Hello, readers! Today, we’re diving into an intriguing exploration of group dynamics through the lens of the immensely popular online game, Wordle. While I may not personally engage in gaming, it’s clear that many of you are familiar with this word puzzle. Rajiv Sethi provides valuable insights into how collective performance in Wordle can shed light on other skill-based activities, revealing some surprising findings along the way.

Sethi cites the renowned quant trader Cliff Asness, who has expressed concerns about the declining accuracy of crowd judgments—the assessments reflected in market prices—over the years without offering a clear explanation. I have a theory of my own: the business community has become significantly more adept at propaganda and spin. I recall how a Wall Street Journal reporter who opened the Shanghai office in 1993 returned in 1999, astonished by the evolution of business journalism. The rapid rise of the internet had nearly eradicated typical publishing deadlines, leading to shortened news cycles that often prevented reporters from thoroughly investigating stories before publication. Furthermore, companies have become more skilled at manipulating public perception, creating an environment where fewer people possess well-informed viewpoints.

By Rajiv Sethi, Professor of Economics, Barnard College, Columbia University; External Professor, Santa Fe Institute. Originally published at Imperfect Information

This post aims to delve into the topics of strategic diversity, meritocratic selection, and the presence of asset price bubbles. But first, let’s take a closer look at Wordle, which has captured the attention of more than a million daily players.

The New York Times acquired Wordle in 2022 and introduced several features that yield fascinating data. Players can now measure their performance against an algorithm known as the wordlebot, designed to complete the puzzle with minimal steps. The bot generally solves the puzzle within three or four attempts, evaluating each player’s submissions based on their skill and luck. Scores range from zero to 99. While some players may surpass the bot daily due to luck, no one has consistently outperformed it based solely on skill.

However, I propose that a large, randomly selected group of independent players can, in fact, consistently outperform the bot. Initially, I attributed this phenomenon to widespread cheating, but it turns out that the scale of cheating is too minor to explain the results—something far more intriguing is at play.

For instance, let’s examine the sequence of entries by the bot on November 26:

Notice that the second word here is eliminated based on feedback from the first. This is a common strategy for the bot—limiting choices to feasible words at every stage is not the most efficient method for minimizing the number of steps needed.

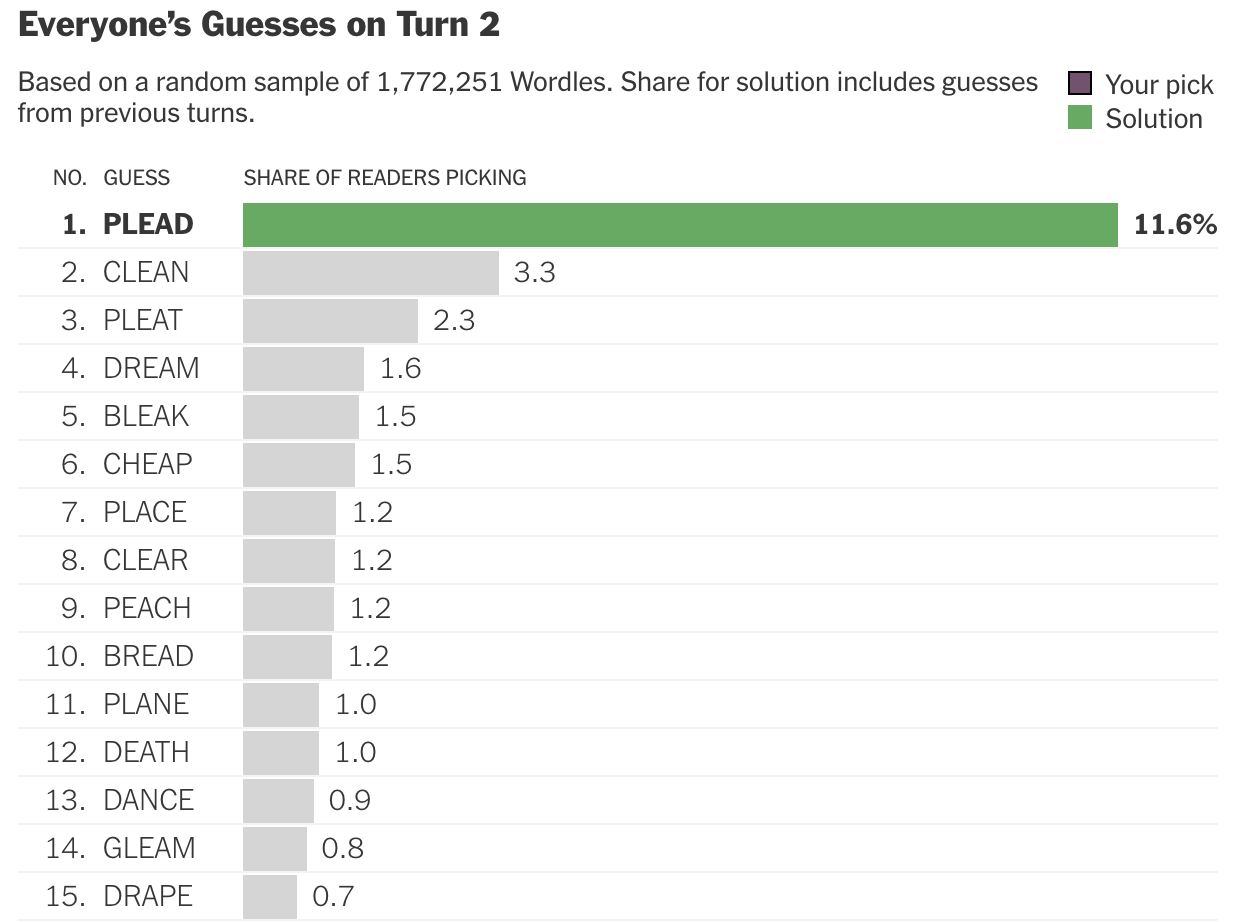

In contrast, most human players tend to select words that haven’t yet been ruled out, leading to compelling outcomes. Here are the most frequently chosen entries at the second stage for the November 26 puzzle, based on approximately 1.8 million responses:

It’s noteworthy that the word chosen most frequently happens to be the solution itself. If a large, randomly selected subset of players submitted their choices to an aggregator that selected the most popular word, the crowd would have outperformed the bot that day.

This trend is not isolated to a single day. Based on data collected since November 1, the crowd never took more steps than the bot and required strictly fewer steps on 85 percent of occasions. On average, the bot completed the puzzle in 3.5 steps while the crowd did so in just 2.4 steps. Notably, the crowd found the solution in merely two steps more than a quarter of the time, while the bot took four.

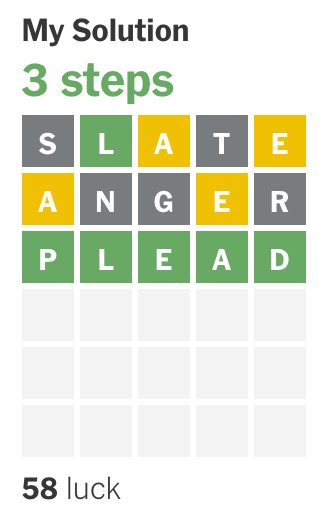

Initially, I suspected that cheating might explain this pattern, with players possibly using multiple attempts across different browsers or devices or seeking hints from others. While some instances of cheating exist—around 0.4 percent of players solve the puzzle on their first attempt, double the expected rate—this cannot account for the crowd’s average luck score, which was nearly the same as the bot’s: 54 for the bot compared to 56 for the crowd.

Here’s my hypothesis for the crowd’s success:

Firstly, there is considerable diversity in word choices during the first round. The top ten words chosen account for only about 30 percent of total selections on average, with hundreds of unique words used at the outset.

Secondly, in subsequent rounds, players tend to select only words that remain plausible based on their previous selections. Each player operates with a set of words still in play, and the initial diversity of selections means these sets differ significantly in both size and makeup. Given that every set must include the actual solution, the solution inevitably emerges as the most frequently selected word. Even in cases where players randomly select from remaining feasible options, the most likely choice at the second stage is still likely to be the correct solution.

By the third stage, the most popular choice is almost guaranteed to be the right answer, a result corroborated by the available data. Since November 1, the crowd has successfully solved the puzzle in two steps roughly 60 percent of the time and has never needed more than three steps.

This brings about an intriguing hypothesis: a large pool of randomly selected participants may find the solution faster than a similarly sized group of highly skilled players. The latter group would lack significant strategic diversity, echoing the bot’s behavior. This hypothesis is worth testing, and if validated, would offer strong evidence supporting Scott Page’s assertion that under certain conditions, cognitive diversity can outweigh skill level. This has profound implications for how we define merit—as a characteristic of teams rather than individuals.

The crowd’s triumph in Wordle mirrors the dynamic witnessed during audience polls in the quiz show Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? Contestants can opt to survey the audience, where each member independently shares their best guess for the question posed. The most popular answer enjoys a remarkably high success rate, often reaching 95 percent for questions of low to moderate difficulty.

In a recent discussion with Joe Weisenthal and Tracy Alloway, Cliff Asness outlined why audience polling is so reliable:

From my observations, it seems effective virtually every time, even with difficult questions. Imagine a hundred individuals in a room, with ten knowing the answer. The rest may distribute their guesses across the four possible answers. If the ten choose B, you would look to select B based on its higher frequency. This strategy tends to work.

But a crucial assumption is at play. The audience must operate independently of one another. If they were allowed to discuss, the knowledgeable individuals could influence the guesses of others. This opens the door to distortions and reduces the accuracy of the collective guess. The Wordle audience thrives precisely because it consists of millions of players worldwide, most of whom engage independently.

While Cliff Asness studied under Eugene Fama at the University of Chicago, his views have evolved significantly. He believes that markets have become less efficient over recent decades. He noted a shift from adherence to Fama’s theories toward a greater reliance on behavioral insights. Asness, along with many others, expresses concern that we might currently be navigating an AI bubble.

The sustainability of asset market bubbles hinges on the challenges of timing a potential crash. Even when many perceive an asset as overvalued, those betting against it might exit too early, incurring losses before the downturn begins. This was seen by many investors during the tech bubble of 1999 and early 2000. Such challenges indicate a problem of coordination—speculating on price declines proves exceptionally risky when done in isolation. While coordinated action eventually occurs, those acting prematurely may suffer significant losses.

We may or may not find ourselves within an asset price bubble, but dismissing cautions from Cassandra-like figures based solely on logic would be incredibly shortsighted. Crowds display remarkable wisdom in low-stakes scenarios—such as quiz shows and casual games—yet succumb to extraordinary folly when the stakes soar. While this might appear paradoxical initially, it becomes clear when we consider the associated incentives with the right seriousness and care.