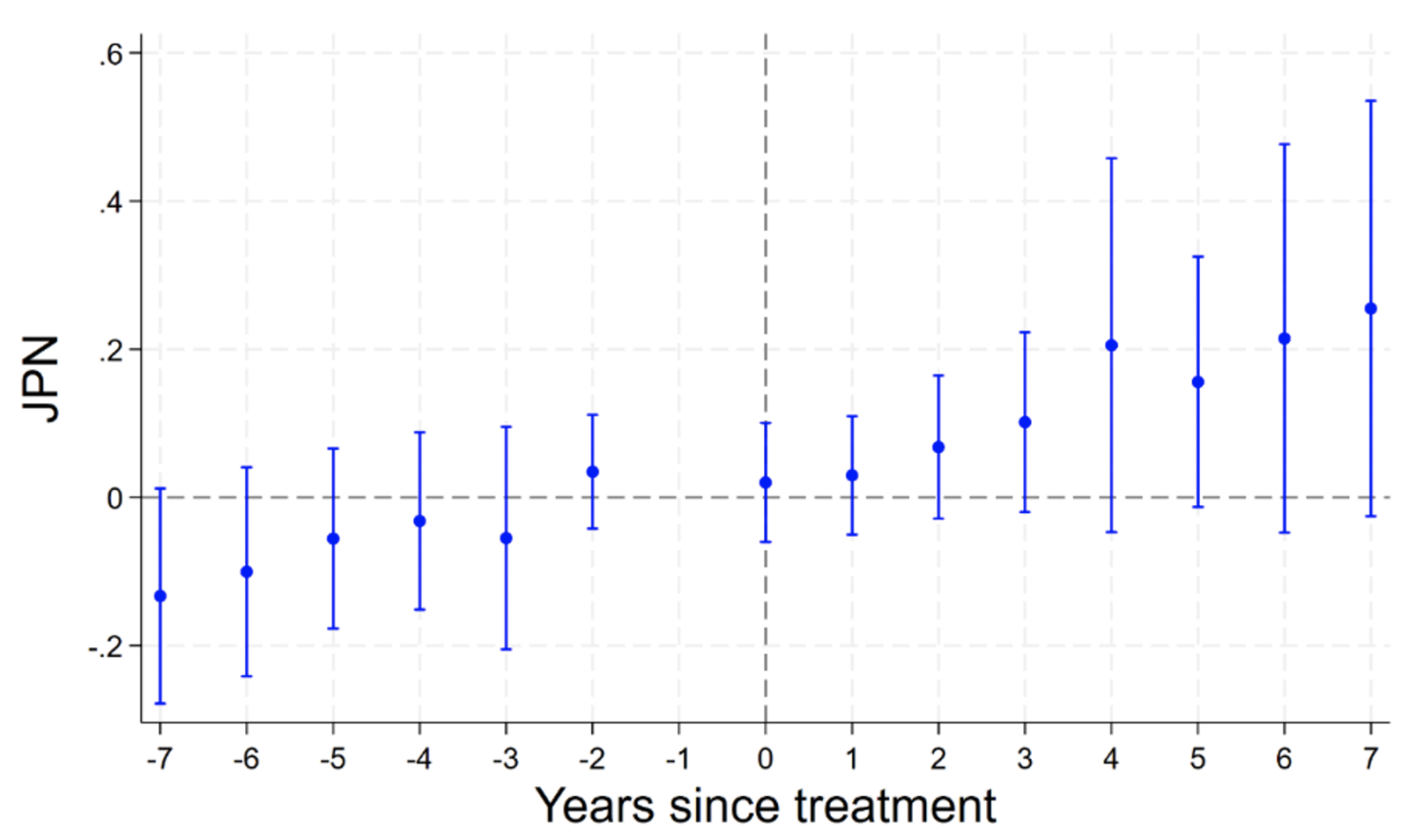

Figure 1 FDI from Major Western Investors to BRI Countries

a) United States

b) United Kingdom

c) Japan

Note: The horizontal axis illustrates years since one year prior to signing an MOU between China and the BRI country.

The US: Competing Against China Through FDI in BRI Countries

Our empirical data indicates that, despite its refusal to join the BRI, the US has increased its investment in BRI countries following their MoUs with China, as evidenced in Panel (A) of Figure 1. Our research suggests that strategic rivalry is a primary driver behind this investment surge.

China’s ascendance as an economic and technological powerhouse, bolstered by its increasing alliances through the BRI and other initiatives, has intensified the US-China rivalry (Li 2021). The US has sought to provide alternatives to the BRI through initiatives such as the Blue Dot Network and the G7’s Build Back Better World (Savoy and McKeown 2022), making FDI a vital aspect of this strategy.

American firms and development finance institutions have focused their investments on the same sectors—particularly infrastructure and energy—where China is most active. A case in point is former US President Biden’s visit to Angola in December 2024, where he launched a 1,344 km railway project in collaboration with other G7 nations to rival Chinese investments in Angola’s railway system (BBC 2024).

This scenario underscores a crucial understanding: the BRI doesn’t simply deter Western engagement; in many cases, it provokes further investment.

The UK: Cautious of Supply Chain Risks Linked to BRI Countries

In contrast, the UK has notably reduced its FDI in countries participating in the BRI (Panel (B) of Figure 1). This withdrawal stems from escalating concerns over political and supply chain risks associated with China, particularly after 2018 when issues surrounding 5G technology, intellectual property transfer, and national security became pressing. By 2019, the UK government officially classified China and the BRI as presenting “systemic challenges,” reflecting a significant shift in policy (Ashbee 2024).

Contemporary research into global supply chains highlights their susceptibility to foreign economic shocks arising from geopolitical tensions (Alfaro and Chor 2023). Efforts by UK firms to mitigate potential supply chain disruptions appear to have negatively impacted their FDI in BRI countries.

Japan: A More Subdued Approach Toward the BRI

The patterns of Japanese investment are less pronounced. Our analysis indicates that while FDI from Japan to BRI countries increases post-participation, this rise is statistically insignificant (Panel (C) of Figure 1). This suggests that the positive effects stemming from strategic competition with China and the negative implications of avoiding investments in less favorable BRI countries tend to offset one another.

Moreover, when controlling for host-country fixed effects, we find that Japanese FDI remained relatively stagnant before and after the BRI’s initiation. This suggests that factors not explicitly reflected in the data—such as infrastructure quality and institutional potential—have contributed to the minor, albeit statistically insignificant, upward trend in Japanese FDI in BRI countries post-initiative.

The Role of Autocracy in Investment Patterns

Further analysis shows that the political landscapes of BRI countries also influence FDI, with autocratic nations attracting higher FDI from both China and the US compared to their democratic peers. This aligns with China’s inclination to partner with regime-friendly nations, where infrastructure projects often face fewer transparency hurdles (Huang 2016). For the US, this finding supports the interpretation that investment in autocratic BRI countries is driven by strategic concerns over aligning with nations likely to fortify their ties to China.

What Should the West Consider Going Forward?

Historically, the BRI faced criticism for contributing to debt crises and labor disputes within member nations. However, the recent initiatives led by US President Trump—including imposing high tariffs, closing USAID, and cutting down on foreign aid—have made certain Global South nations more amenable to aligning economically and politically with China. In response, China has increased its investments in BRI projects to record levels in 2024, following a dip during the COVID-19 pandemic (Nedopil 2025).

Our findings illustrate that Western nations have not uniformly increased their FDI in response to the BRI. Nevertheless, reduced economic ties with the Global South could lead to heightened vulnerabilities in supply chains for Western countries, as diversified supply chains tend to enhance resilience (Ando and Hayakawa 2021, Kashiwagi et al. 2021). Moreover, diminishing economic relationships may also weaken political alliances. Therefore, it may be essential for Western nations to recalibrate their strategic approaches towards the BRI and bolster economic and political connections with developing nations to enhance supply chain resilience and safeguard national security.

For references, see the original post