Armed conflict in Africa is often interpreted through various lenses, including the remnants of colonialism, interference from foreign powers, the rise of transnational jihadist movements, or, in the most simplistic terms, as tribal warfare. While each narrative contains some truth, none alone adequately addresses the complexity, persistence, and diversity of conflicts across the continent. This oversimplified discourse is not only morally appealing and politically expedient but also strategically ineffective.

The remarkable aspect of wars in Africa is not merely their occurrence but their variety. Conflicts in regions such as the Sahel, Sudan, eastern Congo, Ethiopia, Somalia, and Nigeria differ significantly in terms of their dynamics, participants, and developmental trajectories, despite sharing superficial similarities like weak governance, porous borders, or external intervention. Viewing these wars through a singular lens—be it colonial legacy, ethnic strife, terrorism, or climate stress—obscures more than it clarifies.

A more nuanced approach starts with an often-overlooked premise: Africa’s conflicts are the result of multiple, interrelated causes that manifest in varying degrees. The effects of colonialism are significant, yet they do not unfold in isolation. Factors such as post-colonial governance, political economy, demographic pressures, dynamics within the security sector, resource rents, and external shocks all converge to create distinct conflict patterns. Wars endure not because Africa is ensnared in an unending historical cycle but due to the strain placed on fragile political systems from numerous simultaneous directions.

A Typology of Contemporary African Conflicts

Any comprehensive analysis must begin with a clear description. What follows is not a complete list but a structured overview of the primary conflict types currently influencing the continent.

- State fragmentation and elite power struggles typify conflicts in Sudan, South Sudan, Libya, and the Central African Republic. In these situations, the central concern is not societal breakdown but the competition among armed elites for state resources. Here, violence serves as a means of negotiation within a fragmented sovereignty.

- Insurgency in weak peripheral states characterizes much of the Sahel and northern Mozambique. In these areas, jihadist movements are better understood as opportunistic forces that exploit marginalization, predatory security forces, and the lack of effective governance in rural regions.

- Protracted war economies dominate the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, where violence persists not due to the impossibility of victory but because conflict has become a means of political and economic organization. Armed groups act as extractive entities within regional and global markets.

- Center-periphery and identity-based state crises are evident in Ethiopia and Nigeria, where the state remains intact but its legitimacy is challenged by ethnic, regional, or religious factions. These conflicts revolve around political contests over inclusion and power distribution, rather than failures of state existence.

- Near-complete state substitution, as seen in Somalia, reflects a different scenario: the collapse of central authority followed by the rise of alternative governance structures rooted in clan alliances, commerce, and coercion.

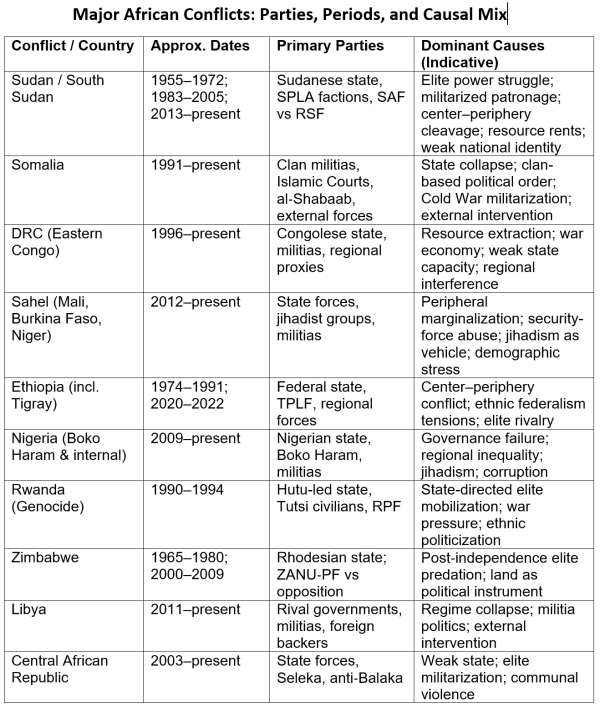

This diversity alone dispels any notion that Africa’s wars arise from a common cause. They do not share a singular origin, but rather interrelated pressures that vary in intensity. The factors that contribute to conflict, as illustrated in the table below, represent the multiple, interacting influences shaping these situations rather than definitive explanations for any single case.

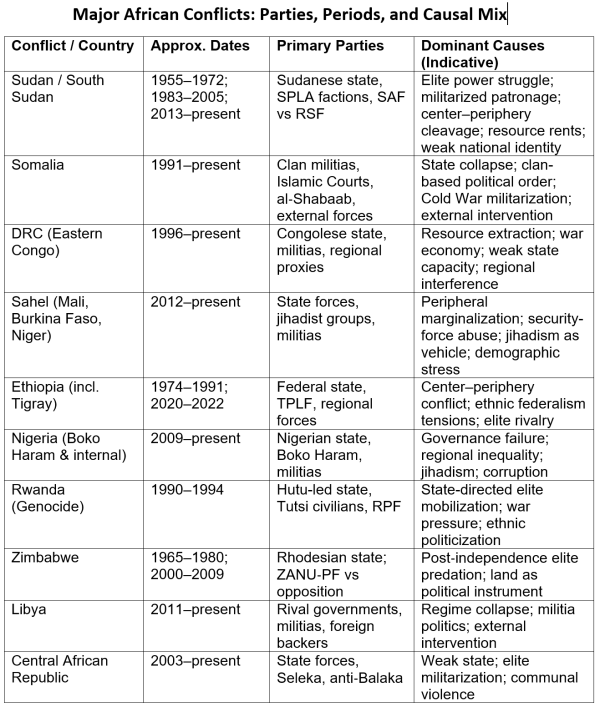

The human cost of these conflicts has been staggering. In many instances, the majority of casualties arise not from combat itself but from displacement, famine, and the deterioration of essential governance—consequences that linger long after the immediate violence has subsided.

Refugee camp in Somalia

Proportional Causation and the Limits of Colonial Explanations

Colonialism has undeniably influenced Africa’s political landscape, institutional frameworks, and extraction methods. However, it does not provide a uniform explanation for the divergent outcomes seen in different countries post-independence.

Taking Zimbabwe as an example, although the Rhodesian regime was marked by brutality and exclusion, it did not leave behind a structurally ungovernable state in 1980. Zimbabwe inherited operational institutions, viable agriculture, and educated elites. Its subsequent decline can be attributed primarily to political choices made after independence—such as elite exploitation, violent land seizures to maintain regime power, and the intentional dismantling of institutional capacity. Colonialism set the stage, but it did not dictate the script.

Conversely, the Hutu-Tutsi genocide in Rwanda illustrates a tragic example where colonial administration exacerbated ethnic divisions and grievances, yet the genocide itself was not an inevitable result of decolonization. Instead, it was a calculated, state-driven project occurring amidst war, regime vulnerability, and international neglect. Colonialism informed identity-related tensions; post-colonial leaders manipulated these dynamics for their purposes.

In the case of Somalia, the colonial legacy offers minimal insight into its post-1991 evolution. The nation’s disintegration and reformation were driven by clan dynamics, Cold War militarization, and the lack of a unifying national political settlement. Viewing Somalia solely through the lens of colonial failure overlooks the fact that a non-state governance structure was emerging—one that external forces consistently disrupted.

The lesson here is not to dismiss colonialism’s impact but to appreciate how causes operate in varying degrees. Fixating on a single factor as universally decisive guarantees analytical misunderstanding.

Why Misdiagnosis Persists

If African conflicts are as diverse as suggested, why are they so frequently misunderstood? A significant part of the answer lies in the structural limitations of U.S. foreign policy. The American diplomatic framework was designed to manage relations among bureaucratic states rather than complex political systems where power is dispersed through informal networks, armed factions, and negotiated legitimacy. Elections, constitutions, and formal institutions are often mistakenly seen as the primary sources of authority.

While some diplomats and analysts grasp these complexities, the United States has never built a robust institutional capacity to translate that understanding into actionable policy. Insights tended to remain individualistic and fleeting, while decision-making leaned towards ideological simplifications: Cold War anti-communism, post-Cold War democratization, and post-9/11 counterterrorism. Each of these frameworks oversimplifies reality in different ways, prioritizing action over a genuine understanding.

Somalia as the Textbook Failure

Somalia exemplifies why singular narratives often fall short. For over thirty years, external actors have viewed the country as merely a humanitarian crisis, a failed state, a terrorism hotspot, and a testing ground for state-building efforts—all simultaneously. Each perspective has justified various interventions, yet none have adequately addressed the political reality emerging after the collapse of central authority: a fragmented but functioning order based on local governance, commerce, and coercion.

Indeed, the effects of colonial border-making were significant, but they did not systematically lead to the state’s collapse. Somalia’s post-independence trajectory was shaped by a blend of forces: Cold War militarization, authoritarianism, the politicization of clan networks, frequent droughts and economic shocks, and the abrupt withdrawal of external support sustaining its coercive capabilities. When the central authority faltered, it didn’t merely vanish; governance fragmented into various forms—local administrations, business-supported security arrangements, clan-based conflict resolution systems, and later, Islamic courts—each promising a degree of order in return for loyalty and taxes.

The early 1990s collapse also highlights the political economy behind humanitarian disasters. Famine was not just a natural occurrence but a complex market and security issue. Armed groups exerted control over key transportation routes, ports, and aid channels, converting food into both revenue and leverage. This reality rendered outside intervention inherently political: distributing aid meant determining who would benefit from the logistics of survival. External actors often regarded Somalia through a moral lens, either as a rescue operation or a cautionary example, rather than recognizing it as a battleground for control over resources and power.

Somalia further illustrates a recurring U.S. misstep: treating counterterrorism as a strategy rather than a supplementary tool. Disrupting violent networks without addressing the locally negotiated foundations of legitimacy risks creating a cycle of instability.

What U.S. Policy Should Have Been

A more effective U.S. approach to Somalia would have required reframing the situation along three interconnected dimensions, rather than oscillating between humanitarian intervention and counterterrorism.

- Treat Somalia as a political economy, not a rescue mission. The goal should have been to reshape incentives within a conflict economy—supporting authority in areas where security, dispute resolution, and commerce align, while countering it where exploitation prevails.

- Subordinate force to legitimacy rather than replacing it. While military power can disrupt violent actors, it cannot create sustainable authority. The prevalent error has been to view counterterrorism as the primary strategy rather than a supportive measure. Security assistance should have been conditioned on civilian protection and institutional efficacy, recognizing that legitimacy in Somalia is negotiated and locally grounded. When force dictates governance, stability becomes an elusive goal.

- Anchor intervention in regional and material realities. Somalia’s instability cannot be viewed as solely an internal issue. External influences, rivalries between neighboring countries, and economic flows across borders have continually shaped local conditions. Comprehensive policy should have treated regional diplomacy, aid logistics, and market operations as fundamental to stabilization efforts. Humanitarian delivery, in particular, needed strategies that mitigated capture and profiting from war, acknowledging the illusion of “neutral aid” in a fragmented security context.

The U.S. mistakes in Somalia exemplify a broader trend: a recurring failure to comprehend complex political economies, substituting episodic humanitarian efforts and narrow security frameworks for engaged, incentive-aware statecraft.

U.S. airstrikes in Somalia, 2025 — continuing a decades-long pattern of ineffective military intervention

The Cost of Simplistic Diagnosis

The significant risk of monocausal reasoning is not merely analytical inaccuracies but misguided policies. Oversimplified explanations create the illusion that complex conflicts can be easily resolved. They encourage major powers to intervene with strategies ill-suited to the actual problems.

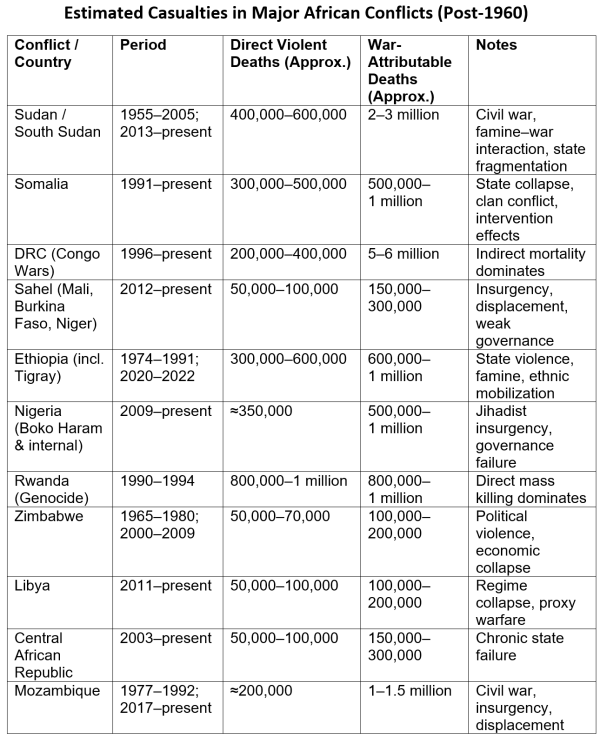

When Africa’s wars are simplistically framed as issues of terrorism, tribal conflict, or proxy disputes, the resulting crude interventions—arming selected factions, propping up fragile regimes, or freezing conflicts—oftentimes culminate in devastating human costs in terms of loss of life, destruction, and displacement. Concurrently, external actors incur sunk costs, face strategic distractions, and experience institutional decay. While these failures are not exclusively American, U.S. interventions are particularly notable for their scale and the misplaced confidence with which they apply inadequate approaches.

This intellectual shortcoming was evident when the Trump administration inaccurately described South Africa as a site of racial genocide. This was not merely a factual blunder, but rather the culmination of a prolonged decline in analytical depth, reducing complex political systems to slogans and grievance narratives.

South Africa’s challenges are real and significant, but they do not meet the criteria for genocide. The fact that such a misunderstanding could be articulated at the highest levels of U.S. government underscores a more profound failure: the erosion of any sustained ability to grasp African political realities on their own terms. The prevailing intellectual stance of U.S. foreign policy towards Africa has devolved into a cognitive equivalent of TL;DR—a refusal to engage with complexity that ensures misunderstanding.