Greetings! Servaas Storm offers a compelling and sobering perspective on the current hype surrounding AI and the stock market, emphasizing the numerous reasons why U.S. players may struggle to fulfill their grand promises.

One minor criticism, more related to presentation, is that Storm initially presents AI borrowing as though it’s primarily undertaken by large companies. While that’s partly true, he later acknowledges the growing use of off-balance-sheet vehicles, which investors have surprisingly embraced.

I haven’t delved deeply into these financial structures, but I question how truly off-balance-sheet they will remain in practice. During the financial crisis, banks involved in securitizing credit card receivables found themselves absorbing losses, despite claims the entities were structured for arm’s-length transactions. Lenders essentially challenged them to sell more—highlighting the difficulty banks faced in offloading these receivables in light of prohibitive capital retention costs.

In at least one data center deal, Meta secured four successive five-year leases. In my youth, we would categorize such commitments as operating leases, essentially treating them as debt. This practice seems outdated. If the primary business falters, will Meta default on its lease payments?

By Servaas Storm, Senior Lecturer of Economics, Delft University of Technology. Originally published at the Institute for New Economic Thinking website

Introduction

Three years have passed since the public launch of ChatGPT on November 30, 2022. This groundbreaking Large Language Model (LLM) astonished users, demonstrating capabilities previously thought impossible. Within just five days, over one million individuals had signed up to interact with the AI—a growth rate 30 times faster than Instagram’s and six times that of TikTok during their launches. By October 2025, ChatGPT was being utilized by over 800 million users weekly, making it the fastest-growing consumer product in history. OpenAI, which began as a non-profit in 2015, rapidly became a household name, now valued between $500 billion and $1 trillion in anticipation of an initial public offering. Riding the wave of LLM technology, Nvidia, responsible for roughly 94% of the GPUs used in the AI sector, reached a market capitalization of $5 trillion by October 29, 2025—dramatically increasing from $0.4 trillion in 2022. Currently, Nvidia holds approximately 8.5% of the S&P 500 Index, while the so-called ‘Magnificent 7’ (Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, Nvidia, and Tesla) collectively represent around 37% of the index.

The substantial investments in data centers by a handful of hyper-scalers are fueling growth in an otherwise stagnant U.S. economy. The nation appears to be doubling down on its pursuit of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) by building increasingly vast computing infrastructures that require more GPUs, energy, cooling resources, and data than ever before.

However, as we approach the three-year anniversary of ChatGPT’s launch, concerns are emerging that the aggressive scaling of LLMs to achieve AGI may be misguided. Whispered speculations about a possible bubble in the AI boom are surfacing. The Trump administration, along with figures in the AI industry, appears increasingly anxious. At a recent Wall Street Journal tech conference, OpenAI’s Chief Financial Officer, Sarah Friar, indicated that government loan guarantees might be essential to fund the massive investments required to maintain the company’s competitive edge. Her message implied that OpenAI has become “too big to fail” (TBTF), a sentiment echoed by President Trump’s AI and crypto czar, David Sacks, who warned that any withdrawal from AI investments could risk plunging the economy into a recession. “We can’t afford to go backwards,” he asserted, reflecting support for Friar’s stance, although he later clarified his opposition to bailouts for individual AI companies.

Does History Repeat Itself, or Is This Time Different?

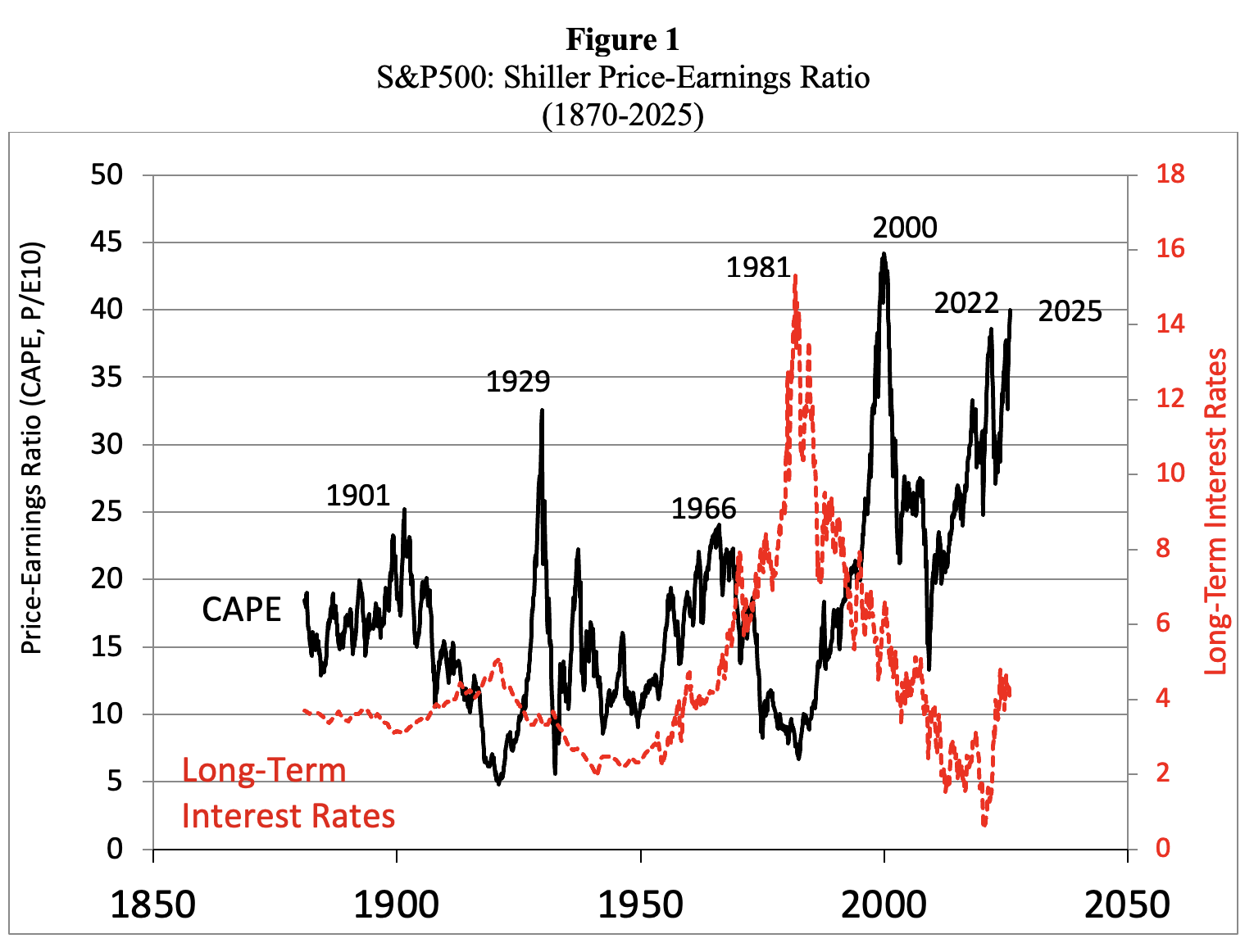

The U.S. stock market appears to be firmly entrenched in bubble territory. Figure 1 illustrates the S&P 500’s Shiller P/E Ratio, which reflects average inflation-adjusted earnings from the previous decade. Historically, a Shiller P/E above 30 often indicates speculative excess followed by market corrections. As of December 2023, this index climbed to 30.45 and has remained above 30; in November 2025, it exceeded 40.

Since 1871, the CAPE Ratio has surpassed 30 only five times. The first occurrence was in 1929, leading to an 89% drop in the Dow Jones Industrial Average value. The second instance happened nearly seven decades later during the late 1990s’ dot-com bubble when the Shiller P/E reached an all-time high of 44.19 in December 1999. Following the bubble’s burst, the S&P 500 lost 49% of its peak value.

The latest three instances of the Shiller P/E Ratio exceeding 30 occurred recently: from September 2017 to November 2018, from December 2019 to February 2020, and from August 2020 to May 2022. After each peak, the S&P 500 subsequently declined by between 20% and 33%. We find ourselves in the sixth incident of speculative excess today.

Source: Robert Shiller (2025), https://shillerdata.com/ (accessed on 15/11/2025)

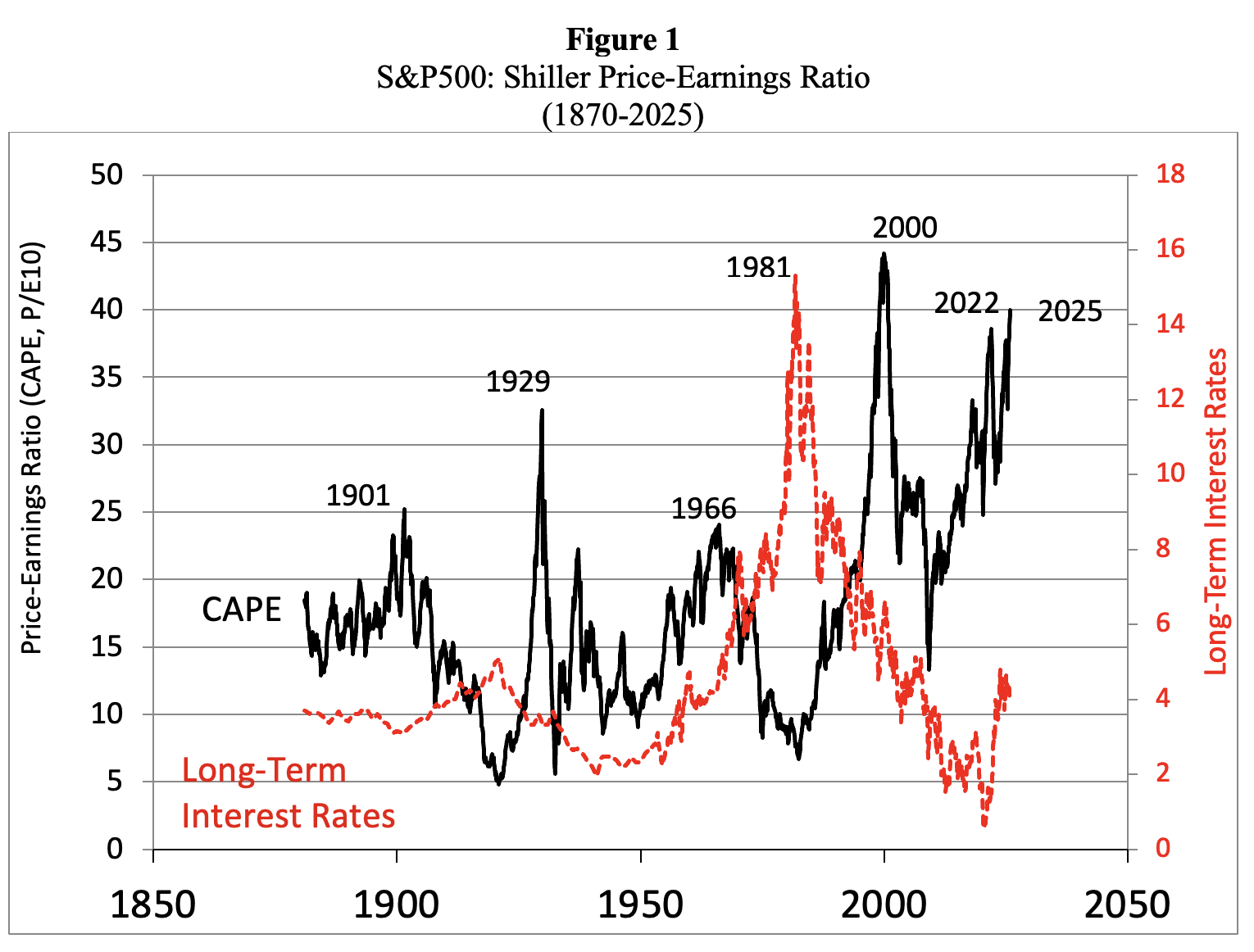

Nevertheless, the AI party continues unabated. Companies in the sector are in a race to expand data center capacities, convinced of an ever-increasing demand for AI services. Investments in data-center infrastructure by Amazon, Alphabet, Meta, and Microsoft are sharply rising, both in absolute terms and as a percentage of their sales (Figure 2).

JP Morgan Chase & Co anticipates that 122GW of data center capacity will need to be developed from 2026 to 2030 to accommodate the enormous demand for compute power (Wigglesworth 2025a). This additional capacity is estimated to cost between $5-7 trillion. For the year 2026, projected funding requirements for data centers are around $700 billion, potentially satisfied entirely by hyper-scalers’ cash flows and High-Grade bond markets. Notably, by 2030, funding needs are expected to exceed $1.4 trillion, surpassing current market capabilities and requiring alternative funding sources.

Source: Christopher Mims (2025), ‘When AI Hype Meets AI Reality: A Reckoning in 6 Charts.’ Wall Street Journal, November 14.

Significantly, many of the major financing deals are strikingly circular. Here’s a glimpse: Nvidia invests in OpenAI, which in turn purchases massive quantities of Nvidia chips. OpenAI sources its computing power from Oracle, which also procures Nvidia’s GPUs. Nvidia holds around 5% of CoreWeave, selling chips to them. Interestingly, CoreWeave’s primary client is Microsoft—an investor in OpenAI that shares revenue and collaborates with Nvidia, while AMD, a competitor to Nvidia, sought to win OpenAI as a client by offering warrants for them to acquire 10% of AMD at a nominal price. OpenAI is not only a client of CoreWeave but also a stakeholder. Nvidia has also invested in xAI and will supply processors to them. This intricate web of financial arrangements features revenue-sharing and cross-ownership at multiple levels.

However, transparency is lacking in these circular transactions. Questions arise about the source of the funding for these deals and the implications of these obscured transactions on the valuations of the public and private AI firms involved. Moreover, the competitive landscape concerning chip producers (Nvidia and AMD) and AI service startups (OpenAI, Anthropic, xAI, and Microsoft) remains murky. Thus, it’s no surprise that these outlandish circular deals—often totaling billions of dollars—are raising eyebrows and evoking memories of the circular financing that characterized the late 1990s, which artificially inflated dot-com stock prices without yielding genuine value.

Is It an AI Boom or Bubble?

Even Nouriel Roubini, a longtime pessimist in the economics community and a senior strategist at Hudson Bay Capital, has adopted a somewhat optimistic view, believing that the unprecedented surge in AI data-center investment can counterbalance the disturbances posed by Trump’s tariffs and geopolitical tensions.

However, the assertions from Huang, BlackRock, and Roubini may lack substance. The fundamental demand for Nvidia’s GPUs stems from the same cluster of companies that are gambling their futures on AI scaling. While AI data centers may not represent the “shovels of the AI gold rush,” they could merely become a black hole where billions vanish.

The surge in demand for GPUs and data-center resources could indeed be speculative if AI models fail to provide value for investors and do not meet the inflated expectations set by industry leaders. History is rife with instances where collective illusions led people to misjudge situations—such as the 2008 financial crisis, which resulted from a widespread mania.

The Irrationality of the AI Industry

The rush in the AI sector appears largely driven by a fear of missing out (FOMO), engendering a herd mentality in Silicon Valley and Wall Street alike. This fosters a wholehearted pursuit of ‘momentum,’ while fundamental values are often disregarded in favor of an exaggerated focus on the scarcity of critical resources (notably Nvidia’s GPUs). Additionally, confirmation bias runs rampant—individuals tend to seek out information that confirms their existing beliefs. For example, research has shown that relying on ChatGPT may inadvertently diminish idea diversity during brainstorming sessions, as noted in an article published in Nature.

It’s profoundly ironic that an industry striving to create ‘super-intelligence’—a concept imbued with complex and troubling connotations (see Emily M. Bender and Alex Hanna 2025)—exhibits such profound irrationality. Yet, anthropological studies on the local tech communities in Silicon Valley and Wall Street indicate that this irrationality may be ingrained in their culture. Members often engage in discussions about an impending AI apocalypse, hold almost religious beliefs in AI capabilities, exhibit unwavering trust in algorithms, indulge in techno-eschatology, and reveal a peculiar fascination for Hobbits and the lore of “The Lord of the Rings.” These individuals tend to speak of billions of dollars as mere ‘stuff’ necessary to fund compute resources essential for achieving AGI. “I don’t mind if we burn $50 billion annually; we’re constructing AGI,” remarked Sam Altman, confidently asserting, “We are making AGI, which will be expensive but utterly worthwhile.” In a tense exchange with podcaster and investor Brad Gerstner, Altman lost his composure when questioned about how everything is supposed to add up, brusquely responding, “If you want to sell your shares, I will find a buyer. Enough.”

More troubling signs of irrationality can be observed across the AI landscape. In the first half of 2025, numerous AI startups—despite lacking profits, sales, or even concrete pitches—secured billions in funding. For instance, the pre-revenue, pre-product AI company ‘Safe Superintelligence’, established by Ilya Sutskever, former chief scientist at OpenAI, raised $2 billion at a valuation of $32 billion in April 2025. Similarly, ‘Thinking Machines Lab’, founded by Mira Murati (previously the CTO at OpenAI), garnered $2 billion at a $12 billion valuation from investors including Nvidia, AMD, and Cisco in July 2025. Remarkably, this company has yet to release any product and has even declined to clarify its business objectives. “It was the most absurd pitch meeting,” recounted one investor who engaged with Murati, describing her presentation as, “We’re creating an AI firm with the best AI talent, but we can’t answer any questions.”

The brightest minds in AI are supposedly in leadership positions—so they assure us. A small number of labs, run by figures reminiscent of Tolkienesque fantasy, control the narrative surrounding frontier LLMs. The story they convey to the public asserts that they are on a noble mission to construct AGI for the benefit of all humanity, despite the complexity and potential dangers involved. Experts, such as Anthropic’s chief scientist Jared Kaplan, issue warnings about the risks presented by emerging autonomous super-intelligence, echoing sentiments previously expressed by Geoffrey Hinton, who predicts impending societal collapse once AI surpasses human intelligence. The overstated assertions escalate, claiming that future superintelligence could eliminate human jobs since it would be more effective and cost-efficient than human labor. This raises red flags: attaining AGI is viewed as gravely serious and potentially hazardous, yet developers assert their capability to manage these risks. They contend that AGI will necessitate extensive resources—such as data centers, land, electricity, and water—but assure us that the outcomes will be transformative and universally beneficial.

Conversely, what these developers communicate to their investors is quite different; they are building technology that could “essentially perform tasks that you will pay for,” including automating jobs, potentially rendering workers redundant or relegated to gig employment under corporate oversight. Emily M. Bender and Alex Hanna (2025) observe, for instance, how the National Eating Disorders Association in the U.S. replaced its human hotline operators with a chatbot shortly after the staff voted to unionize. Similarly, AI algorithms are being utilized by landlords to maximize rents, while the healthcare sector employs AI technologies to systematically deny patients essential coverage. Moreover, the military benefits from AI applications, as evidenced by defense contractor Anduril, which develops autonomous drones and other AI-enhanced technologies.

This environment has led the AI industry to persuade financial institutions, affluent platform companies, and wealthy venture capitalists to invest in the training of LLMs and the sprawling infrastructure of giga-data centers, fueling the current AGI frenzy in the U.S. In a new working paper, I contend that this AI data-center investment surge is a bubble poised to burst, likely sooner rather than later. The ensuing fallout will be detrimental to the broader U.S. economy—not only due to the inevitable downturn but, more fundamentally, because of the squandered resources tied up in the lofty dreams of a few privileged tech billionaires, who have begun seeking taxpayer subsidies and government loan guarantees (Cooper 2025). The impending AI bubble is set to burst for four key reasons.

The Revenue Fallacy

There is no viable scenario in which the immense spending on data center infrastructure (estimated to exceed $5 trillion over the next five years) will prove fruitful; AI revenue projections are wildly optimistic for several reasons:

- The costs associated with training AI models and running inferences are escalating. Alarmingly, compute demand is growing faster than the efficiency of the tools generating it. Consequently, the operational costs of inference are rising more rapidly than the AI companies’ revenues. This observation comes from thorough financial analysis of OpenAI’s quarterly reporting by Ed Zitron. The growth rate for AI’s compute demand—driven by a belief that larger AI computing power yields better output—surpasses Moore’s law. As a result, the demand for GPUs among AI companies is soaring, and Nvidia, which enjoys a near-monopoly with a 94% market share, can set high prices for its latest chips or hefty fees for leasing GPUs to AI companies.

- Despite a 98% reduction in the cost per million tokens for LLM inference—from $20 in late 2022 to around $0.40 in August 2025 (Barla 2025)—AI’s inference costs are rising rather than declining. This increase is problematic since the industry is utilizing significantly larger training datasets compared to just one or two years ago and requires more tokens for test-time computing. This method allows for extended context windows and more extensive model suggestions, leading to considerable boosts in processing token consumption. For instance, while a typical enterprise query used fewer than 220 tokens in 2021, models such as GPT-4 Pro and ChatGPT-5 handle roughly 22,000 tokens in a single interaction. By 2030, token utilization per query could soar to between 150,000 and 1,500,000, depending on task complexity. Thus, despite the decreasing cost per token, AI application inference costs have surged around tenfold over the last two years (as detailed in the working paper); scaling operations are extraordinarily expensive.

- Unfortunately, customers may not be willing to pay adequately for the relatively modest services offered by LLMs, especially considering a likely oversupply of LLM services. Currently, only 5% of OpenAI users (approximately 4 million) are paying subscribers, contributing a minimum of $20 monthly. The remaining 95% of everyday users enjoy free access and remain unconvinced of the value of AI-powered devices and services. The 1.5 million enterprise customers utilizing ChatGPT contribute more to revenue, yet businesses have access to cheaper Chinese LLMs, such as DeepSeek and Alibaba Cloud, which deliver comparable performance while offering consistent price reductions. For example, for processing 500 million tokens monthly, a news site would incur $70 for DeepSeek R1 versus $3,750 for ChatGPT o1. This significant price difference is hard to rationalize concerning any superior performance from the OpenAI tool. Price competition inevitably drives down costs for U.S. AI firms, further undermining their business models. OpenAI recently declared a “Code Red” after losing 6% of its user base within a week due to the threat posed by Google’s new Gemini-3 model. OpenAI’s substantial lead appears to be dwindling swiftly: should investors choose to withdraw, it will become increasingly challenging to sustain operations, with a potential dramatic decline in OpenAI’s valuation—similar to what happened with WeWork, whose value plummeted from $47 billion to the brink of bankruptcy. If OpenAI falters, Nvidia’s stock value will likely follow suit.

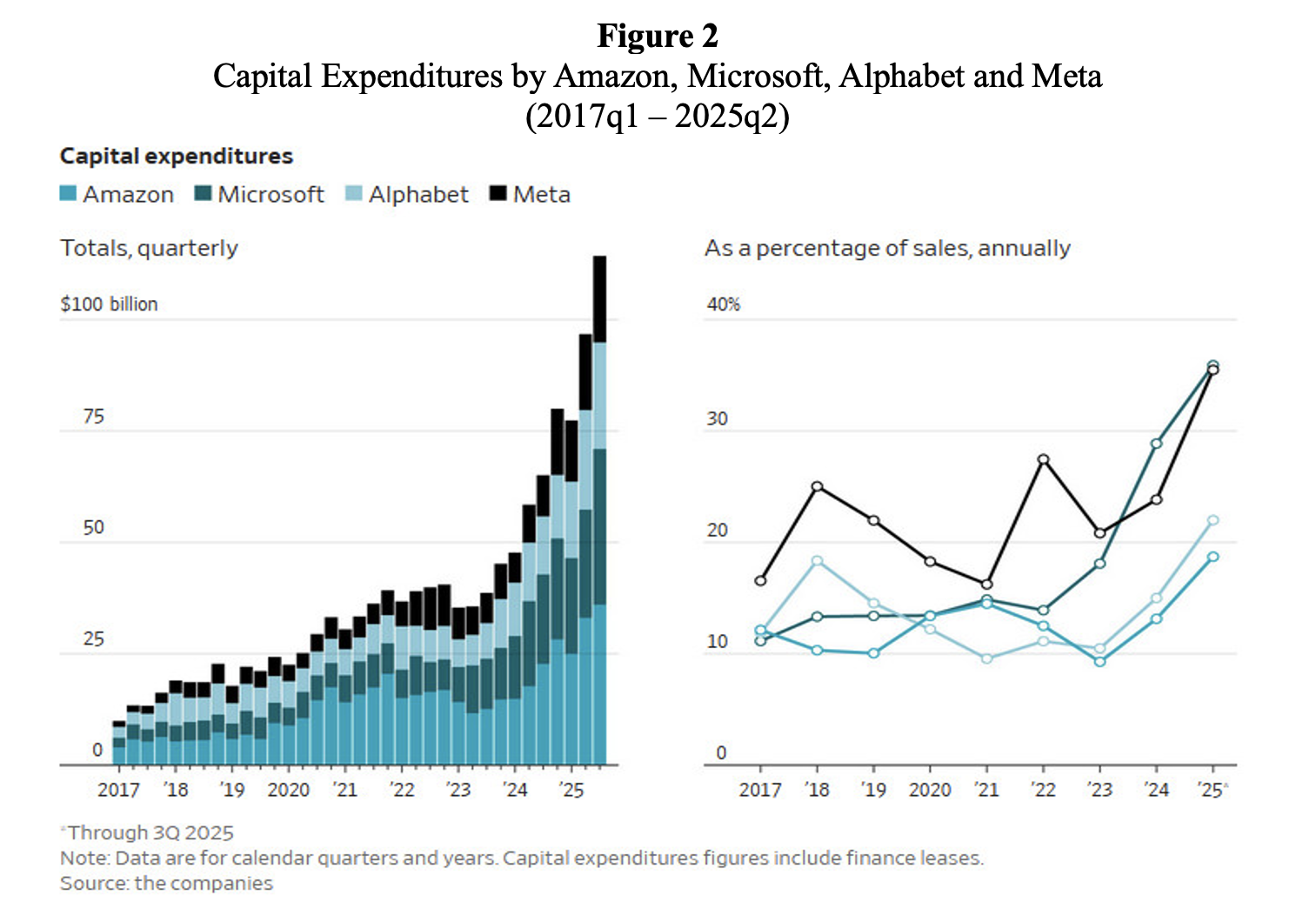

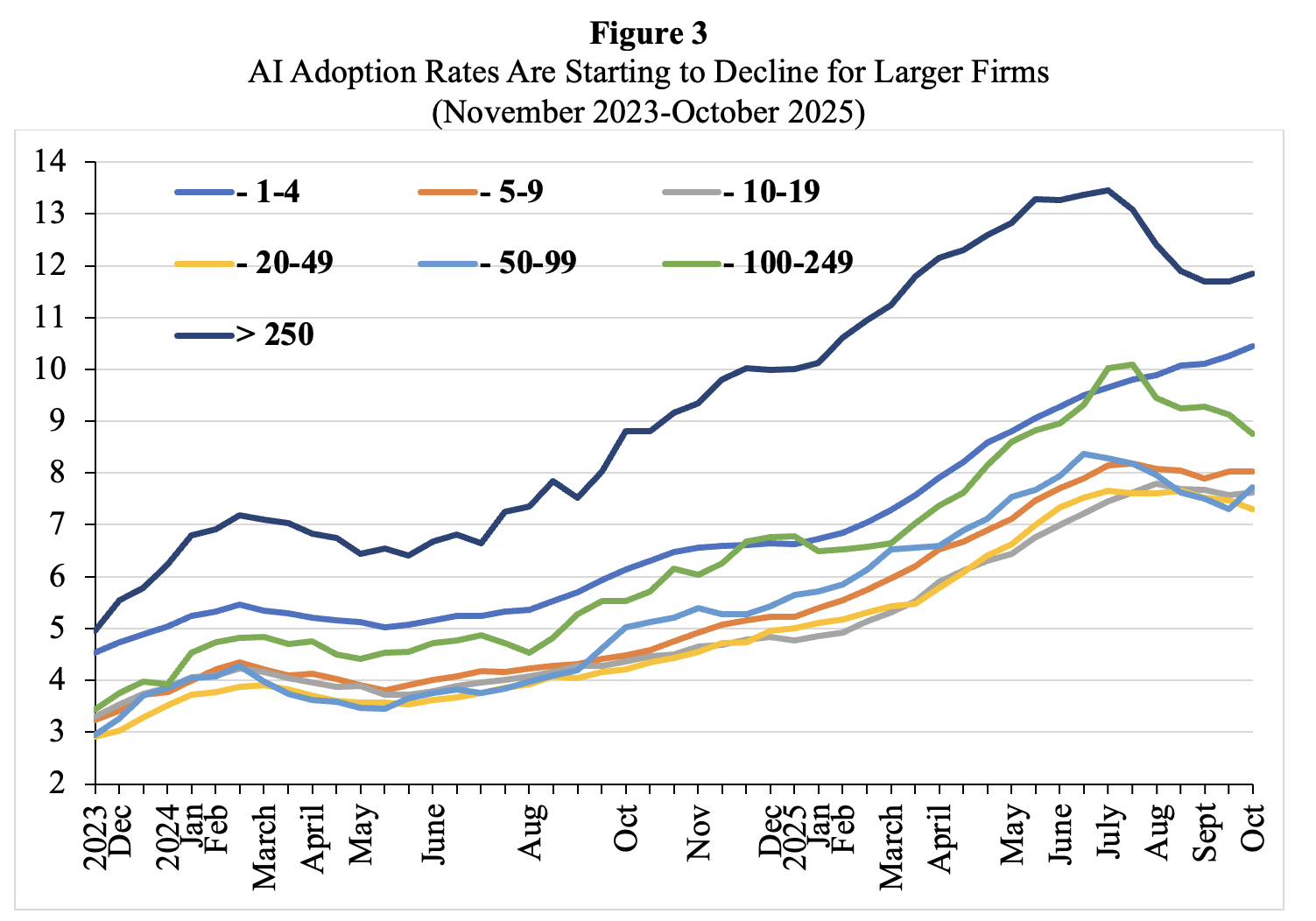

- Lastly, user satisfaction with AI tools appears to be stagnating or, in some instances, declining. Enterprises are showing diminished enthusiasm for their AI systems. The MIT study revealed that only 5% of businesses are experiencing returns on their generative AI investments. Similarly, McKinsey’s findings in 2025 suggested that two-thirds of companies were merely piloting their AI initiatives, with most yet to scale AI throughout their organizations. Merely one in 18 companies qualified as “high performers” based on McKinsey’s criteria—actively integrating AI and experiencing boosts of over 5% in earnings. The hitch lies in the effective incorporation of AI tools into workflows and operational structures. Data from the U.S. Census Bureau concerning firms of varying sizes indicate a decline in AI adoption, particularly among those with over 250 employees (Figure 3).

Thus, many AI firms are unlikely to achieve profitability, as prices erode due to competition from Chinese alternatives, while the costs associated with training and inference continue to rise due to their aggressive scaling strategies.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Business Trends and Outlook Survey (BTOS) 2023-2025. Notes: The U.S. Census Bureau conducts a biweekly survey of 1.2 million firms. Businesses are asked whether they have used AI tools such as machine learning, natural language processing, virtual agents, or voice recognition to facilitate goods or services within the past fortnight. See Torsten Sløk (2025b), https://www.apolloacademy.com/ai-adoption-rate-trending-down-for-large-companies/

The Ticking Time Bomb of Hyperscale Borrowing

AI companies cannot finance the necessary capital expenditures through revenue from subscribers or contributions from sovereign wealth funds. Therefore, these firms will resort to hyperscale borrowing from banks and investment-grade bond markets to fund their capital expenditures, laying the groundwork for the next debt crisis. This borrowing will create a ticking time bomb on the balance sheets of AI firms, as core capital expenditures involve specialized GPUs and servers that, due to relentless technological advancements, risk becoming economically obsolete within two to three years.

Nvidia exacerbates this issue by releasing new generation GPUs annually, with prices likely to decline. According to Nvidia’s latest Blackwell GPUs, new servers are necessary for implementation. For extensive use, entirely new data centers might need to be constructed, as these GPUs demand substantially more power and cooling. Consequently, the depreciation rate for the AI compute infrastructure is high, yielding short payback periods. “You’re investing in something akin to perishable goods,” economist David McWilliams aptly termed AI hardware “digital lettuce,” implying its inevitable obsolescence. Data servers and networking equipment have a functional lifespan of three to five years, with corresponding annual depreciation rates of 20% to 30%. These chips are purpose-built for training and executing generative AI models, tailored to specific architectures and software ecosystems from a handful of major providers like Nvidia, Google, and Amazon. Consequently, these chips form part of specialized AI data centers engineered for high power density, advanced cooling, and unique networking—a closed system optimized for scaling but challenging to repurpose.

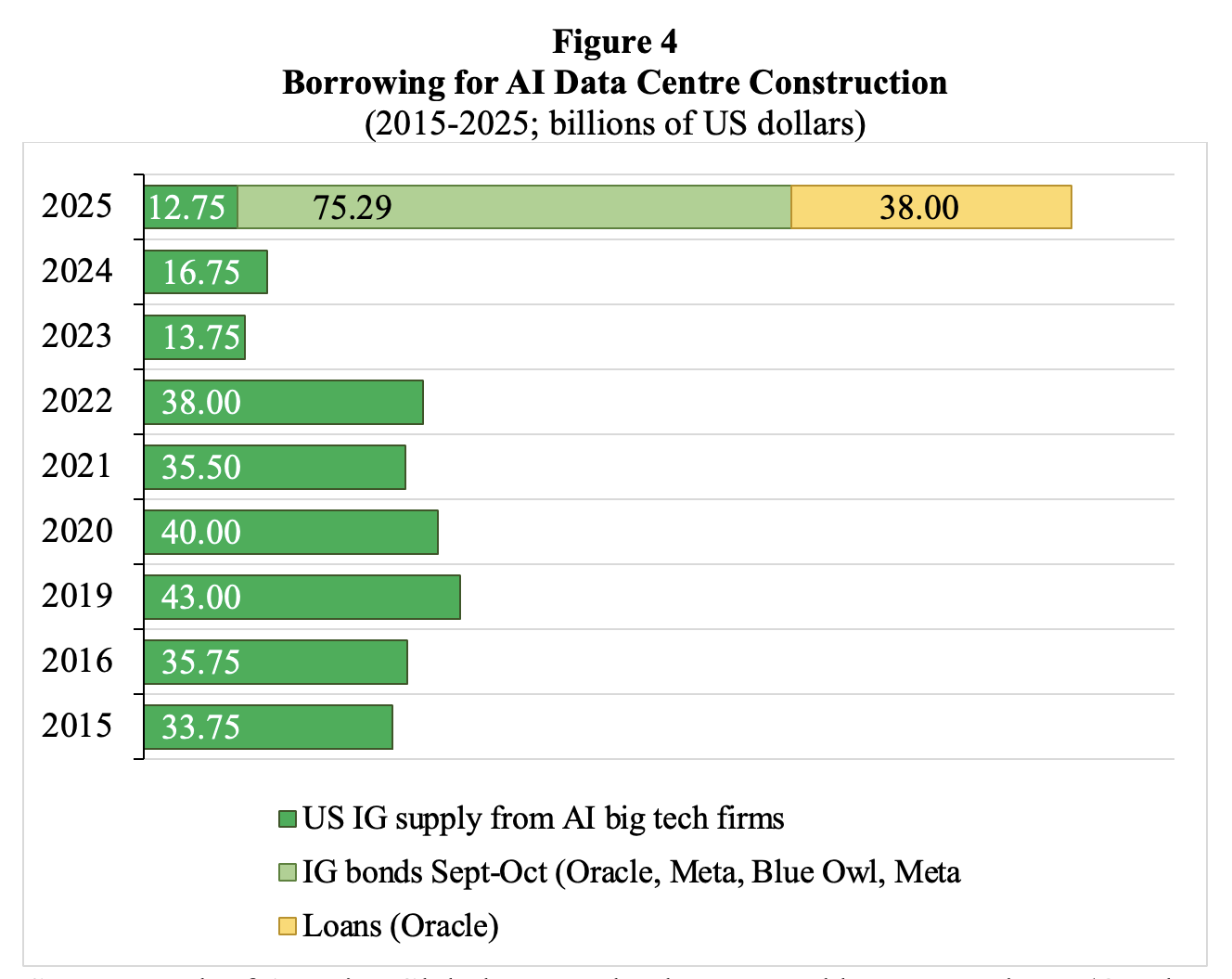

Figure 4 illustrates borrowing patterns for AI data-center construction. Investment-grade borrowing by major tech firms engaged in AI during September-October 2025 totaled $75 billion—compared to an average of $32 billion annually from 2015 to 2024. By October 2025, AI companies represented 14% of the American investment-grade bond market. Barclays estimates indicate that cumulative AI-related investments could reach over 10% of U.S. GDP by 2029, up from approximately 6% during the first half of 2025.

As OpenAI, Anthropic, and other startups continue to incur losses, they must fund most scheduled investments by selling stakes to investors and engaging in hyperscale borrowing from financial institutions and investment-grade markets. Ignoring numerous red flags—particularly concerning operating leverage and financial risk—many Wall Street players are desperate to claim a piece of the pie, often through off-balance-sheet Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs) from banks like JPMorgan Chase and Morgan Stanley as well as asset managers such as BlackRock and Apollo Global Management. This frenzied rush likely lays the groundwork for the next debt crisis (Fitch 2025).

Source: Bank of America Global Research; chart created by Lucy Raitano (October 31, 2025). Notes: IG = investment grade. Data concerning Blue Owl and Meta refer to a joint venture created by Blue Owl Capital to invest in a large-scale Hyperion data center project with Meta.

Exponential Growth in an Analogue World

Realistically, building the projected data center infrastructure over the next five years seems improbable (the typical timeline for most AI investors). Currently, it takes about two years to construct a hyperscale data center, but expect this timeframe to extend to seven years or more. Why? Suppliers from established industries must scale up production to accommodate this growth, and they will likely encounter workforce shortages, long waiting periods for power grid connections, material shortages, and regulatory hurdles—all of which will stretch the necessary timelines for building hyperscale data centers, as elaborated in the working paper.

FT Alphaville (2025) also highlights that the nature of AI-related power demand poses specific challenges (Wigglesworth 2025a). A recent report by Nvidia (2025) states:

“Unlike traditional data centers handling thousands of unrelated tasks, an AI factory functions as a cohesive synchronous system. During the training of a large language model (LLM), dozens of GPUs engage in intense computation cycles followed by data exchange, all operating in near-perfect unison. This results in a facility-wide power profile characterized by extreme, rapid load fluctuations. This volatility has been documented in collaborative research by NVIDIA, Microsoft, and OpenAI concerning power stabilization for AI training data centers. The research illustrates how synchronized GPU workloads can lead to grid-scale oscillations. A single rack’s power demand can fluctuate from around 30% utilization when idle to 100% usage within milliseconds. Providers must oversize components to manage peak currents rather than averaged loads, which can inflate costs and increase spatial requirements. When considered across an entire data hall, these extensive and rapid oscillations—amounting to hundreds of megawatts cycling in mere seconds—pose significant threats to utility grid stability, rendering grid connectivity a primary bottleneck in AI scaling.

AI Scaling is Running into Barriers

The primary strategy of leading AI firms—believing that Generative AI can be achieved by constructing more data centers and utilizing more chips—is already faltering. This scaling strategy is revealing diminishing returns. It appears flawed since generic LLMs are constructed not on sound, robust world models, but rather to maximize completion based on advanced pattern recognition (Shojaee et al. 2025). LLMs continue to make errors and produce hallucinations, especially when tasked beyond their training data.

Three years into the LLM evolution, AI expert Gary Marcus underscores why ChatGPT has not met expectations: “The results are disappointing due to the unreliability of the underlying technology. This has been evident from the beginning.” Generic LLMs are difficult to control; they struggle with reasoning; they fail to smoothly integrate with external tools; they frequently produce erroneous outputs; and they cannot match the performance of specialized models, which complicates aligning AI outputs with human requirements. “The reality is that ChatGPT hasn’t matured,” Marcus concludes.

Marcus further illustrates the performance of frontier LLMs through three benchmarks established by CMU professor Niloofar Mireshgalleh. The first benchmark involves a mathematical assessment suitable for resolution through substantial datasets. Not surprisingly, frontier LLMs demonstrate improved performance—albeit at the cost of extraordinary compute consumption. The second benchmark, centering on coding proficiency, has shown initial progress in outcomes, but now exhibits waning improvements, signaling diminishing returns. On the third benchmark—concerned with tasks demanding both theory of mind and privacy that are more difficult to manipulate—the frontier LLMs reveal slow and linear advancements, again requiring considerable financial and energy investment. In essence, advancements in performance for complex tasks lag significantly, shedding light on user dissatisfaction and presenting obstacles for widespread enterprise adoption.

While LLMs excel at generating plausible outputs, they are far less adept at delivering factual accuracy, especially when reasoning is involved. The tendency to hallucinate (as noted by Metz and Weise 2025) restricts the applicability of AI in critical sectors such as healthcare, education, and finance. The potential liabilities stemming from decisions made by autonomous, unsupervised AI tools are simply too significant for high-stakes scenarios—limiting the trust in and reliance on such technologies. More generally, LLMs should be perceived, as Bender and Hanna (2025) propose, as “machines merely extruding synthetic text.” “Like industrial plastic processes,” they describe, text databases are compelled through intricate machinery to create outputs that resemble communicative language, though devoid of intent or understanding. This paradigm extends to “generative” AI models that produce images and music; all can be categorized as “synthetic media machines” or substantial plagiarism devices, producing outputs that often replicate prior inputs. A large proportion of their outputs will amount to ineffective AI-generated material.

Ironically, the supply of ineffective AI outputs is poised to increase as a result of the lack of authentic training data, pushing LLMs to rely more heavily on artificial, AI-generated datasets—an alarming act of self-sabotage. As these models take in more flawed outputs, the chances of generating subpar results rise: the principle of “garbage-in, garbage-out” (GIGO) remains relevant. AI systems, trained on their outputs, gradually lose accuracy and diversity, leading to compounded errors across generations, producing distorted data distributions and irreversible performance issues. Veteran tech journalist Steven Vaughn-Nichols warns, “We’re heading to a point where we keep pouring resources into AI, only to reach a juncture where model collapse becomes apparent, and even the most indifferent CEOs cannot overlook AI’s failures.”

Conclusion

These four pivotal factors indicate that the AI scaling strategy will fail, likely leading to a burst of the AI data-center investment bubble. The inescapable downturn in the AI data center sector will inflict significant pain on the economy, although some viable technology and infrastructure may persist in the long term. Unfortunately, the unbridled avarice of major tech firms means that AI applications undermining labor conditions—within sectors like visual arts, education, healthcare, and media—will likely continue. Similarly, generative AI has already permeated military and intelligence contexts, ensuring its use for surveillance and corporate control. While the grand promises of the AI industry may fade, many detrimental applications of technology will remain.

The immediate economic harm may appear relatively minimal compared to the long-lasting effects of the AI hysteria. The continual oversaturation of ineffectual AI outputs, LLM-generated falsehoods, clickbait, disinformation, deepfake visuals, and a constant stream of low-quality machine-generated content—all produced under the guise of progress and wealth within the capitalist framework—will further weaken and contaminate trust in America’s economic and social structures. Ultimately, the significant costs—both direct and indirect—associated with generic LLMs will overshadow the limited benefits they offer.