In this article, we will explore how both advanced and emerging economies can effectively address the critical issues of high public debt and stagnant growth. By redirecting government spending towards productivity-boosting sectors such as infrastructure and healthcare, along with enhancing the overall efficiency of government operations, countries can foster economic growth. This discussion assumes that the nations in question, similar to Eurozone member states, lack monetary sovereignty. However, even economically independent nations often face resistance from fiscally conservative groups.

Notably, even Larry Summers, a prominent economist with a moderate Keynesian inclination, emphasized that investment in infrastructure can yield returns exceeding the original outlay—especially in a country like the US, which grapples with significant infrastructure needs—potentially generating GDP growth up to threefold compared to the expenditure incurred.

Despite this, many advanced economies have adopted a neoliberal narrative suggesting that privatization and private ownership of public services, especially in areas like infrastructure, lead to greater efficiency. However, the costs linked to complex legal arrangements and fundraising for these projects render such claims questionable, particularly considering that all newly constructed public toll roads in the US have gone bankrupt. As discussed in 2021:

A notable example of inefficiency is toll roads. A 2014 article analyzing privatization trends pointed out how new toll road ventures invariably face financial collapse. There is little evidence that the structure or conditions of these agreements have improved to benefit users and taxpayers. From Thinking Highways:

The evidence suggests that public-private partnerships for toll operations primarily serve as vehicles for international financiers, leading to planned bankruptcies. Typically, the U.S. government backs the bonds, representing the bulk of “private” funds. When a private toll road or tunnel operator declares bankruptcy, taxpayers are left to cover the bonds alongside any public loans provided, essentially subsidizing the failure while the parent company retains toll revenues and bears no penalties for cost overruns.

Shockingly, no American private toll companies appear to remain operational under the same management fifteen years post-construction. The original companies often declare bankruptcy or abandon their assets, leaving taxpayers responsible for maintenance and bond repayment.

The scale of bankruptcies spans from Virginia’s Pocahontas Parkway to San Francisco’s Presidio Parkway and many others worldwide, including Australia’s Airport Link and several toll facilities in South Carolina and California.

Furthermore, no private toll entities have met their pre-construction traffic projections. Even those firms that avoid bankruptcy often generate only half of the anticipated revenue for investors and government stakeholders.

Beyond the evident public financial burdens posed by bankruptcies, privatizing infrastructure tends to yield poor outcomes for citizens. Financial backers frequently exploit these assets by raising fees, such as airport landing charges, while skimping on necessary maintenance, as exemplified by the inefficiencies in U.S. healthcare, which suffers from high costs and poor results due to misaligned profit incentives. Compounding this issue, both the EU and the U.S. are poised to increase spending on overpriced military arms.

While policymakers might consider more effective proposals, they often need to navigate significant intellectual biases and corruption before enacting changes. Unfortunately, indicators suggest that existing inertia and ineffective leadership will likely exacerbate these conditions, particularly for those already at a disadvantage.

PS: It’s important to note that while the authors of this article are affiliated with the IMF, there exists a longstanding division within the organization. The research division has consistently advocated for progressive reforms, while the program side tends to adhere to a more rigid neoliberal enforcement stance.

By Era Dabla-Norris, Deputy Director, Fiscal Affairs Department, International Monetary Fund; Davide Furceri, Division Chief, Fiscal Affairs Department, International Monetary Fund; Zsuzsa Munkacsi, Economist, International Monetary Fund; and Galen Sher, Economist, International Monetary Fund. Originally published at VoxEU.

With high public debt and sluggish medium-term growth, finance ministries are challenged to maximize effectiveness with limited resources. This column posits that global efficiency gaps in public spending range from 30-40%, particularly pronounced in infrastructure and R&D expenditure. By reallocating funds to infrastructure, education, health, and research and development, while simultaneously closing efficiency gaps, emerging market and developing economies could raise GDP by approximately 11%, and advanced economies by around 4%, over the longer term, all without increasing overall spending.

Recent IMF forecasts indicate that global public debt could exceed 100% of GDP within the next four years. Rising interest rates, increased defense spending, and the demands of aging populations create a climate where every dollar of public expenditure must work diligently to yield better results. Adding to this complexity, growth outlooks have remained tepid since the COVID-19 pandemic.

The IMF’s October 2025 Fiscal Monitor suggests that nations have extensive opportunities to reallocate public spending, potentially enhancing value-for-money by about one-third through adopting best practices (IMF 2025). The report indicates that smart spending—achieved through better prioritization and increased efficiency—can boost GDP by 11% in emerging markets and 4% in advanced economies over the longer term.

Scope for Reforms

Since the 1960s, the proportion of public spending relative to GDP has doubled in both advanced and emerging market nations; yet, the allocation remains non-productive for economic growth. Globally, public infrastructure investments have decreased by two percentage points as a share of total spending, while expenditure on public education has remained stagnant at around 11%—less than half of public wage bills.

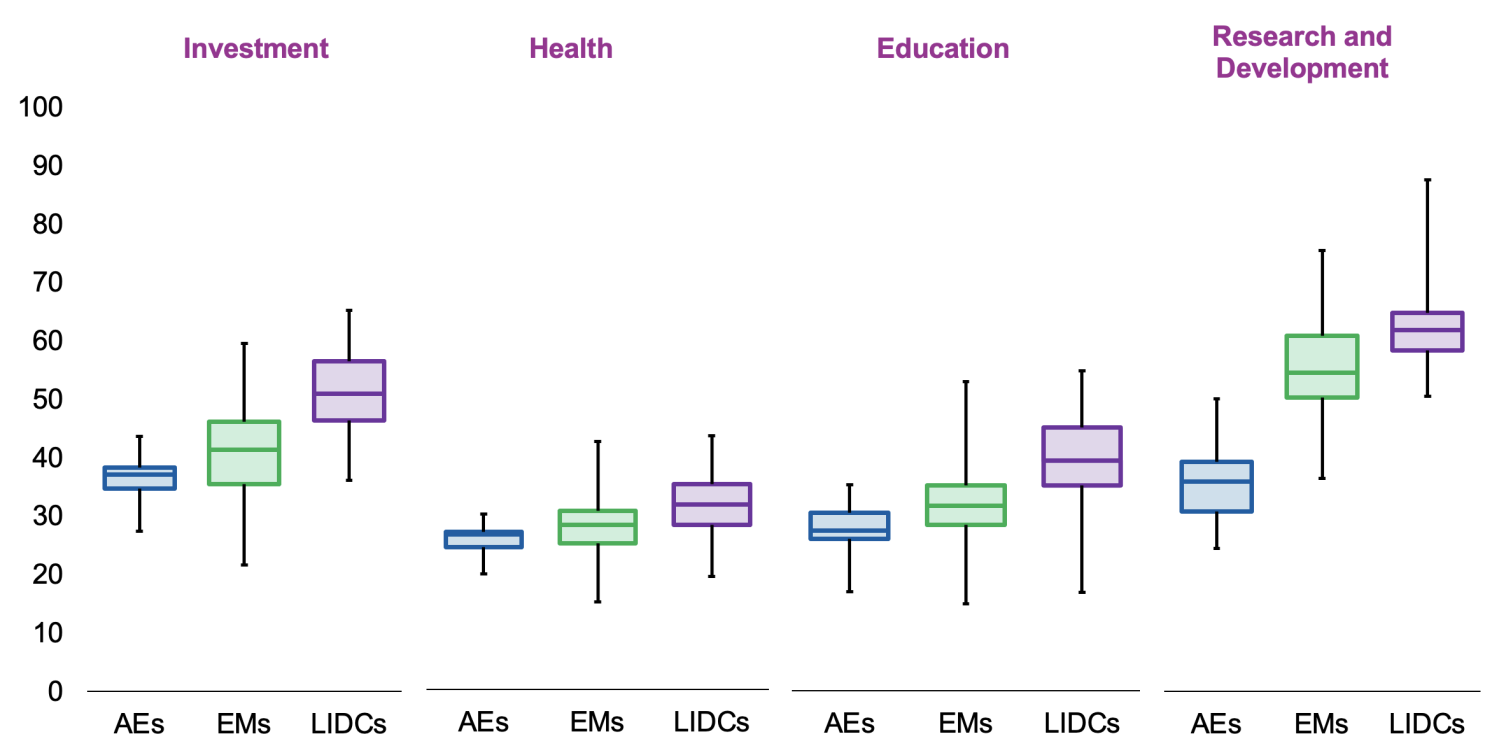

Our newly developed data for 174 countries illustrates that almost all have substantial room for improvement in public spending efficiency. Utilizing comprehensive research (e.g., Apeti et al. 2023, Herrera et al. 2025), we assess how far countries are from the production possibilities frontier—representing optimal outcomes in infrastructure, health, education, and R&D investment. Importantly, our estimates not only vary over time but also consider structural differences across nations, statistical variances, and uncertainties regarding outcome variables.

The dataset highlights that global efficiency gaps are estimated at 30-40% and are especially pronounced in infrastructure and R&D sectors (Figure 1). These gaps have significantly narrowed over the past four decades, reflecting global improvements in life expectancy, technological progress, and broadened access to fundamental infrastructure in low-income nations.

Figure 1 Public spending efficiency gaps (percent)

Notes: This figure illustrates the efficiency gaps measuring the distance to the spending efficiency frontier, ranging from 0 (fully efficient) to 100 (fully inefficient). The data showcases averages from 1980 to 2023 with boxes indicating medians and interquartile ranges (25th-75th percentiles), while whiskers denote minimum and maximum values. AEs = advanced economies, EMs = emerging market economies, LIDCs = low-income developing countries.

Output Gains from Reforms

A wealth of literature highlights the contributions of public spending allocation and efficiency to economic growth. According to standard growth models, investments in physical and human capital advance the economy’s productive potential, while public R&D expenditures enrich the knowledge pool that firms leverage for innovation (Barro and Sala-i-Martin 2004). Enhanced public investment contributes significantly to the capital stock (Gupta et al. 2014, Presbitero et al. 2016).

Our research adds to this body of work by examining two significant dimensions. First, we evaluate how the composition of public spending influences economic activity under the condition that overall spending remains constant. Second, we investigate how economic impacts differ across countries and over time, relying on our newly acquired efficiency estimates.

Evidence from approximately 700 instances of substantial public spending reallocations across 155 countries indicates that output experiences significant boosts in the short to medium term. Major reallocations towards public investment lead to approximately a 4% output increase after ten years, while reallocating to public health and R&D generates 3% output growth over the same period. Notably, these gains begin to emerge within the initial five years and strengthen as time progresses.

Our simulations of an endogenous growth model clearly demonstrate the potential long-term benefits and the mechanisms at play. Public infrastructure complements private capital and labor (as noted in Traum and Yang 2015), while investments in human capital enrich the productivity of time spent in education, thereby accelerating skill development. Moreover, public R&D funding expands the available innovation stock for firms to adopt, with a gradual diffusion of technology occurring as firms invest in its utilization (as suggested in Anzoategui et al. 2019). Our model incorporates inefficiencies in public investment, human capital, and R&D by recognizing that some public expenditures can be wasted instead of contributing to capital and knowledge accumulation (as discussed in Berg et al. 2019).

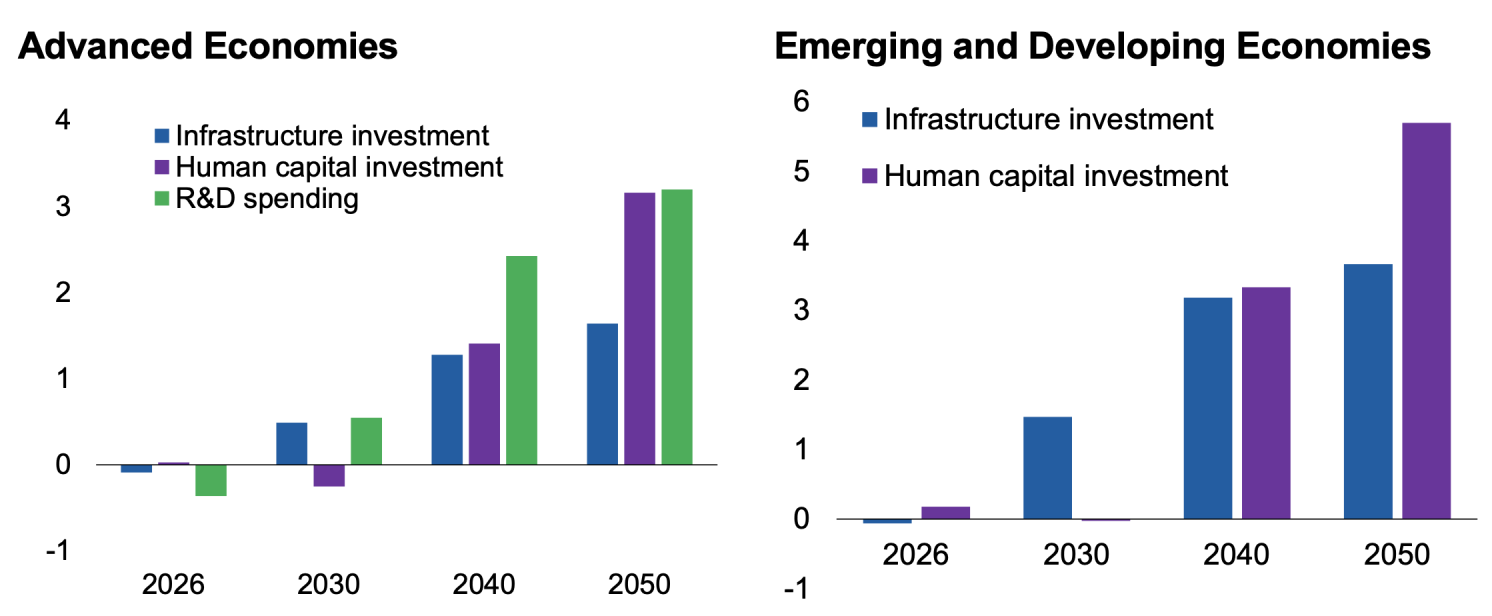

Figure 2 Long-term output gains from reallocating spending (percent)

Notes: The bars reflect long-term output gains from a continuous increase of 1% of GDP in the listed expenditure categories for 2025, financed through a reduction in public consumption.

The findings indicate that reallocating 1% of GDP from government consumption (e.g., administrative expenditures) to public investment in human capital—such as improving national curricula and equipping educational institutions—can boost output by 3% in advanced economies and 6% in emerging markets in the long term (Figure 2). The more significant gains for emerging markets result from their relatively low initial levels of human capital, leading to a higher return on investment. These insights are further supported by de La Maisonneuve et al. (2024), emphasizing that enhancements in early childhood education and increased funding for low-investment countries could yield substantial productivity benefits over the long term as the next generation enters the workforce.

Redirecting funds to infrastructure investments yields long-term output gains of 1.5% in advanced economies and 3.5% in emerging markets. Additionally, reallocating public funds toward R&D by 1% of GDP could increase output by 3% in advanced economies over time.

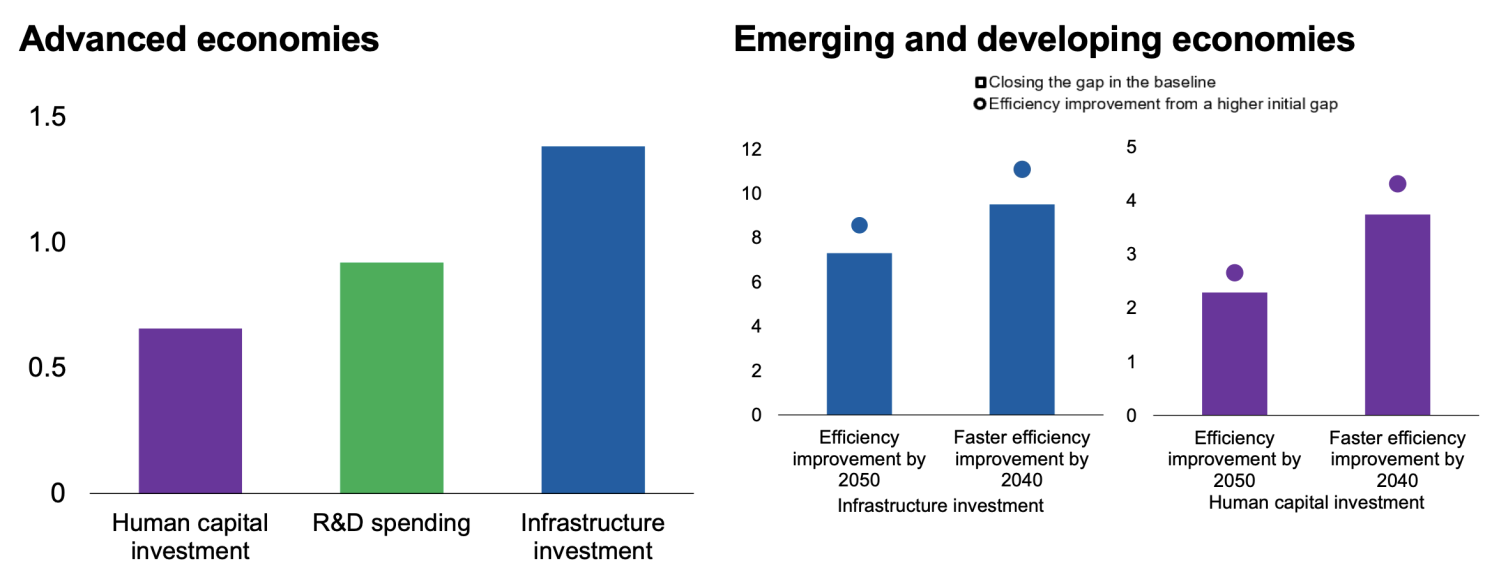

Importantly, addressing spending efficiency gaps can further enhance output effects, with potential increases of 1.5% in advanced economies and 2.5-7.5% in emerging markets, as more public funding translates into productive assets and scientific advancements (Figure 3). Should improvements in spending efficiency occur more rapidly, output gains could be up to 2% greater.

Supplementary policy measures could amplify these benefits. In advanced economies, combining investments in both human capital and R&D yields greater advantages than focusing solely on one aspect, due to the synergy between innovation and skill development. In emerging markets, a joint approach between infrastructure and human capital investment optimizes both immediate and prolonged benefits.

Figure 3 Long-term output gains from improving spending efficiency (percent)

Notes: The bars depict long-term output gains from gradually closing gaps in spending efficiency either by 2050 (left panel) or by 2040 or 2050, as indicated along the horizontal axis (right panel). The circles illustrate the potentially larger gains achievable for countries operating from a higher initial efficiency gap.

For references, see the original post.