In this enlightening examination, financial expert Satyajit Das critiques the burgeoning field of artificial intelligence (AI) and its questionable hype. His insights highlight the concerns surrounding the technology, its financial feasibility, and the potential risks involved. This discussion calls for careful consideration and widespread dissemination among readers.

By Satyajit Das, a former banker and author of numerous technical works on derivatives and several general titles: Traders, Guns & Money: Knowns and Unknowns in the Dazzling World of Derivatives (2006 and 2010), Extreme Money: The Masters of the Universe and the Cult of Risk (2011), and A Banquet of Consequence – Reloaded (2016 and 2021). His latest book is on ecotourism – Wild Quests: Journeys into Ecotourism and the Future for Animals (2024). This is an expanded version of a piece first published on 4 November 2025 in the New Indian Express print edition.

AI follows the familiar boom-and-bust pattern first identified in 1837 by Lord Overstone. This cycle includes phases of dormancy, enhancement, confidence, prosperity, excitement, overtrading, upheaval, stagnation, and distress.

Three main concerns arise regarding AI.

First, there is skepticism about its underlying technology. Generative AI (GenAI), the latest evolution in this realm, utilizes large language models (LLMs) trained on vast datasets to generate text and imagery. Aiming for the elusive “singularity,” where machines might exceed human intelligence, proponents envision a transformative merging of humans and machines.

However, LLMs depend on vast amounts of data, which established companies in sectors like search engines and social media can leverage from their repositories. This data often includes unauthorized scraping from online resources, sometimes involving private data, leading to legal disputes over access and privacy rights. Consequently, many AI models are hampered by incomplete and poorly cleaned data.

Despite advancements in computational capabilities, GenAI frequently falters in simple factual tasks. Errors, bias, and misinformation in its training datasets lead to inconsistencies. While AI models can interpolate responses based on existing data, they struggle with extrapolation. They are akin to rote learners, challenging when presented with novel problems, and their ability to navigate dynamic environments independently is still questionable. Some cognitive scientists argue that merely scaling up LLMs, which rely on sophisticated pattern-matching, will ultimately disappoint. The claimed advancements in this field are hard to measure due to vague benchmarks.

Supporters overlook that LLMs do not possess reasoning abilities; instead, they function as probabilistic prediction engines. By analyzing existing data, they cannot generate genuinely new content. As they exhaust available sources, further scaling results in diminishing returns. Rather than representing fully generalizable intelligence, generative models resemble content regurgitators that struggle with accuracy and coherent reasoning.

AI can automate specific labor-intensive activities, including data-driven research, journalism, travel planning, coding, and some medical diagnostics. However, its grand ambitions may remain unfulfilled. While predictions of medical breakthroughs have fallen short, earlier machine learning models in pattern recognition, built before the OpenAI era, still deliver benefits.

For now, GenAI, often more of a marketing catchphrase than a technical reality, serves primarily as an expensive novelty for simple applications, while facilitating scams and misleading practices – the “unfathomable in pursuit of the indefinable.”

Secondly, the financial returns from AI may not materialize as anticipated. Expenditures on AI technologies are projected to reach between $5-7 trillion by 2030. The valuation of AI startups surged to $2.30 trillion after the latest funding round, up from $1.69 trillion in 2024, and a mere $469 billion in 2020. However, AI’s actual capacity to generate profit and investment returns remains questionable.

To merely cover current investments in infrastructure, rapidly depreciating chips, and operational costs, revenues must climb over 20-fold from the current $15-20 billion annually. Projections suggest that revenues exceeding $1 trillion might be necessary to achieve acceptable returns. Despite being among the most widely used software globally, Microsoft’s Windows and Office generates less than $100 billion in combined revenue, and only about 5 percent of its 800 million users currently pay to use ChatGPT. Microsoft’s CEO sparked debate by stating that AI has yet to deliver a profitable, groundbreaking application comparable to email or Excel.

The prevailing hope is that productivity gains will finance AI investments through increased corporate profits. However, 95 percent of corporate GenAI pilot projects have failed to drive revenue growth. Following layoffs of hundreds of employees to replace them with AI, many companies were later compelled to rehire due to the technology’s inadequacies. Interest in corporate AI is already showing signs of stagnation .

Monetization of AI is fraught with further uncertainties. Several Chinese companies, including DeepSeek, Moonshot, and Bytedance, have created more affordable models that challenge the capital-intensive strategies of their Western counterparts. China’s focus on open-source designs threatens the revenue streams of those heavily invested in proprietary technologies. Additional constraints may arise from the essential supplies of electricity and water.

Currently, AI firms are also burning through cash rapidly. In the first half of 2025, OpenAI, the owner of ChatGPT, generated $4.3 billion in revenues while incurring $2 billion in sales and marketing expenses and about $2.5 billion in stock-based compensation, leading to an operating loss of $7.8 billion.

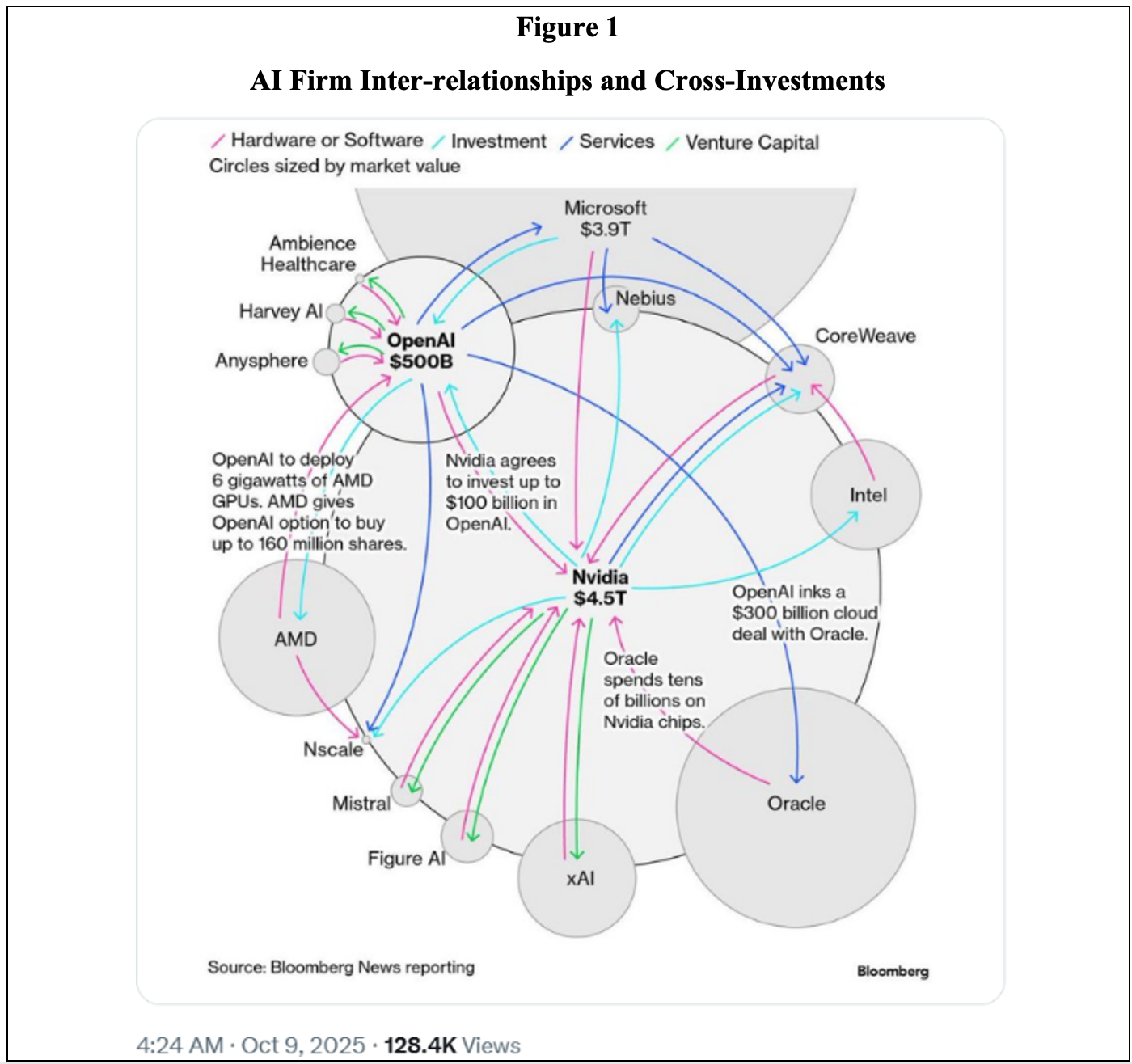

Thirdly, financial circularities reminiscent of the dot-com bubble are emerging. CoreWeave, a company capitalizing on the AI boom, purchases highly sought-after graphic processors and rents them out. As Nvidia, a significant investor, supplies the majority of its revenue, concerns about CoreWeave’s accounting practices and robust debt levels have arisen.

In 2025, Nvidia, the backbone of this boom, agreed to invest $100 billion in OpenAI, which in turn planned to purchase comparable amounts in GPUs. OpenAI also expressed intentions to invest in chipmakers like AMD and Broadcom, along with making arrangements with Microsoft. Figure 1 illustrates these intricate interrelationships.

Figure 1

AI Firm Inter-relationships and Cross-Investments

These complex relationships pose inherent risks. They complicate ownership structures and can create conflicts of interest. It’s unclear how such commitments will be financed or executed. OpenAI’s capability to fulfill these investment commitments hinges on continuous access to fresh capital from investors, as it currently lacks the resources to meet many of its long-term obligations.

These financial dealings may distort overall performance. Selling firms record sales and profits, while treating the funding as investments. Purchasers amortize their costs over several years. Given Nvidia’s frequent upgrades to chip architecture, depreciation periods beyond five years seem overly optimistic. Consequently, inflated earnings can artificially boost stock prices, contributing to a dizzying financial cycle.

The AI bubble, with its ever-widening divide between projected expectations, investment volumes, and revenue potential, uncannily echoes the late 1990s. However, its scale is significantly larger. Investment levels could be 17 times those seen during the dot-com bubble, and four times the 2008 subprime housing crisis.

Proponents of AI dismiss any signs of excess, claiming this cycle is distinct because it is predominantly funded by equity capital. In reality, a substantial portion is financed through debt, with AI-related investments totaling around $1.2 trillion or 14 percent of all investment-grade debt.

The investment pattern is notably interesting. Hyperscalers—companies managing extensive data centers that provide on-demand cloud computing and related services, including Microsoft, Meta, Alphabet, and Oracle—are significant funders, alongside venture capitalists. These companies currently allocate approximately 60 percent of their operating cash flow to capital expenses, most of which support AI projects. This is often augmented by borrowing, relying on robust credit standings to finance their endeavors. Furthermore, there’s an evident trend towards private credit funding, projected at around $800 billion over the coming two years, with a total of $5.5 trillion by 2035. With these lenders displaying high-risk tolerance, the financial discipline applicable to these loans remains questionable.

These large corporations are now acting as lenders themselves, financing AI startups with uncertain prospects by borrowing extensively. This exposure raises concerns, as investors and lenders assume they are backing robust enterprises while they are often heavily invested in speculative AI ventures. For instance, Microsoft’s share of OpenAI’s losses exceeds $4 billion in the last quarter, amounting to approximately 12 percent of its pre-tax earnings.

Oracle’s situation serves as a cautionary tale. The company’s shares soared by 25 percent after announcing a deal to provide cloud computing services to OpenAI. However, as the necessary data centers currently do not exist, Oracle will need to borrow extensively to construct them, thereby exposing itself to considerable risk with OpenAI. As of December 2025, investor apprehension was palpable. Given Oracle’s net debt exceeding $100 billion, anticipated borrowing to finance the data centers could further exacerbate risk, potentially warranting a credit rating downgrade from its current BBB rating. The decline in its share price has reverted to levels seen before the OpenAI announcement. While Microsoft, Meta, and Amazon may have stronger financial positions, their risks are not dissimilar.

The broader economic implications of the AI boom are notable. AI enterprises contribute to approximately 75-80 percent of US stock returns, earnings growth, and 90 percent of capital expenditure growth. The sector has added around 40 percent, effectively boosting the US economy by a full percentage point in 2025. A downturn in AI would directly impact the broader economy, leading to financial instability due to banks’ and financial institutions’ exposure to the AI sector. It is possible some tech firms may require bailouts reminiscent of those extended to Intel, along with support for financial institutions to prevent economic collapse.

Investors have increasingly convinced themselves that the real risk lies in underinvestment rather than overinvestment. Amazon founder Jeff Bezos famously calls it a “good kind of bubble,” asserting that current expenditures will yield long-term benefits that dramatically enhance societal welfare. Investors, however, should exercise caution. During the telecom and fiber-optic cable bubble of the ’90s, there was a significant overestimation of capacity demand. Today, the proportion of utilized fiber-optic capacity, much of which was installed during that boom, is only about 50 percent, with global network utilization averaging just 26 percent.

Investors think they can minimize risks by steering clear of direct exposure to AI companies, opting instead to back firms like Nvidia that provide the foundational technologies for this revolution. The example of Cisco, which enjoyed a similar investment narrative in the heady days of the 1990s, serves as a valuable benchmark. Cisco briefly became the world’s most valuable company due to the widespread assumption that its networking products would be essential to the Internet’s growth. While its financial performance has remained relatively stable, investors in Cisco experienced significant losses during the 2000 market crash, with the stock only recovering its previous value after 25 years.

The aftermath of the dot-com boom saw Microsoft, Apple, Oracle, and Amazon experiencing declines of 65, 80, 88, and 94 percent, respectively, taking 16, 5, 14, and 7 years to return to their 2000 peak values. This slowdown necessitated government intervention and historically low interest rates to sustain economic activity, eventually leading to the 2008 housing crisis.

Despite current optimistic projections, it would be surprising if this cycle concluded differently.

© Satyajit Das 2025 All Rights Reserved