In an era where data is paramount, this article from Global GeoPolitics closely examines how pivotal African nations like Nigeria, Kenya, and Rwanda have inadvertently compromised their sovereignty through agreements concerning citizen tax and health data with foreign entities. These arrangements transcend mere technical assistance and signify a significant shift in control over vital national assets.

According to a detailed analysis conveyed via email:

Drawing on insights from independent analysts, legal scholars, and historical precedents, the report illustrates how data now mirrors the functions of taxation and population registers once utilized during colonial times. It outlines the long-term implications for sovereignty, security, and democratic accountability and asserts that these agreements represent a critical structural shift rather than isolated policy mistakes.

The dangers of these decisions become more apparent when considering recent evidence of how the same data companies operate in active conflict areas. An Associated Press investigation revealed that artificial intelligence systems developed by Microsoft and OpenAI were utilized in Israeli military targeting operations in Gaza and Lebanon, marking a significant instance of commercial AI being used in live warfare. These systems depended on extensive data collection, predictive modeling, and pattern analysis derived from civilian information channels. The findings underscore how population data, once integrated into security frameworks, can be redirected for surveillance, targeting, and life-or-death decisions without public oversight. By transferring tax, health, and biometric data to foreign partners, African governments are placing comprehensive population profiles into systems already proven to have military applications. Control over this data not only influences economic planning or healthcare delivery but also determines how populations can be mapped, categorized, and engaged during political crises, civil unrest, or foreign intervention. The Gaza case underscores that assurances of benign data use become irrelevant once such information enters intelligence systems governed outside the control of affected citizens.

Moreover, there exists a widely held belief that China’s significant economic investments in Africa have substantially diminished U.S. and European influence. However, the often-overlooked role of Western powers in overseeing and extracting sensitive information about citizens in major African countries indicates that the U.S. and former colonial nations still wield considerable power.

Originally published by Global GeoPolitics

Data colonialism on the African continent has shifted from being a theoretical concern to formal national policy through binding agreements made without public consultations, parliamentary oversight, or adequate legal protections for citizens. Nigeria’s memorandum of understanding with France on tax administration data and Kenya and Rwanda’s health data-sharing accords with U.S. agencies represent a pattern of foreign control over sovereign information systems. These arrangements signify the transfer of strategic national resources rather than mere technical cooperation. Historical lessons from former colonies illustrate that control over taxation, health records, and population data has often been a prelude to more profound forms of oppression, even when formal sovereignty appeared unaffected.

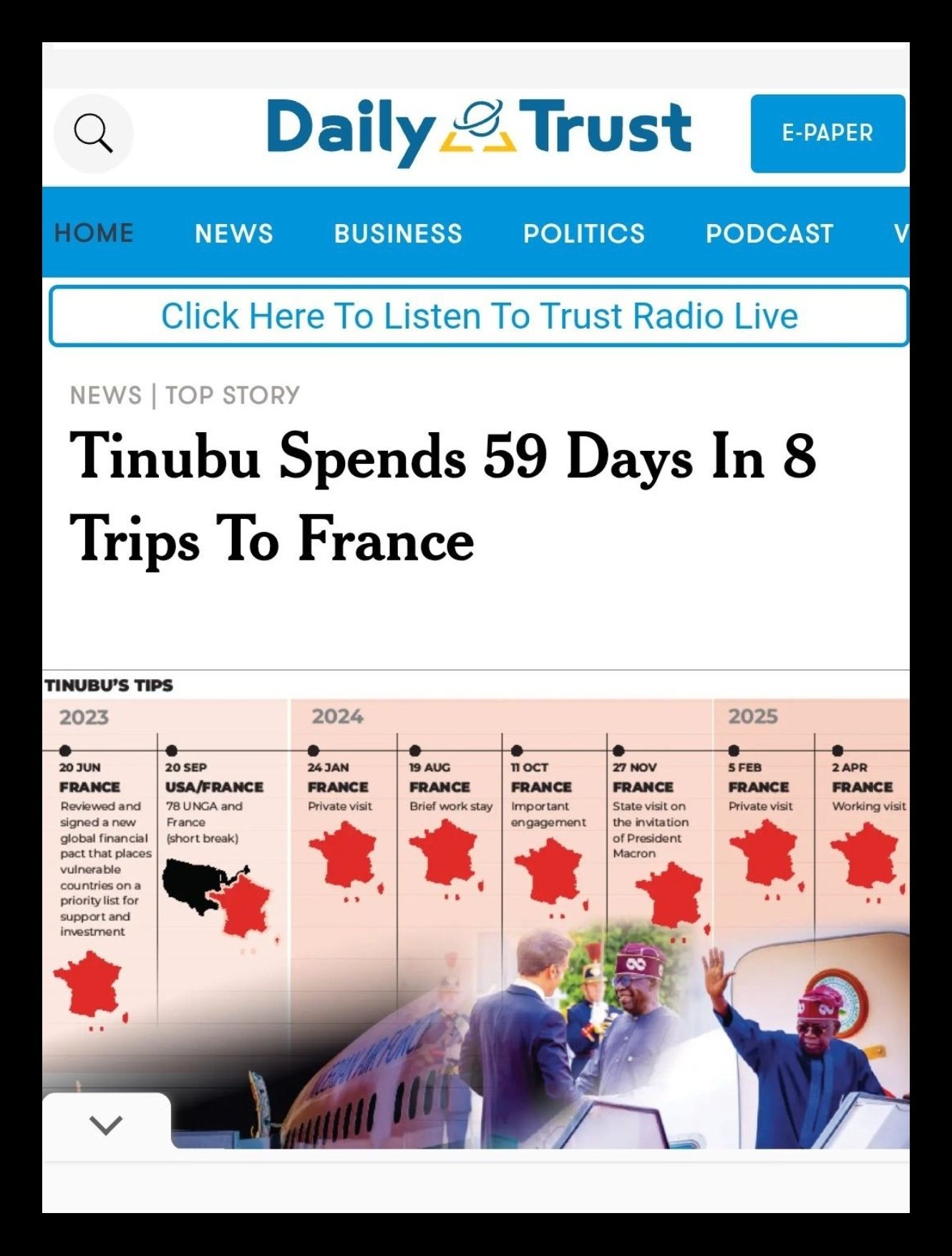

Nigeria’s accord with France centers around automated compliance systems, AI-driven audits, and data analytics for tax administration. While French officials tout it as mutually advantageous, the evident structural imbalance persists. Although France relinquished direct colonial power in West Africa, it has retained expertise in fiscal extraction, population monitoring, and administrative enforcement. Tax data can disclose income distribution, consumption trends, business structures, geographic movements, and political vulnerabilities. Economic historians like Walter Rodney have emphasized that taxation systems underpinned colonial administration, enabling metropoles to extract value without constant military enforcement. Modern digital tax systems replicate this function on a far grander scale and with increased accuracy.

Legal experts concerned with data sovereignty contend that aggregated datasets retain significant strategic sensitivity, even when individual records are anonymized. Professor Teresa Scassa from the University of Ottawa has indicated that aggregated data can accurately recreate behavioral and economic trends, particularly when combined with additional datasets. Once such information is transferred, recipient countries can gain lasting leverage over fiscal policy design, enforcement thresholds, and revenue projections. While Nigerian officials have asserted that raw taxpayer data will remain within national borders, cross-border analytics necessitate data visibility, modeling access, and algorithmic training inputs. Control incrementally shifts through reliance on foreign technical infrastructure and expertise.

Similar reasoning applies to Kenya and Rwanda’s healthcare data agreements with U.S. agencies, though framed as public health partnerships and biomedical innovations. Health data stands as a nation’s most extensive intelligence asset, encompassing genetics, disease distribution, medication responses, mental health patterns, and demographic vulnerabilities. Critics of bio-colonialism, including Dr. Vandana Shiva, warn that the extraction of genomic and health data permits pharmaceutical monopolies and fosters long-term dependency. African populations risk being reduced to research subjects while value creation occurs elsewhere, shielded by intellectual property laws enforced through international trade agreements.

These agreements were enacted without informed consent from citizens or open legislative discussions. Constitutional experts like Kenya’s Patrick Lumumba argue that consent cannot be implied through executive decision-making regarding fundamental rights related to bodily autonomy and privacy. The data protection frameworks in these countries remain underdeveloped, particularly concerning biometric, genomic, financial, and geolocation data. Legal advocates in Nigeria have alerted lawmakers that tax and GPS data did not receive explicit classification as sensitive national security assets. The inaction in Parliament enabled executive bodies to proceed under international pressure.

India serves as a cautionary example rather than a model for Africa. Rajiv Malhotra’s extensive research on digital colonization illustrates how Indian data assets were surrendered to foreign platforms under the banner of innovation and progress. Indian labor contributed to developing AI systems, yet their ownership, governance, and profit delineations remained external. Domestic startups were subsumed by multinational enterprises as the nation depended on foreign infrastructures for digital public utilities. While Indian policymakers maintained flags and constitutions, they lost control over information flows, cultural narratives, and behavioral influence. African nations are now on a similar trajectory, progressing swiftly yet with diminished institutional resistance.

The implications extend beyond economic realms into the sphere of political control. Researchers Nick Couldry and Ulises Mejias describe data colonialism as the appropriation of human existence through quantification, resulting in asymmetrical power dynamics akin to historical imperial structures. Behavioral data can empower external entities to steer elections, social movements, consumer behavior, and public opinion without overt coercion. Military intervention becomes superfluous when information systems successfully mold perceptions and compliance. Events such as the Benin coup and the broader instability in the Sahel illustrate how external powers maintain influence through select elites instead of relying on popular mandates. In this scenario, leaders act as administrative intermediaries rather than true representatives of their people.

U.S. government documents increasingly categorize health, technology, and data collaborations as integral to national security strategies. Former intelligence officials have remarked that data has become the new strategic resource, supplanting oil and minerals. African healthcare datasets feed AI systems utilized for military logistics, population modeling, and predictive governance. Professor Shoshana Zuboff’s exploration of surveillance capitalism highlights how data extraction consolidates power while undermining democratic accountability. African nations lacking bargaining strength trade perpetual data access for temporary funding, technical assistance, or political backing.

Initiatives from the United Nations and the World Economic Forum under Agenda 2030 advocate for digital identity systems, interoperable health records, and transnational data frameworks. Though the official language promotes inclusivity and efficiency, governance often functions outside of national jurisdictions. Political economist Quinn Slobodian elucidates how global governance structures bypass democratic procedures in favor of technocratic control. African governments adopt these frameworks without public consensus, often under pressure from debt obligations or diplomatic maneuvers. Citizens inherit digital systems designed, governed, and monetized externally.

Modern recolonization manifests through standards, platforms, and dependencies rather than through direct occupation. Control over data infrastructure influences future industrial capabilities, defense preparedness, and political autonomy. States unable to disengage from foreign systems forfeit their ability to function independently in crises. Countries like China and Russia recognized this threat early and established stringent data localization, platform regulations, and sovereign cloud frameworks. In contrast, African nations remain fragmented, vulnerable, and reliant on external assurances that history has repeatedly shown to be unreliable.

Independent African economists such as Samir Amin cautioned that peripheral integration into global systems seldom yields development absent internal capacity building. Data extraction mirrors the patterns of raw material export, relegating value-added processes to foreign soil. AI developed using African data will produce products sold back to African governments at monopolistic prices. This dependency accelerates while sovereignty erodes gradually, rarely inciting immediate public dissent since the repercussions unfold slowly over time.

Political accountability diminishes as leaders negotiate away strategic assets without electoral repercussions. Executive power expands while citizen oversight contracts. Digital systems deployed without consent mold populations into compliance through dependency on services. Non-participation becomes impractical when access to healthcare, tax systems, banking, and identification hinges on digital involvement. Epistemic control supplants overt repression, resulting in what sociologists term managed consent.

After centuries of slavery and exploitation by the West, it appears that the lessons of the past have yet to resonate within African minds. The risks of these contemporary decisions become stark when examining evidence of how the same data firms engage in active conflict zones. The Associated Press confirmed that AI systems developed by Microsoft and OpenAI were embedded in Israeli military operations targeting Gaza and Lebanon, marking a pivotal instance of commercial AI employed in actual warfare. These systems relied on extensive data input, predictive analytics, and pattern analysis extracted from civilian information streams. This outcome illustrates how population data, once integrated into security protocols, can be repurposed for surveillance, targeting, and lethal decision-making devoid of public accountability. African governments that share tax, health, and biometric data with foreign partners are consequently placing vast population profiles into systems demonstrated to facilitate military action. Control over such data influences not only economic strategy and healthcare provision but also the potential to map, categorize, and act against populations during political upheavals, civil discord, or external interference. The Gaza incident reminds us that promises of responsible data use hold little significance once data is ensconced within comprehensive intelligence frameworks that operate outside the purview of those affected. The rapid deployment of AI technologies for lethal purposes underscores the existential risks they present; African leaders, however, often overlook these threats, believing that anonymizing data renders it immune to re-identification. This may well be one of the myths they have been led to believe.

African nations must act promptly to assert their data sovereignty through constitutional safeguards, legislative oversight, and the development of domestic technical capabilities. Inaction would yield a future governed by algorithms designed externally. Historical empires extracted resources until resistance emerged; now, digital empires capture behavior, identity, and decision-making processes, leaving little room for reversal as these systems mature. African governments must halt all cross-border data-sharing agreements pending public transparency, parliamentary examination, and constitutional review. National data protection regulations should categorize financial, biometric, genomic, and geolocation data as strategic assets with stringent localization requirements. Building domestic capacities should replace dependency on foreign technical frameworks through regional collaboration and independent infrastructure initiatives. Citizens should be granted enforceable rights concerning data usage, withdrawal, and recourse. For independence to hold meaning, sovereignty must extend beyond physical borders into digital and epistemic dimensions.