The sharp increase in the diagnosis and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in American children has raised concerns among parents, educators, and health professionals alike. A recent article in the Wall Street Journal probes this troubling trend, particularly the alarming fact that even kindergarten-aged children are being prescribed ADHD medications. These medications often prove ineffective or lead to undesirable side effects, resulting in a cycle of adding more drugs to an already precarious situation. This is especially concerning given the ambiguous criteria for ADHD diagnosis and the lack of comprehensive data on the long-term effects of these drugs on developing brains.

The article highlights that demographic factors like sex, race, and foster-care status do not account for the growing gap in ADHD diagnoses.

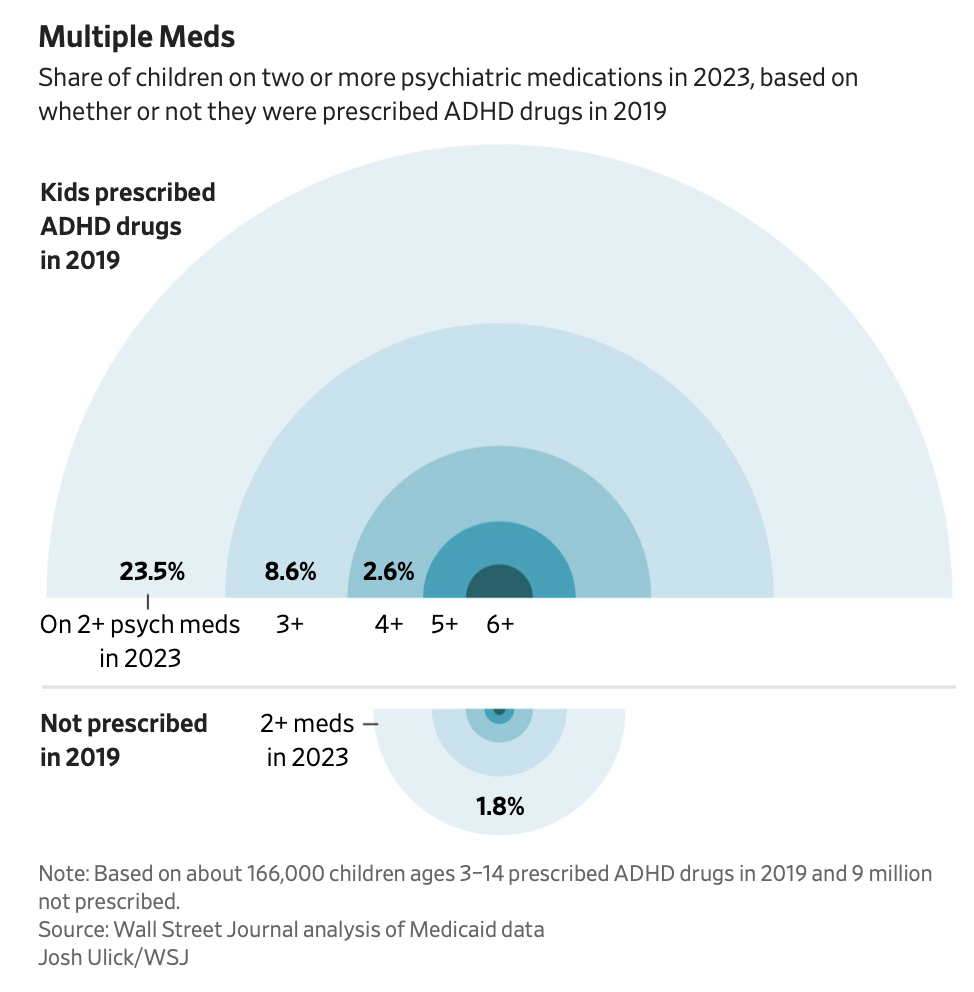

The statistics are startling: approximately 7.1 million children aged 3 to 17 are receiving treatment for ADHD, which accounts for more than 10% of this age group. Data from Medicaid, covering a sample of 166,000, reveals that among those prescribed ADHD medications in 2019, only 37% had received any form of therapy.

While there are certainly instances where a child’s behavior may necessitate intervention, it’s crucial to recognize that medication can be both beneficial in the short term and potentially harmful in the long term. Various societal changes, including increased environmental pollutants, early exposure to electronic stimuli, and rising anxiety due to economic pressures and family instability, may contribute to the observed rise in ADHD diagnoses.

For those who grew up in a more carefree environment, it is hard not to view the increased intolerance for typical childhood behavior as a significant factor. There was a time when children could be themselves without facing high expectations to conform to stringent behavioral norms.

It’s important to remember that the aim of public education has traditionally extended beyond academics; it has also included cultural acclimatization—learning to arrive on time, sit still, and follow adult authority. This structure prepares children for future workplace dynamics, but its effectiveness may be questionable.

Childhood dynamics have transformed over recent decades:

Less recess. In my own elementary school experience, there were typically three recesses each day. I find it hard to imagine how today’s children can remain still for extended periods. The CDC-funded Physical Activity Policy Research and Evaluation Network recommends only 20 minutes of daily recess, a stark reduction from what some schools once provided. The results of a 2025 survey on recess can be found here.

Although not catastrophic, the current situation leaves much to be desired.

Reduced walking to school. The lack of physical activity is widely thought to hamper focus. Research indicates that children in the U.S. exhibit a “low prevalence” of walking to and from school. If communities aren’t prepared to address this issue, short in-class exercise sessions could serve as an alternative.

Children in China are required to exercise between different lessons in school pic.twitter.com/yIIFXgJ6jR

— Historic Vids (@historyinmemes) January 17, 2024

Escalated performance expectations. The decline of free-range childhood coincides with increased academic demands on children at younger ages. This heightened pressure can be attributed to economic stratification and parental anxiety about college placements. In the past, performance metrics like grades and test scores didn’t become significant until middle school, but today, intense competition begins much earlier.

Schools as childcare centers. The concept of the “latchkey” child is now more common, as working parents increasingly rely on schools for full-day care.

A poignant story highlights the struggles of a now 29-year-old, Danielle Gansky, who was pressured into treatment at her upscale private school after being flagged for her lack of focus:

Danielle Gansky was 7 years old when an administrator at her upscale private girls’ school in suburban Philadelphia flagged problems with her academic performance. She was a bubbly and creative kid, but she was easily distracted in class and her schoolwork was sloppy.

The school told Gansky’s mother that the girl should see a psychiatrist, who diagnosed her with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, or ADHD, and prescribed a stimulant. Concerned that Danielle might get kicked out if her focus didn’t improve, her mother broke into tears and agreed.

This situation reveals the heavy-handed nature of the school and the anxiety of her parent. What significance does it hold if an otherwise bright 7-year-old struggles with conscientiousness at that age? In contrast to the past, parents today might be more inclined to challenge educators regarding academic assessments but remain silent when their child receives what could the considered an unjust behavioral grade.

Or perhaps there are parents who trust in “better living through chemistry.” Many high school students now have easy access to Adderall as a performance enhancer, despite studies that debunk its effectiveness on academic performance.

The Journal notes that many parents are driven by fear of their children falling behind or being expelled:

The decision to treat ADHD with medication is often made by desperate parents trying to keep their kids from falling behind or being kicked out of school or daycare, parents and mental health clinicians say. For preschool-age kids, the drugs are often dispensed against pediatric guidelines, which call first for behavioral therapy, a treatment that can be hard to get. And mental health providers say the drugs are frequently prescribed to treat childhood trauma that has been misdiagnosed as ADHD.

Despite calls for caution from experts:

“We need long-term studies following young people to fully understand the effects of psychiatric medications on the developing brain,” said Dr. Mark Olfson, professor of psychiatry and epidemiology at Columbia University Irving Medical Center. Antipsychotic medications are of particular concern, he said. Some studies suggest that adults taking antipsychotics for long periods experience cognitive decline, but long-term studies haven’t been conducted on children, he said.

“The best scientific evidence suggests that it is very rare for two or more medications in kids to be helpful and there are concerns about safety, because there can be additive adverse effects of different types of medications,” said Dr. Javeed Sukhera, a child and adolescent psychiatrist and chair of psychiatry at the Institute of Living at Hartford Hospital in Connecticut.

The Journal’s analysis indicates that approximately 5,000 providers ordered ADHD medications for at least 100 children each from 2019 to 2022, with one in four patients receiving additional psychiatric drugs. A small subset of these providers prescribed combinations at significantly higher rates, raising alarms about the potential risks involved.

Many parents, feeling pressured by schools, turn to pediatricians or psychiatric nurse practitioners who may lack the specialized training required for pediatric mental health, further complicating matters. Alexandra Perez, a clinical psychologist at Emory University, notes that some of the children she treats are as young as 4 and often prescribed multiple psychiatric medications due to behavioral issues mistakenly identified as ADHD. She advocates for Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) to tackle these challenges effectively.

Additionally, the Journal recounts troubling cases, including that of a disruptive 3-year-old prescribed multiple medications, underscoring the risks of experimental drug regimens.

The Journal found that patients starting ADHD medications at a young age tend to be prescribed additional psychiatric drugs. By 2023, over 23% of this group—more than 39,000 children—were on multiple psychiatric medications simultaneously.

The trend raises concerns about the long-term health implications for children. A past study examining children diagnosed with ADHD found that many were also given additional mental health diagnoses, often after being put on multidrug programs without robust evaluation.

As someone with a brother who exhibited behaviors resembling ADHD, I often think about how different his experience would be if he were a child today. He eventually thrived despite initial struggles and became a published author. It makes one ponder the potential consequences of modern approaches to childhood behavior.

_____

1 I had my own mischief, believing some assigned tasks were frivolous. This led to me finishing quickly and then chatting with teachers, which was not a behavior expected at the time.