A recent analysis sheds light on the critical interplay between government funding and private innovation in the United States. This exploration stems from Marianna Mazzucato’s influential work, *The Entrepreneurial State*, revealing how public investment has been pivotal in driving innovation. The following study delves deeper, highlighting that patents funded by the government yet privately owned tend to yield significant productivity gains.

By Andrea Gazzani, Senior Economist Bank Of Italy, Joseba Martinez, Assistant Professor of Economics London Business School, Filippo Natoli, Senior Economist Bank Of Italy, and Paolo Surico, Professor of Economics London Business School. Originally published at VoxEU

The United States has long been a leader in global innovation, driven by a robust system that merges public funding with private enterprise. Nonetheless, this model faces significant challenges. An analysis using newly digitized patent data since 1950 reveals that while publicly funded and privately owned patents constitute merely 2% of all US patents, they are responsible for approximately 20% of fluctuations in productivity and GDP growth over the medium term. As public funding cuts threaten key sources of research and development (R&D), the authors argue that the nation’s innovative edge relies heavily on strong government support for fundamental research.

The US has consistently been recognized as a global innovation leader. From the development of semiconductors and the internet to breakthroughs in biotechnology and artificial intelligence, America’s scientific achievements have thrived in an ecosystem that harmonizes public funding with entrepreneurial initiative. However, recent discussions regarding potential budget cuts to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the National Science Foundation (NSF) arise at a time when countries such as China and members of the EU are intensifying their public investments in advanced technologies. This trend has sparked renewed concern regarding the extent to which the US’s innovation prowess depends on government funding.

A recent study (Gazzani et al. 2025) offers new empirical insights into the macroeconomic ramifications of the post-war American innovation framework, which was first articulated by Vannevar Bush in *Science, the Endless Frontier* (1945). By analyzing newly digitized US patent data that distinguish between funding sources and ownership structures, we find that government-funded but privately owned patents, which represent only 2% of all patents, contribute around 20% to fluctuations in US productivity and GDP growth over the medium term. These public-private innovations also stimulate additional private R&D, reinforcing the significant returns from government support for basic research.

Our analysis implies that much of the US’s technological dynamism is not solely a product of market forces but rather emerges from what can be described as the visible hand of government-enabled innovation.

The Global Race for Innovation Leadership

The role of the US government in shaping technological advancement is often underestimated. Yet, in the current climate of fiscal concern, public research funding is facing unprecedented scrutiny. The NIH and NSF — integral components of American scientific advancement since the 1950s — are experiencing renewed challenges just as China invests substantial resources in fields such as artificial intelligence, quantum computing, and renewable energy technologies. The EU is also expanding its Horizon Europe initiative and national innovation funds in response to its stagnating productivity growth (see Aghion 2024, Bloom et al. 2019).

This tension is not new. Mazzucato (2013) has long argued that government agencies have effectively acted as the “entrepreneurial state,” mitigating risks associated with fundamental research that private firms later commercialize. Recent academic work has explored this relationship from various perspectives — including the macroeconomic impacts of public R&D (Fieldhouse and Mertens 2023) and the link between fiscal policy in a high-debt context and productivity growth (Fornaro and Wolf 2025). Our findings contribute to this body of research by detailing how diverse forms of public and private innovation have influenced US productivity dynamics over the past seventy years.

Mapping America’s Innovation Architecture

Following Bush’s vision, the post-war US innovation landscape has relied on three fundamental pillars:

- Government funding for public-interest initiatives

- Universities and research institutes dedicated to fundamental research

- Private companies that commercialize the resulting knowledge.

Utilizing the Government Patent Register database (Gross and Sampat 2025), we categorize all US patents granted since 1950 into three distinct groups:

- Public–private (funded by the government but owned by private entities)

- Private–private (fully privately funded and owned)

- Public–public (both funded and owned by the government)

Subsequently, we correlate these time series with macroeconomic indicators such as total factor productivity (TFP), GDP, R&D expenditure, and investment. By controlling for business cycle effects and ensuring that our innovation measures are unaffected by fiscal and monetary shocks, we isolate the medium-term relationships between innovation activities and overall economic outcomes.

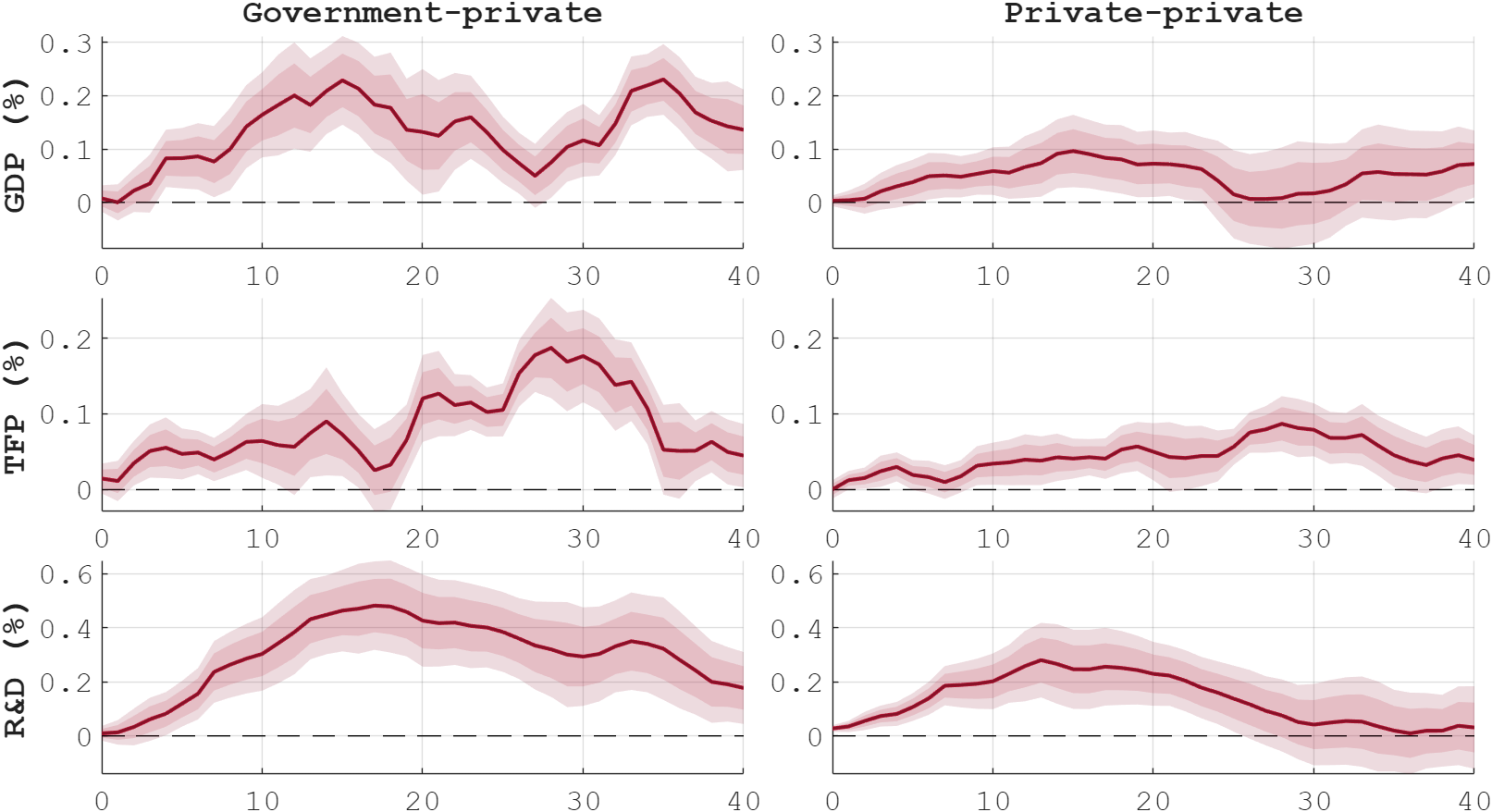

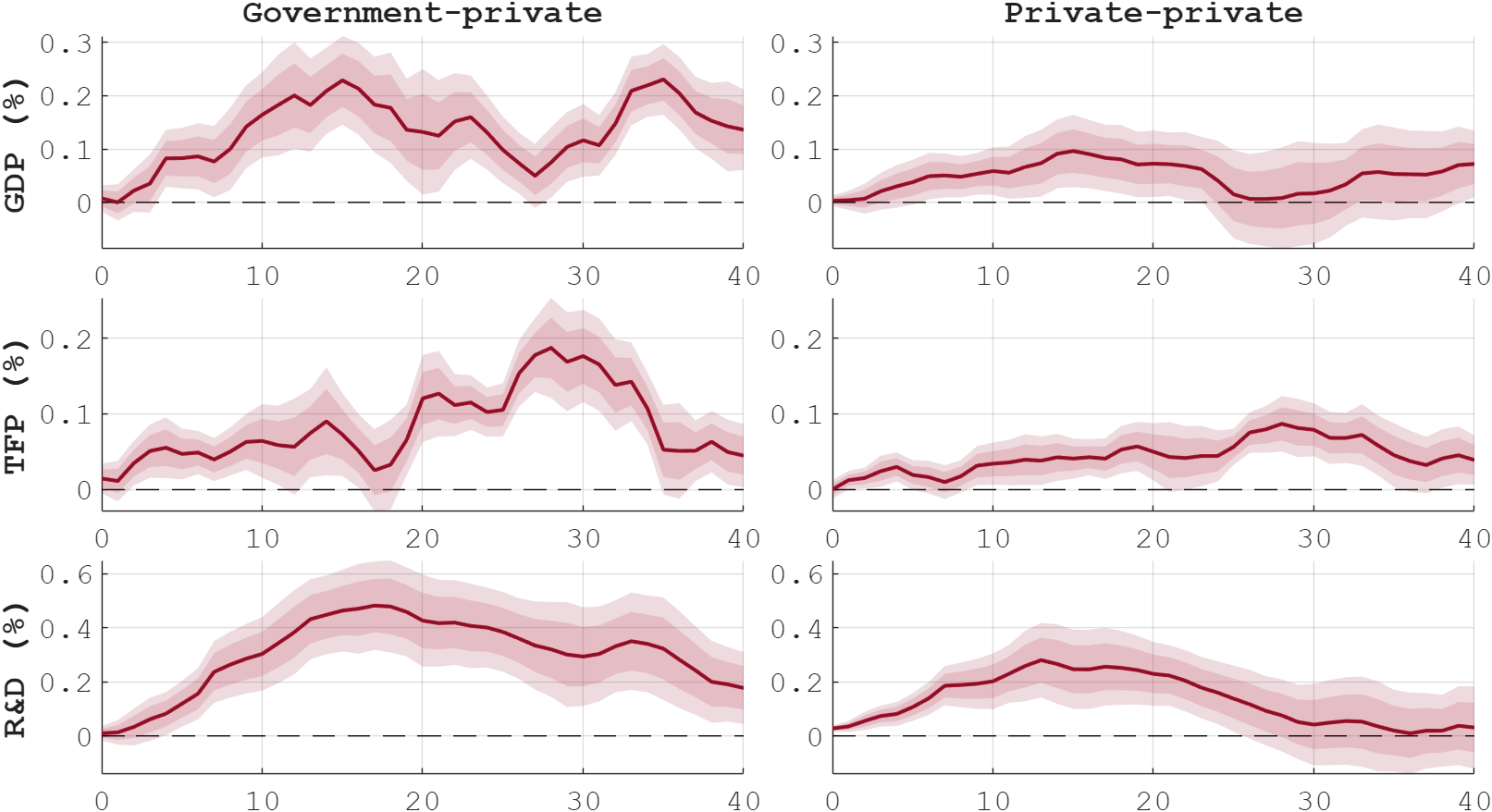

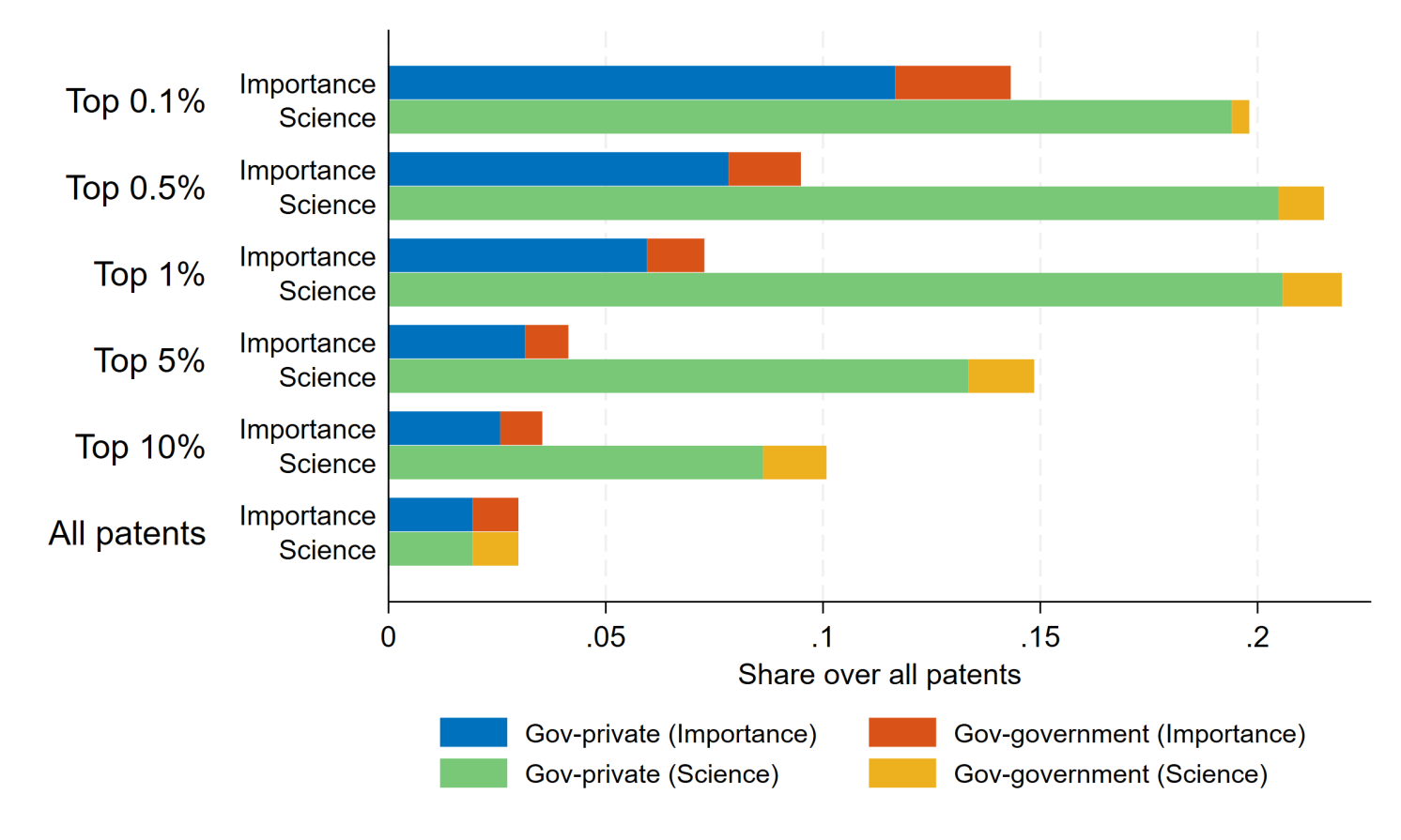

The results are illuminating. Figure 1 illustrates that public-private patents (first column) have the most substantial medium-term impacts on output (first row) and productivity (second row), doubling the effects of private sector innovations over similar time periods (second column). Government-funded but privately held patents also correlate with increased private R&D spending, business investments, and real wages. Even though public–private patents represent a mere 2% of the total, they account for approximately one-fifth of fluctuations in medium-term GDP and TFP (Figure 2). Although public–public patents are not depicted here, their average effects are muted, albeit they feature some of the most groundbreaking advancements in health and biotechnology. This trend holds true across ten econometric methods, consistently underscoring the pivotal role of government-funded research in driving medium-term productivity growth.

Figure 1 Macroeconomic effects of innovation

Notes: The figure displays the dynamic effects of innovation shocks in each category of patents (public-private, private-private, public-public; by column) on (log) real per-capita private GDP and (log) TFP. The estimates are done by means of local projections, normalizing the shock to increase total patents by 1% on impact. Shaded areas report 68% and 90% confidence intervals. Sample: 1950:Q1-2015:Q4.

Figure 2 Contribution of innovation to GDP and TFP

Note: The figure shows the forecast error variance contribution of innovation shocks in two patent categories (public-private and private-private) on (log) real per-capita GDP expenditure and (log) TFP (by row). Shaded areas report 68% and 90% confidence intervals.

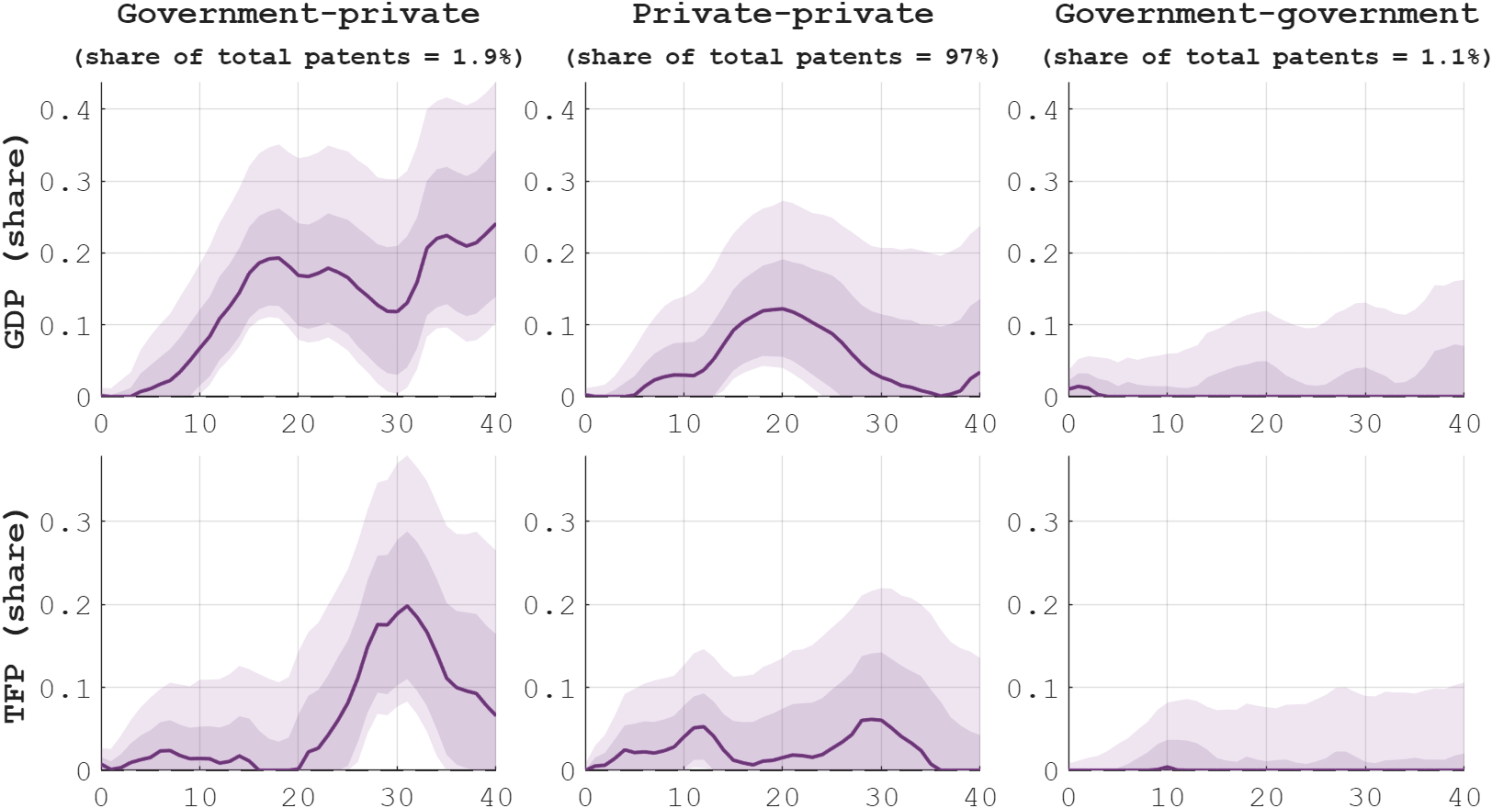

Why do government-funded patents hold such significance? Because they are often more basic compared to those developed with private funding. Basic research enhances the knowledge frontier, yielding broadly applicable insights that trigger extensive spillovers, thereby amplifying innovation throughout the economy. Figure 3 indicates that government-funded patents represent a substantial proportion of the most basic patents, based on metrics that assess their similarity to subsequent patents (‘importance’) and the number of citations from scientific papers (‘reliance on science’). Although these patents are fewer in number, they tend to be significantly more fundamental than their privately funded counterparts.

Figure 3 Basicness of publicly funded patents

The Multiplier of Public–Private Innovation

The macroeconomic trends we identify align with Vannevar Bush’s post-war vision: the government should sponsor basic research that private investors shy away from due to high risks or upfront costs, while universities and businesses bring these discoveries to fruition. This synergy between public funding and private ownership generates substantial spillover effects.

A preliminary calculation indicates that each dollar invested in public R&D yields between eight and fourteen dollars in overall GDP, more than double the return received from innovations strictly financed by private investors. These multipliers reflect recent findings showing that public R&D stimulates, rather than stifles, private innovation (see Bloom et al. 2019, Myers and Lanahan 2022, Bergeaud et al. 2025).

NIH, NSF, and the Geography of Transformative Science

When examining individual federal agencies, the NIH and NSF emerge as the most effective sources of innovation support. Patents developed with their backing demonstrate the strongest connections to medium-term productivity gains, output increases, and business sector R&D activities. In contrast, patents funded by the Department of Defense or NASA show weaker macroeconomic associations.

The sectoral distribution of innovations further clarifies this discrepancy. In health and biotechnology — sectors predominantly funded by the NIH — publicly financed patents significantly outperform their private counterparts. This trend reflects the ‘public good’ nature of biomedical research and the lengthy timelines linked to medical discoveries that private entities may struggle to justify to stakeholders. Similar patterns manifest in basic energy research, where projects funded by the Department of Energy have also generated notable spillovers into private R&D, consistent with findings from Myers and Lanahan (2022).

Who Delivers the Biggest Impact?

Beyond federal agencies, the data reveal significant variations across different types of innovators. Research institutes and universities tend to produce the most impactful patents when they receive government support. However, when universities rely solely on private funding, their macroeconomic contributions are roughly halved.

Among private entities, it is notable that start-ups and venture capital-backed firms emerge as more effective innovators than established corporations, but this advantage only materializes with government assistance. Without public funding, their productivity benefits dissipate. These insights suggest that public financing does not replace entrepreneurial efforts; it enhances them.

The synergies between the public and private sectors resonate with arguments from Aghion et al. (2023) and Mitra et al. (2024) regarding the structuring of innovation policy in Europe: when the state absorbs early-stage risks, the private sector is positioned to scale up transformative technologies. The post-war American experience provides a quintessential illustration of this dynamic.

The Macroeconomics of Innovation Policy

The overall correlations we observe are substantial enough to clarify key fluctuations in US productivity growth since the 1950s. Periods of heightened public-private innovation align with the prosperous 1950s, the flourishing 1990s, and the productivity stagnation seen in the 2000s. If the pace of government-funded innovation during the 2000s had matched that of the 1990s, total factor productivity in 2007 would have been 5–10% higher than it actually was.

This underscores a frequently overlooked aspect of innovation policy: its macroeconomic externalities. When budget cuts reduce public research spending, the repercussions extend well beyond the laboratory, dampening private R&D, slowing productivity growth, and ultimately diminishing potential output. Conversely, targeted investments in science can act as a stabilizing force in the medium term — a conclusion in line with the fiscal-growth literature regarding ‘productive government spending’ (Antolin-Diaz and Surico 2025, Fornaro and Wolf 2025).

Policy Lessons

Our findings highlight three critical lessons for policymakers:

- Safeguard public research budgets. Reducing funding for NIH and NSF may offer short-term savings but poses significant risks to the long-term drivers of US productivity and international competitiveness.

- Capitalize on public-private synergies. The most groundbreaking innovations arise when the government finances fundamental research that private entities then develop into practical applications. Policies should continue to promote this collaborative model.

- Prioritize investment in basic science. Research institutes and universities provide the highest macroeconomic returns for each dollar of public support, particularly in health, energy, and emerging technology sectors.

As the US grapples with increasing competition from state-driven innovation models globally, evidence spanning seven decades is unequivocal: the nation’s technological leadership is a public accomplishment. As Vannevar Bush cautioned in 1945, “While industry will meet the challenge of applying new knowledge, basic research is inherently non-commercial. It requires dedicated attention that industry alone cannot provide.”

Authors’ note: The views expressed in this column do not necessarily represent the positions of the Bank of Italy or the European System of Central Banks.

See original post for references