“The bank is something more than men, I tell you. It’s the monster. Men made it, but they can’t control it.”

“The bank is something more than men, I tell you. It’s the monster. Men made it, but they can’t control it.”

– John Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath

Negative Carry

The practice of borrowing short-term funds and lending them long-term generally functions well in modern banking. As a customer, you’re not just a client; you play a crucial role in the banking process.

In simpler terms, banks reward you with a small percentage for the deposits in your checking and savings accounts, which you can access whenever needed. This forms the “borrowing short” aspect of their operations.

In return for your deposits, banks invest in longer-term assets like loans and bonds that yield returns over many years. If a bank earns 2 percent on these investments while paying depositors a fraction of that, it can profit from the difference, known as the net interest margin. It’s a straightforward way to generate income.

But when the Federal Reserve intervenes by lowering the federal funds rate to zero for a two-year stretch (from March 2020 to March 2022), thereby pushing yields to unprecedented lows, negative consequences can arise.

Over the past two years, consumers have faced rampant price inflation. Yet, this is just one aspect of the fallout from such monetary policy.

As the Fed began to raise rates in March 2022 to counteract inflation, the yield curve inverted, leading to a situation where short-term yields surpass long-term ones. Consequently, banks that relied on borrowing short to lend long suddenly found themselves in a difficult position, experiencing negative carry.

All might have turned out well for banks if their depositors had remained loyal. However, with Treasury Direct offering nearly 5 percent returns – without any brokerage fees – why would anyone keep excess funds in a bank for merely a fraction of a percent?

This raises an important question.

Answering the Call

Recently, customers of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) responded to this dilemma by withdrawing their deposits en masse. On March 9, SVB clients pulled over $1 million per second for a continuous ten hours, amounting to $42 billion, until the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) intervened and declared the bank insolvent.

This event was essentially a modern banking run, accelerated by the digital age.

SVB isn’t the first bank to collapse due to the risks of borrowing short and lending long, nor will it be the last. Following SVB, Signature Bank also failed, and Credit Suisse required a bailout from the Swiss National Bank. At this pace, more banks may soon meet a similar fate.

What we truly care about isn’t which banks collapse but the repercussions that follow. In SVB’s case, a bailout—beyond FDIC protections—is forthcoming through a newly established program called the Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP).

Essentially, the BTFP is a euphemism for socializing losses. Regulators may deny that it constitutes a bailout, emphasizing that taxpayers aren’t directly footing the bill. However, if you hold a bank account, you will likely bear the costs via fees and surcharges imposed by banks to compensate for SVB depositors. Is that equitable?

Should you shoulder the costs for California Governor Gavin Newsom’s wineries, billionaire Mark Cuban’s drug company, or any other wealthy individuals who mismanaged their risks?

Further, what will become of SVB and other failing banks? Will the FDIC liquidate them to major banks like JPMorgan Chase, similar to the Washington Mutual acquisition in 2008?

Government bailouts and banking consolidations don’t inherently ensure safer banking practices. Instead, they distribute risk across the entire financial landscape, akin to scattering mustard seeds on a hillside. This invariably leads to more severe banking crises in the future.

It also breeds societal unrest and dissatisfaction. But for what purpose?

The repetitive merging and consolidating of banks can have dire implications. To illustrate this, let’s delve into a historical example of significant bank failure.

Epic Bank Failure

In 1820, Salomon Mayer von Rothschild (1774-1855) founded S M von Rothschild in Vienna, which was then the capital of the Austrian Empire.

Upon his death in 1855, his son, Anselm von Rothschild (1803-1874), established Credit-Anstalt, which grew to become the largest bank in Eastern Europe before World War II.

Credit-Anstalt managed assets and accepted deposits from throughout Europe, but in 1931, it collapsed at a critical juncture.

The bank’s downfall correlated directly with the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, a U.S. initiative that raised tariffs on over 20,000 imported goods, crippling Europe’s economy and leading investors to withdraw their investments from the bank.

The failure of Credit-Anstalt prompted Austria to abandon the gold standard, triggering a domino effect throughout Europe; Germany followed, then Great Britain, and ultimately the United States in 1933.

This bank’s failure was a catalyst for the onset of the Great Depression, but the story spans beyond Credit-Anstalt’s collapse; it lies in the events leading up to that moment.

As the Federal Reserve initially pushed banks to seek returns in long-term investments, only to later raise short-term interest rates, these institutions find themselves facing an unprecedented challenge. More banks like SVB are likely to emerge in the coming weeks.

A series of bailouts and bank consolidations may create a scenario reminiscent of the Credit-Anstalt catastrophe. The SVB bailout, including its connections to individuals like Gavin Newsom, sets a troubling precedent.

Forced Mergers

Following World War I, as the Austro-Hungarian Empire disintegrated, Credit-Anstalt continued providing commercial, investment, and savings services to clients from the former empire and other European cities. Its shares traded on eleven exchanges, including New York.

Through forced mergers aiming to rescue other faltering banks, Credit-Anstalt grew into the largest bank in Austria. While these mergers may have seemed practical, they were far from wise, as they didn’t always yield beneficial outcomes.

This consolidation created a bank that overshadowed all other Austrian banks combined, concentrating the losses of the country’s industries into one substantial institution.

Over time, Credit-Anstalt’s balance sheet surpassed the extent of the government’s expenditures, with about 70 percent of Austria’s corporations relying on its services.

By 1925, the bank’s equity had dwindled to just 15 percent of its 1914 value, and its debt-to-equity ratio soared from 3.64 in 1913 to 5.68 by 1924, reaching a staggering 9.44 by 1930.

The rapid growth in Credit-Anstalt’s size resulted from loans made to businesses within the former Austro-Hungarian Empire, financed primarily through short-term borrowing from Great Britain and the United States.

However, these short-term loans created a precarious situation; any failure to renew could lead to the bank’s demise. The ramifications of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act ultimately toppled their entire credit structure.

On May 11, 1931, Credit-Anstalt announced significant losses that exceeded half its capital, triggering a legal definition of failure under Austrian law. This revelation incited panic and led to a wave of withdrawals from Austrian banks.

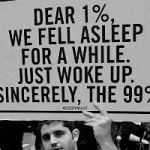

Occupy Wall Street Redux

The crisis that ignited in Austria quickly spread across Europe, reaching Great Britain, which abandoned the gold standard on September 21, 1931, after depleting its gold reserves from £200 million to just £5 million.

Within months, twenty-five countries followed suit, either depreciating their currencies against the U.S. dollar or leaving the gold standard altogether. By the end of 1931, the Great Depression had truly gone global.

In April 1933, FDR removed the U.S. from the gold standard, confiscated citizens’ gold, and devalued the dollar, leaving everyday people, such as workers, savers, and taxpayers, at a disadvantage.

This pattern was mirrored during the 2008-09 financial crisis when the public suffered harsh consequences while bankers received substantial bonuses.

During that time, widespread social unrest erupted, leading to movements like Occupy Wall Street. The recent bailout of SVB depositors, above FDIC limits, is reminiscent of those past grievances.

Indeed, Governor Gavin Newsom’s wineries received financial support, as did Mark Cuban’s drug company, along with many other wealthy elites who mismanaged their affairs.

This begs the question: should student loans also be forgiven? Should mortgage and credit card debts be canceled? Should laid-off Google employees receive bailouts to maintain their comfortable lifestyles?

These inquiries may seem ridiculous, but they highlight the absurdity of bailing out wealthy depositors while further consolidating the banking industry. What if major banks like JPMorgan Chase or Bank of America were to fail?

These daunting possibilities are what bank bailouts and consolidations bring to the forefront.

After decades of indulgence followed by neglect, America appears headed for a total financial, economic, and societal crisis. The signs are clear; the implications are palpable.

First stop: a renewed call to Occupy Wall Street.

In conclusion, ensuring your financial security through the ownership of physical gold and silver has never been more crucial.

[Editor’s Note: In turbulent times, the global elite often redirect public discontent toward grand causes. Is there a hidden agenda behind tensions with China? Are you financially prepared for uncertainties? Answers to these pressing issues can be found in a detailed Special Report titled, “War in the Strait of Taiwan? How to Exploit the Trend of Escalating Conflict.” You can access it for less than a penny.]

Sincerely,

MN Gordon

for Economic Prism