Recent developments in the European Union’s relationship with China have put the spotlight on the EU’s strategy to “derisk” its economic ties with Beijing. As Ursula von der Leyen and her allies confront this complex issue, it’s evident they possess far less leverage than their Chinese counterparts. This imbalance is becoming increasingly apparent:

“European Union is privately warning that there’s little it can do in the near term to compel China to ease export controls on critical rare earths, a move that’s caused major disruptions for Europe’s industry, including auto and defense manufacturers.” https://t.co/aWk1HA0N1H

— Shehzad Qazi (@shehzadhqazi) November 6, 2025

While China has begun to lift some export restrictions on critical minerals for the U.S., it has not fully abided by the more lenient measures that the Trump administration anticipated. Furthermore, it remains uncertain if the EU will receive similar concessions. According to Bloomberg:

While the EU will benefit from an agreement between U.S. President Donald Trump and China’s Xi Jinping to pause stringent new export controls China announced in October, earlier restrictions imposed in April will remain, said the people.

Discussions between Chinese and EU officials in recent days have failed to move the needle, said the people, who spoke on the condition of anonymity.

…China and the EU have been discussing the issuance of general licenses, which would allow for repeated shipments of rare earths over a period of time to pre-approved buyers, the people said. But they cautioned such a solution would take time and the EU would ultimately remain at the whim of decisions taken in Beijing.

It appears Brussels may need to make significant concessions before Beijing is willing to negotiate. This situation is complicated by ongoing tensions, such as the recent Dutch acquisition of chipmaker Nexperia, which further strains relations between the EU and China, especially in light of Taiwan’s growing prominence within EU discussions.

This predicament underscores the inadequacies of the European political elite led by Ursula. It raises the question of how Europe remains so vulnerable to China’s economic machinations. Nearly three years ago, at the Mercator Institute for China Studies and the European Policy Centre, Ursula launched the initiative to reduce reliance on China—a mission that appears to have faltered.

In itself, the strategy of “derisking” should hold merit, especially if the leaders possess a coherent execution plan. Regrettably, so far, EU leaders have failed to establish a practical approach. Instead, the derisking strategy proposed lacked depth and direction, simply aligning the bloc with Washington without contingencies for potential fallout.

As it turns out, not only has the EU struggled to lessen its dependence on China, but it has simultaneously heightened its reliance on the U.S.

The rare earth situation illustrates the EU’s lack of strategic direction and serves as a warning for the U.S., which is currently attempting an “Operation Warp Speed” 2.0 to reduce its reliance on Chinese rare earth processing. This ambition, while laudable, fails to account for other critical dependencies that will continue to empower Beijing in future economic conflicts.

Derisking Failure

Ursula began promoting the derisking initiative back in March 2023, yet the EU didn’t enact any critical minerals legislation until more than a year later. The European Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA) was adopted in March 2024, while the EU’s Net-Zero Industry Act (NZIA) took effect on June 29, 2024.

The NZIA aims for Europe to produce at least 40% of its annual net-zero technology deployment needs domestically by 2030, along with a 15% global share in net-zero tech manufacturing by 2040.

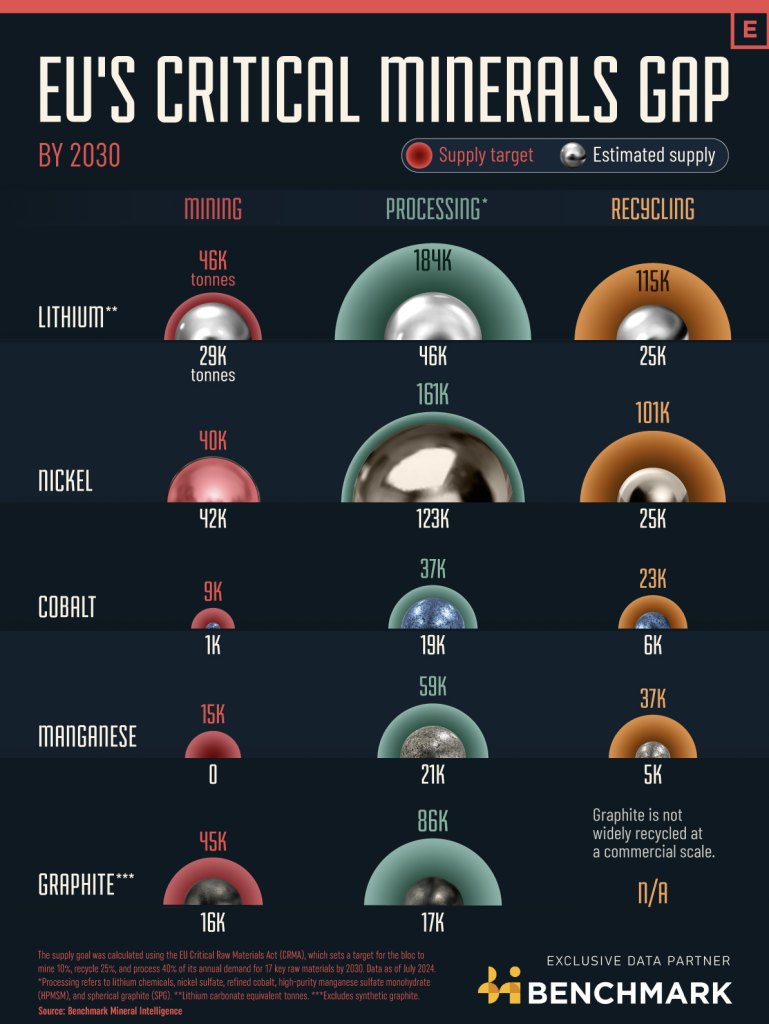

Conversely, the CRMA targets the following production goals by 2030:

- At least 10% of the EU’s annual consumption from domestic extraction

- At least 40% from domestic processing

- At least 25% from domestic recycling

- No more than 65% of the EU’s consumption from a single foreign country

The progress has been lackluster, and continual EU provocation towards China exacerbates the situation.

Regarding the NZIA, a European Parliament report suggests that the EU is actually losing ground in the global net-zero tech market:

While the roll-out of clean technologies is increasing in the EU, its global market share is falling and manufacturing is lagging behind. This is due to a combination of factors, such as high energy prices, dependency on imported raw materials and key components, skills shortages, and fierce international competition, bolstered by robust public support policies adopted by the EU’s main global competitors, such as China and the United States.

It’s worth considering the strategic missteps made by Ursula and her administration. By distancing themselves from Russian energy, they have inadvertently made EU clean technology less competitive. Now, in their bid to compete with China, they have further compromised access to the rare earth elements essential for these technologies.

How is the initiative to secure alternative sources of critical minerals progressing? Unsurprisingly, poorly.

The CRMA has enabled the European Commission to sidestep some environmental regulations and public resistance on specific projects long in planning, but significant hurdles remain.

A prominent obstacle is the lack of governmental support for mining operations. Since these projects necessitate substantial time and investment, and face challenges from dominant Chinese firms, they often struggle to attract investment.

Although deposits exist in Norway, Sweden, and Greenland, there are currently no operational rare earth mines within EU borders. The average timeline from discovery to production is around 15.3 years.

EU research indicates a potential for meeting up to 30% of demand through increased recycling by 2030, yet current recycling rates remain below 1%. Industry experts widely believe that the CRMA’s 2030 goals are unachievable.

The following image highlights the substantial gaps still needing to be addressed:

Despite little progress and the looming threat of being cut off by China, EU officials have escalated their economic tensions with Beijing. European media often present the bloc as a passive entity in the ongoing U.S.-China economic conflicts, but this depiction is misguided.

China Briefing recently published a comprehensive analysis detailing how Brussels has intensified the trade war since the 2024 EU elections. This includes ongoing pressure from European leaders for China to diminish its relationship with Russia over the Ukraine crisis. The EU has even proposed sanctions on Chinese companies purchasing Russian oil.

Moreover, the EU has imposed tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles, targeted platforms like Shein and Temu, attempted to halt a BYD factory in Hungary, fined TikTok, and controversially banned its DeepSeek AI. The Dutch also attempted to seize semiconductor manufacturer Nexperia, although they seem to be backpedaling on this initiative.

This aggressive posture is no surprise, as early this year, European Trade Commissioner Maroš Šefčovič publicly stated that the EU intends to collaborate with the U.S. in confronting China economically.

Additionally, the EU and its individual nations have increasingly shown support for Taiwan, which Beijing considers a red line. NATO countries even transited warships through the Taiwan Strait despite dire warnings from China. The European Parliament’s invitation to Taiwan’s second-highest leader is seen as yet another provocation—a clear signal that they are daring China to sever their access to crucial rare earth materials.

Through all of this, the EU has not managed to organize its affairs effectively.

A recent report from the Financial Times echoes the dire circumstances, reminiscent of the bloc’s hasty decision to reduce its reliance on Russian gas. The FT suggests that Brussels is now “racing to develop stockpiling strategies” and acknowledges that the EU has “finally woken up.”

On October 25, Ursula announced a joint purchasing and stockpiling initiative (a detailed proposal is expected soon). However, it’s difficult to see how this will succeed when, in certain instances, the primary supplier has effectively cut off the EU. Erik Eschen, CEO of permanent magnet manufacturer VAC Group, stated to the FT that it’s “too late” for stockpiling, as governments would struggle to acquire the necessary materials from China.

This situation illustrates the lack of foresight by Ursula and her colleagues. They unveiled a derisking strategy two years ago but accomplished little except fueling tensions with China. When Beijing responds, they find themselves caught unprepared.

Ironically, this same leadership has been asserting for three years that Russia is poorly equipped for conflict, yet now they are confronted with potential shortages as they seek to rearm for a confrontation they seem to anticipate with Russia. The FT notes, “Beijing’s restrictions complicate securing minerals needed to produce military equipment as the bloc aims to bolster its defense capabilities.” This irony is underscored by the current situation.

Will the U.S. Fare Any Better?

Perhaps. If Washington commits substantial resources, it might succeed. The Institute for Progress and Employ America recently released a report advocating for just that, arguing, “We have everything at our disposal to tackle the threat. America and its partners possess the mineral resources necessary for a self-sufficient supply chain. Only a non-traditional approach can address the market challenges.” They propose four essential steps:

-

Foster competition and innovation.

-

Collaborate with international partners to create resilient supply chains beyond China.

-

Revise permitting processes to restore predictability.

-

Ensure that national security-based U.S. technology restrictions remain non-negotiable.

Trump is now rapidly signing rare earth agreements with willing partners, including Australia, Malaysia, Thailand, Japan, and Central Asian nations. However, these arrangements are minimal compared to the vast challenges ahead, particularly concerning processing and ensuring financial viability. As RFE/RL noted, “It’s China’s dominance in the processing of rare earths that poses a more significant hurdle than the supply itself,” according to William Courtney, a former U.S. ambassador to Kazakhstan and adjunct senior fellow at the Rand Corporation.

Although the Institute for Progress and Employ America claims that the U.S. is equipped for self-reliance, one must question this assertion.

Isolating and refining rare earths is not as straightforward as merely injecting money into the issue. As Rare Earth Exchange highlights:

Separating and refining rare earth elements (REEs) at an industrial scale is far more complex than it sounds. Many companies outside of China boast innovative separation technologies, but few have achieved significant success at scale. Observers note an uneven knowledge distribution: only a handful of seasoned experts in REE separation are present in the U.S., Europe, or Japan, whereas China has thousands of experienced engineers.

Chinese authorities meticulously guard this expertise—rare earth companies are required to register technical specialists, and passports may be confiscated to prevent sensitive information from leaving the country. This practice has been in place long before President Trump’s trade war commenced. The result is a daunting challenge for Western nations to catch up with China’s over 90% share in rare earth processing.

There’s a reason it took China decades and billions of dollars to dominate the rare earth supply chain while Western powers watched idly.

Where Are the Other Operation Warp Speeds?

While rare earths are currently in focus, they represent just one facet of China’s significant influence on essential products for the U.S. and Europe. Even if the ‘West’ were to ramp up rare earth production within a year, where is the Operation Warp Speed 3.0 for pharmaceuticals, 4.0 for lithium-ion batteries, and 5.0 for advanced semiconductors?

Consider pharmaceuticals as a case in point. The U.S. may source most of its drugs from the EU and India, but where do these countries obtain their active ingredients? China. A previous post highlighted that:

…prior to the relaxation of its zero-Covid policy, shortages of medicines in the EU—ranging from children’s fever reducers to antibiotics—were already apparent. Approximately 80% of active pharmaceutical ingredients used in Europe, and about 40% of finished medicines sold there, come from China or India. Escalating EU-China tensions could trigger a resurgence in these shortages:

China is a key producer of many essential unbranded medications frequently used in hospitals. Antibiotics, in particular, have seen increased outsourcing to Asian manufacturers, positioning China as a dominant force in this market.

Based on data from 2021, China supplied roughly 95% of vitamin B1 and its derivatives to the EU. Over 96% of heterocyclic compounds essential for numerous antibiotics were imported from China as well. Dependencies on other critical substances, like chloramphenicol, have also surged, reaching over 98%. This substance is vital for treating serious infections resistant to other antibiotics.

Even when manufacturing occurs in Western nations or India, these operations often rely on raw materials sourced from China. For instance, India imports about 70% of APIs from China, including those crucial for antibiotics and medications for diabetes and heart diseases. In fact, China can produce APIs 20-30 percent cheaper than India due to its availability of low-cost raw materials.

As reported by the New York Times, a piece on a closed generic drug plant in Louisiana illustrates the lack of financial motivation for U.S.-based production when it’s much cheaper to rely on Chinese ingredients produced with low-cost labor in India.

The consequences of decades spent aligning global markets with financial incentives are now manifesting.