In recent times, the U.S. war on drugs has increasingly come under scrutiny and skepticism. Historically, it has appeared more as a vehicle for funding dubious foreign initiatives while creating a façade of domestic concern. The current alarming phase—using drug trafficking as justification for regime change in Venezuela and publicizing extrajudicial killings—underscores that the subtle distinctions of this conflict often escalate into something far more severe.

This article delves into the convoluted history of the U.S. approach to drug addiction, rife with contradictions and unsettling tales. Despite the missteps in current policies, there remains a crucial need to address the underlying issues—although not through the means currently employed by the U.S.:

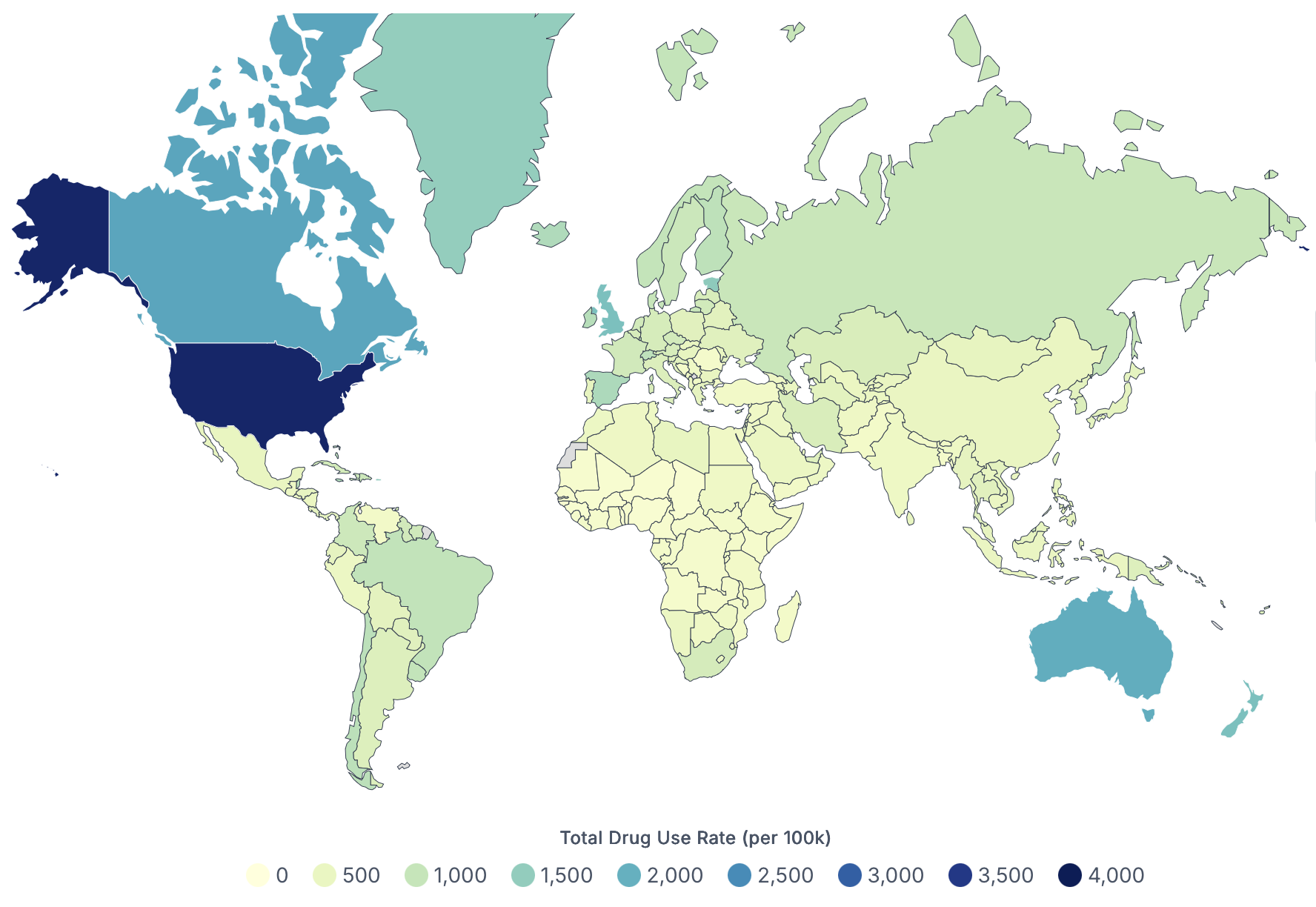

The chart from World Population Review is interactive, providing an engaging visual representation of each country’s drug use statistics per 100,000 people. You can view these details by hovering over each country.

Another crucial point, often overlooked, is that merely targeting foreign supply chains fails to address domestic drug consumption. Former ambassador Chas Freeman highlighted that the two instances where large-scale addiction was effectively curtailed—China during the Opium Wars and in the U.S. post-Civil War—involved the forcible rehabilitation of addicts and targeting domestic distribution networks. However, such drastic measures are impractical in today’s society, which would necessitate extensive support services to assist those recovering from addiction. With job markets becoming increasingly specialized, the challenge of integrating former addicts back into the workforce only compounds the issue. While solutions could be pursued, they would require a commitment to social services that the U.S. has yet to fully embrace.

Written by Greg Grandin. Originally published on TomDispatch.

Presently, Donald Trump effectively runs a shadow state, more akin to a death squad than a government.

Many dismissed his early second-term claim that the Gulf of Mexico would be referred to as the Gulf of America as a trivial act of bravado. However, it has since precipitated a continuous bloodshed in the Caribbean Sea. The Pentagon has obliterated 18 fast boats in this region without presenting firm evidence that any were engaged in drug trafficking. Surveillance footage has been circulated showing these strikes—a grim display of targeted killings—where vessels disappear, along with their human cargo, be they drug smugglers, fishermen, or migrants. Reports indicate that at least 64 lives have been lost in these assaults.

The frequency of these attacks has surged. Initially, strikes occurred every eight to ten days in September, ramping up to one every two days by early October. By mid-October, attacks transpired daily, including multiple strikes on October 27 alone. It seems that bloodshed breeds more bloodshed.

These operations have spread beyond the Caribbean, expanding to the Pacific coasts of Colombia and Peru.

Trump’s motives for such violence may stem from a thirst for power or a desire to provoke conflict with Venezuela. Some suggest these actions serve as distractions from the many criminal charges and accusations of corruption that shadow his presidency. Moreover, the ruthless killing of Latin Americans plays into the hands of his base, who, stirred by culture wars led by figures like Vice President JD Vance, look for scapegoats for the opioid crisis overwhelming rural white communities in America.

The criminal acts, which Trump insists are part of a broader war against cartels and traffickers, represent a shocking display of violence. They reflect the chilling cruelty espoused by Vance, who has mocked the idea of killing fishermen and claimed indifferently that legality matters little in these contexts. Trump has similarly disregarded the need for congressional approval for military strikes, stating, “I think we’re just gonna kill people. Okay? We’re gonna kill them. They’re gonna be, like, dead.”

Yet, it’s critical to recognize that Trump’s actions are enabled by longstanding policies and institutions established by his predecessors. His administration is not merely escalating the drug war but heightening its existing atrocities.

What follows is a brief exploration of how we arrived at a point where a president can order repeated killings of civilians, share videos of these acts, and encounter little more than indifference or complacency from many lawmakers, journalists, and legal experts (with Rand Paul being a noted exception).

A Brief History of the Longest War

Richard Nixon (1969-1974) has the dubious distinction of being the first American president to escalate the drug war.

On June 17, 1971, as the Vietnam War was still settled in turmoil, Nixon announced an “all-out offensive” on drugs. Although he avoided the term “war on drugs,” the phrase was rapidly adopted in the following days across numerous news outlets, hinting at orchestration from the White House.

This call for a drug crackdown came in response to a sensational article from the New York Times, “G.I. Heroin Addiction Epidemic in Vietnam,” highlighting a staggering number of U.S. soldiers suffering from heroin addiction, with some reports indicating that more than half of certain units were using the drug.

Faced with inquiries not only about the end of the Vietnam War but also about addressing the rising addiction among military personnel, Nixon initiated what could be viewed as a second act to Vietnam—a global military expansion now focused on combating marijuana and heroin rather than communism.

In 1973, following the last U.S. combat soldier’s departure from Vietnam, Nixon established the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). The agency’s inaugural significant operation in Mexico mirrored the strategies employed in Vietnam. U.S. agents collaborated with local law enforcement to execute militarized sweeps and aerial fumigation campaigns starting in 1975. These operations targeted rural marijuana and opium producers, resulting in a nightmare of extrajudicial killings and torture of predominantly impoverished farmers. Rather than mitigating drug production, the campaign resulted in its centralization within a few powerful paramilitary organizations, eventually evolving into what we now identify as drug cartels. Historian Adela Cedillo noted that instead of decreasing production, this militarized approach significantly contributed to the rise of organized crime.

Thus, the first fully militarized front in the War on Drugs inadvertently facilitated the creation of the very cartels that the renewed war now seeks to combat.

Gerald Ford (1974-1977) faced mounting pressure from Congress, particularly from New York representative Charles Rangel, and opted for a “supply-side” approach that targeted drug production directly—alongside reducing demand in the U.S. Historically significant sources of heroin for the U.S. included countries in Southeast Asia, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Iran, but Mexican production began to rise in response to the demands of veterans returning from Vietnam, generating over 85% of the heroin entering America by the mid-1970s. A White House aide warned Ford of the troubling developments in Mexico in preparation for a meeting with Rangel.

Ford escalated operations by the DEA throughout Latin America.

Jimmy Carter (1977-1981) took a more compassionate route, advocating for the decriminalization of marijuana for personal use. However, despite his emphasis on treatment rather than punishment, the DEA’s international operations expanded, with the agency soon managing numerous offices across Latin America.

Ronald Reagan (1981-1989) ushered in a surreal period for drug policy, intertwining rightwing politics deeply with illicit drug trade.

To understand this evolution, one must go back further in time. The intersection of rightwing politics and the drug trade began post-World War II, when U.S. intelligence relied on crime boss Lucky Luciano’s international narcotics syndicate to execute covert anti-communist operations in Italy. Following the Cuban Revolution in 1959, traffickers migrated, contributing to drug trafficking elsewhere in Latin America and the U.S., often aligning with anti-communist political objectives.

Simultaneously, the CIA deployed these gangster exiles to destabilize Fidel Castro’s regime, all while running its own airline, Air America, to support clandestine initiatives in Southeast Asia through opium smuggling. The FBI similarly exploited drug-related charges to disrupt and discredit political dissenters, notably in cases like that of Martin Sostre, a Black activist wrongfully accused of drug dealings.

Nixon’s establishment of the DEA unified these disparate threads, as its agents collaborated closely with both the FBI and CIA. Following the Vietnam War’s conclusion, as Congress sought to curb the CIA’s reach, it resorted to leveraging the DEA’s expansive network to continue covert operations.

When Reagan assumed office, coca production was rampant in Latin America, and a curious dynamic emerged: the CIA assisted repressive governments involved in coca production while the DEA endeavored to curtail that same production. An early instance of this was in 1971 when the CIA helped orchestrate a coup in Bolivia that would result in the very “cocaine colonels” who received U.S. funds to combat drug production while simultaneously facilitating its growth for export. President Carter’s funding cuts to Bolivia in 1980 were later reinstated by Reagan.

The rise of Chilean dictator General Augusto Pinochet mirrored this dynamic. His regime, aided by the CIA, used warfare against socialism in part as a guise for drug policy enforcement, often torturing political opponents and drug traffickers alike. Many tied to his administration engaged in drug trafficking, with Pinochet’s own family reportedly profiting enormously from cocaine sales to Europe.

Upon taking office, Reagan escalated the drug war, drawing tighter connections between cocaine and rightwing political agenda. Notably, the Medellín cartel’s monetary support for Reagan’s campaign against Nicaragua’s Sandinista government exemplified this entanglement. The complexities of these ties have often been described as part of a “covert netherworld,” detailed in the work of investigative journalists.

George H.W. Bush (1989-1993) employed theatrical tactics akin to those of Trump, enhancing public awareness of his drug policies. A striking moment occurred when he showcased a bust of crack cocaine during a live televised event, using the high-profile arrest of a low-level drug dealer as fodder for further policies. This event, however, resulted in a long prison sentence for the dealer, illustrating the political theater surrounding drug enforcement.

Bush significantly bolstered military and intelligence operations aimed at drug interdiction, particularly in the Caribbean and Andes. This period became known for its representation in media such as *Miami Vice*, where attempts to thwart cocaine smuggling merely shifted transportation routes through Central America and Mexico. One of Bush’s hallmark strategies involved *Operation Just Cause,* where he sent thousands of troops to arrest Panamanian leader Manuel Noriega on drug trafficking charges, despite the fact that Noriega had previously served as a CIA asset.

Bill Clinton (1993-2001) further intensified the tough-on-drugs stance established by his Republican predecessor, maintaining mandatory minimum sentences and a growing prison population filled with drug offenders.

As his presidency drew to a close, Clinton introduced Plan Colombia, committing additional billions toward drug interdiction efforts with a privatization twist. The U.S. government outsourced operations to contractors like DynCorp, which undertook aerial fumigation. This initiative led to catastrophic ecological impacts and a rising number of civilian casualties, with coca cultivation increasing significantly during this time.

George W. Bush (2001–2009) escalated the conflict yet again, advocating for heightened funding toward domestic and international drug operations. He also encouraged Mexico’s president, Felipe Calderón, to launch a brutal crackdown on drug cartels that ultimately resulted in tens of thousands of deaths.

Linking the post-9/11 Global War on Terror with the war on drugs, Bush asserted that “Trafficking of drugs finances the world of terror.”

Barack Obama (2009–2017) took a more compassionate approach, emphasizing treatment over incarceration, but continued the financial support for operations like Plan Colombia. He largely overlooked the 2009 report from former Latin American presidents advocating for drug decriminalization.

Donald Trump (2017–2021) expanded investments in militarized drug operations, suggesting extreme measures such as the death penalty for drug dealers. He even floated the idea of using missiles against drug facilities in Mexico without making U.S. involvement known.

In May 2017, under his leadership, a tragic incident occurred when DEA agents, working with Honduran officials, opened fire on a civilian boat carrying multiple passengers, resulting in several deaths. A subsequent investigation bore no repercussions for the U.S. personnel involved.

Joe Biden (2021–2025) indicated support for de-escalation and reduced funding for certain operations but remained committed to continued support of the DEA and military efforts in Latin America.

Donald Trump (2025-?) has opened a new chapter in his domestic drug war, targeting cartel activities in New England. Reports from the DEA suggest major arrests in Massachusetts and New Hampshire, primarily apprehending low-level offenders rather than high-ranking cartel members.

Trump asserts that the war on drugs is not merely a metaphorical conflict; rather, he believes it grants him exceptional wartime powers—including the capacity to bomb targets in Mexico or launch attacks on Venezuela.

Given this intricate history, what rationale could there be for believing this war could yield a favorable outcome, or even conclude in any meaningful way?

Copyright 2025 Greg Grandin