Welcome to our analysis of the recent reactions surrounding the Federal Reserve’s repo facility activity as the year drew to a close. There’s been a flurry of speculation and alarming commentary regarding these financial maneuvers, yet it’s crucial to sort fact from fiction. Let’s delve into the context and implications of this situation.

Yves here. I find it puzzling to highlight the recent year-end activity in the Fed’s repo facility, especially considering past situations—most notoriously during the 2019 repo panic—where commentators have reacted overwhelmingly to what turned out to be minor issues. This instance appears to be no different.

Numerous readers reached out, pointing to sensational claims from so-called experts about the spikes in repo facility usage in late December, interpreting them as covert bank bailouts. We possess evidence from our prior communications that this panic was greatly exaggerated. Initially, we hesitated to counter this perspective, knowing that attempting to debunk such claims can often inadvertently reaffirm the original message.

Wolf provides pertinent data, echoing our viewpoint that year-end typically results in constrained liquidity. Many institutional investors aim to close their books by December 15.

Furthermore, the Fed has revised its approach to managing short-term liquidity. In my observation, this has exacerbated issues during financial crunches. Following the crisis, the Fed shifted from primarily handling short-term liquidity through daily open market operations to offering interest on reserves—an unmerited boon to banks. This strategy works well in loose monetary conditions but falters during tightening cycles. Notably, three months prior to the 2019 panic, the New York Fed lost its two top traders on the money desk, suggesting a potential reduction in the unit’s significance. My impression, based on subsequent developments, is that the Fed has struggled to effectively utilize the repo facility as an alternative to direct interventions by the money desk. Additionally, the downgrade of the once-critical New York Fed money desk may have resulted in a loss of market intelligence.

During this year-end period, the CME significantly increased margin requirements for certain metals. It’s easy to surmise that some banks may have opted to hoard liquidity in anticipation of hedge funds, caught off guard by these changes, significantly drawing down their borrowing lines to fulfill margin calls.

We consulted derivatives expert Satyajit Das for his views at the time. He responded:

1. Money market conditions are volatile largely due to the year-end and the Treasury’s reliance on T-bills for funding, compounded by uncertainties surrounding the Fed and interest rates. Bank funding costs have escalated for these reasons. Additional concerns include potential hidden problems lurking within the system—those “credit cockroaches,” as JP Morgan’s CEO Dimon put it—which could lead to more significant credit losses than anticipated, particularly affecting hedge funds and commodity businesses due to increased margin calls driven by price volatility.

2. I recognize that the Fed has intensified its repo operations to manage short-term fluctuations, which is part of its usual functions. The amounts discussed in the article are relatively minor in the grand scheme of things.

By Wolf Richter, editor at Wolf Street. Originally published at Wolf Street

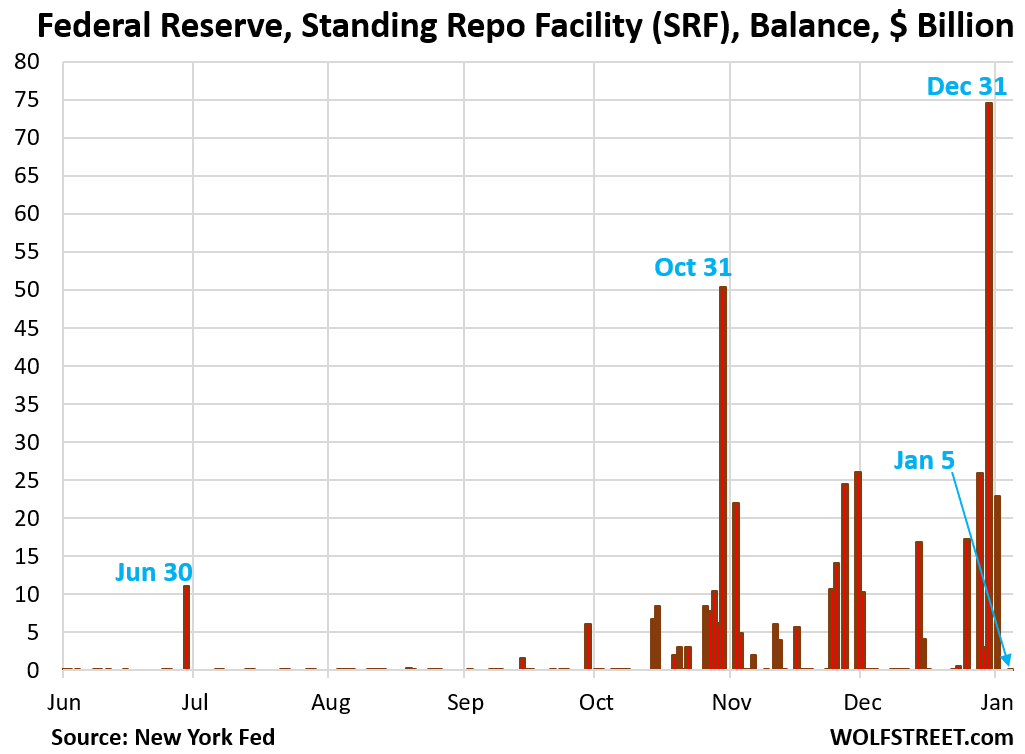

Recently, the balance at the Fed’s Standing Repo Facility (SRF) returned to zero, with all repos unwound as of today, accompanied by no new repos at the two auctions, as anticipated.

The SRF had surged to $75 billion on December 31 due to year-end liquidity adjustments, a jump from zero before Christmas. This spike was a substantial contributor to the $104 billion increase in the Fed’s weekly balance sheet as of the close on December 31.

However, this anomaly has since entirely unwound. The Fed’s forthcoming weekly balance sheet, set to release on Thursday, is expected to display a significant reduction in overall assets.

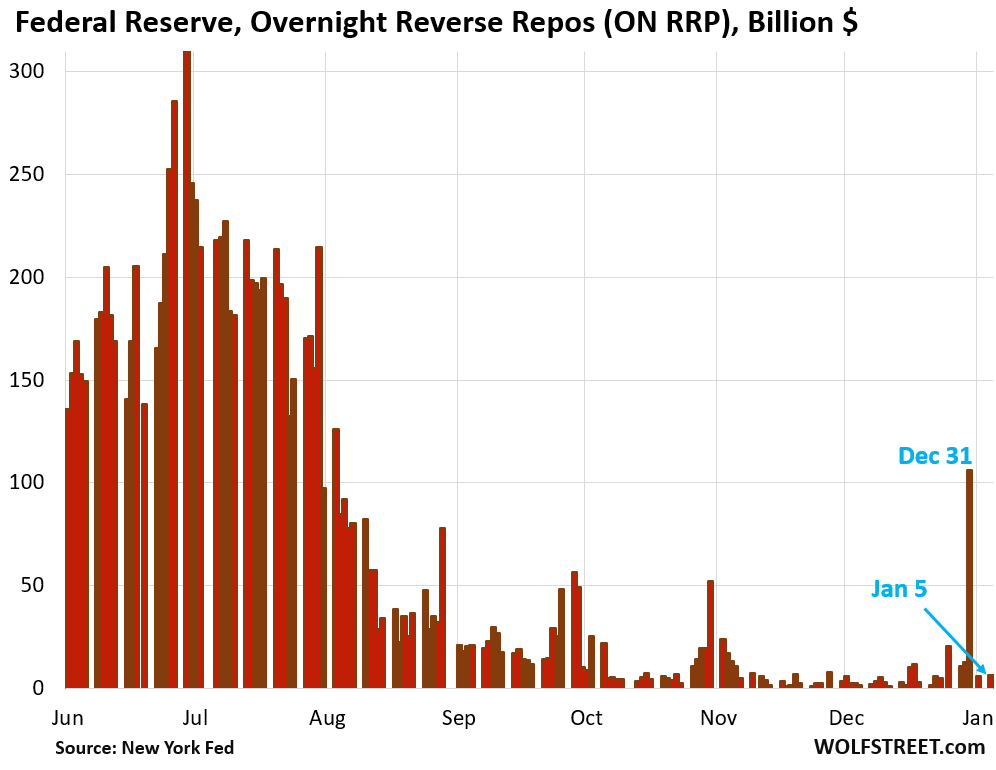

As the year came to a close, significant amounts of liquidity shifted within markets, creating tight spots in certain areas and producing spikes in repo market rates, such as SOFR, while also leading to excess liquidity in others, manifested in increased balances at the Fed’s overnight reverse repo facility (ON RRPs), which effectively drain liquidity from the markets.

The tight spots were evident as repo market rates surged, notably reflected in SOFR, which skyrocketed to 4.0% on December 31. On that same day, SOFR—a median calculation for the day’s rates—climbed to 3.87%.

This rise in repo rates created favorable conditions for banks, allowing them to secure $75 billion from the SRF on December 31 at 3.75% and lend at higher rates in the repo market throughout the holiday until Friday morning.

By January 2, as repo market rates declined—with the peak down to 3.87% and SOFR settling at 3.75%—this profit opportunity evaporated. Consequently, banks unwound most of their repos at the SRF on Friday and cleared the remainder today, returning the balance to zero.

While the Fed’s weekly balance sheet, which reflects figures as of the close on Wednesday, recorded the $75 billion spike at the SRF, that surge primarily influenced the previously mentioned $104 billion increase in the Fed’s total assets released on Friday.

Now, the Fed has reclaimed its $75 billion, and those involved have received their collateral back. This amount has been completely unwound and is no longer reflected in the Fed’s assets.

The excess liquidity that also emerged in other market sectors on December 31 was evident in the Fed’s overnight reverse repo facility (ON RRPs). This balance has also been nearly fully unwound.

This excess liquidity was observed as the ON RRP balance spiked to $106 billion on December 31.

ON RRPs mostly consist of excess cash deposited by money market funds at the Fed, which essentially lends their surplus cash to the Fed at an interest rate of 3.5%. These funds are a liability on the Fed’s balance sheet, as the Fed owes them this cash.

By January 2, the ON RRP balance plummeted to $6 billion from $106 billion on December 31, where it stayed today. This situation has also normalized as expected.

These two Fed facilities—the SRF and ON RRPs—are integral to the Fed’s strategy of controlling short-term interest rates, ensuring they remain aligned with its monetary policy rates, currently set between 3.5% and 3.75%.

The SRF rate serves as a ceiling rate—one of the tools employed to prevent overnight rates from exceeding the Fed’s upper limit of 3.75%.

Conversely, the ON RRP rate acts as a floor rate, ensuring short-term rates don’t fall below the Fed’s lower boundary of 3.5%.

It’s essential to note that the counterparties for these two facilities differ, which means the rates impact various market segments: The SRF partners with 43 large banks, broker-dealers, and a credit union, while the ON RRP counterparties are primarily money market funds.

After three years of quantitative tightening (QT) that removed $2.43 trillion in liquidity from markets, we can expect these types of brief liquidity fluctuations to become more common on significant dates throughout the year, such as year-end, quarter-end, month-end, and particularly during tax periods, around April 15.