Recently, the U.S. government has begun encouraging citizens to steer clear of “highly processed” foods, attributing many diet-related illnesses to them. This suggestion poses a challenge for many Americans since research indicates that while many desire to reduce their intake of ultra-processed foods, they often find it difficult to identify which foods fall within that classification.

“Advertising often misleads consumers into believing that certain foods are minimally processed when, in reality, they are ultra-processed,” states Alexandra DiFeliceantonio, a food selection neuroscience expert at Virginia Tech.

Highly processed foods are typically industrial products that include ingredients that are seldom found in a standard kitchen, such as preservatives, artificial sweeteners, color additives, and emulsifiers. Multiple studies have indicated that these foods are linked to a variety of health issues, including diabetes, heart disease, depression, and obesity.

“When inquiries arise about ultra-processed foods, people often struggle with aspects related to grains, carbohydrates, and starches,” says Dr. Dariush Mozaffarian, head of the Food is Medicine Institute at Tufts University. Such foods encompass items like breads, crackers, pretzels, pasta, and puffed grains. “People seek guidance on how to choose healthier alternatives,” he explains.

To assist his patients, Mozaffarian offers two straightforward rules to apply when selecting grains and starches: the 10 to 1 test and the water test.

1. The 10 to 1 test

“A food should have at least one gram of fiber for every 10 grams of carbohydrates,” advises Mozaffarian. For instance, if you’re examining a granola bar and the nutritional label indicates 30 grams of total carbohydrates, the item should also list at least three grams of fiber. If it falls short, opt for a different option.

This test, he notes, helps ensure that foods are not merely loaded with refined flours and sugars. “It’s crucial to maintain a balance of refined starches, whole grains, bran, seeds, and other nutritious ingredients,” he adds.

Additionally, the food should also satisfy “the water test.”

2. The water test

Take a starchy product — like a piece of bread, a cracker, or cereal — and place it in a glass of water. Allow it to soak for three to four hours and observe the outcome.

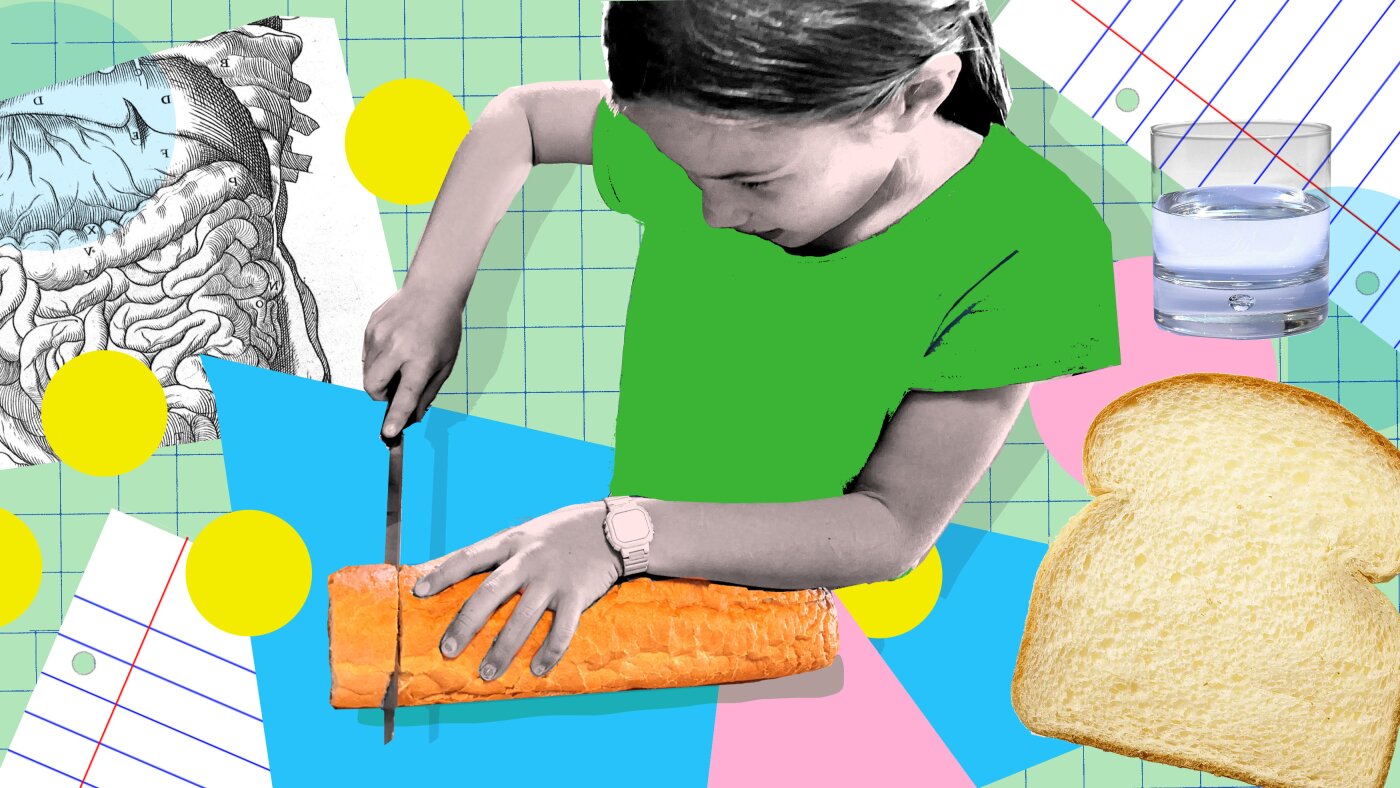

The author’s daughter tries out the water test for starchy food by soaking pieces of bread in a glass of water for a few hours.

Michaeleen Doucleff

hide caption

toggle caption

Michaeleen Doucleff

Pay attention to whether the grain or starch disintegrates or dissolves in the water, he explains.

Minimally processed grains, such as whole wheat bread and steel-cut oats, retain the plant’s cellulose structure, which encloses the carbohydrate chains, acting as a defense against dissolution in water.

If the carbohydrate doesn’t dissolve in water, it likely indicates a minimally processed food, which is a healthier option. This protective cell wall also slows digestion.

Following consumption, enzymes in your digestive system break down starches into simple sugars that subsequently enter your bloodstream. Mozaffarian likens the water test to the digestive process.

When the cell wall remains intact, digestive enzymes struggle to access the carbohydrates. Consequently, minimally processed grains are digested more slowly than their ultra-processed counterparts. Mozaffarian emphasizes that this method of digestion alleviates stress on the liver and metabolic hormones.

Slow digestion ensures that carbohydrates are processed deeper into the gastrointestinal system, providing sustenance for beneficial gut microbiota, or the microbiome, which is essential for overall health.

Conversely, ultra-processed grains and starches are constructed in a way that significantly alters their natural form, notes Dr. Meroë B. Morse, an assistant professor at MD Anderson Cancer Center. Factories effectively predigest these ingredients, stripping away the protective cell walls. “The grain or starch is ground to its individual components and then reassembled and bound together,” she explains.

As a result, enzymes digest these fast-acting carbs into simple sugars quickly.

“These foods are rapidly digested, often leading to glucose surges,” Morse elaborates. “When such spikes occur, insulin levels can rise.” Persistent spikes may contribute to insulin resistance and potentially diabetes, she cautions.

When selecting grains, starches, and other carbohydrates, it is essential to choose those that maintain their integrity in both your digestive system and in water.

This is where the water test proves beneficial.

The results of the water test using homemade bread (right) and a store-bought processed loaf (left).

Michaeleen Doucleff

hide caption

toggle caption

Michaeleen Doucleff

Specifically, observe whether the grain or starch disintegrates in the water, he adds.

Minimally processed grains like whole wheat bread and steel-cut oats have preserved their plant cell walls, which shield the carbohydrates from dissolving.

If the carbohydrates remain intact in the water, it’s a sign of a minimally processed food, which is favorable since the cell walls also contribute to slower digestion.

When carbohydrates are consumed, the digestive enzymes break them down into simple sugars that enter the bloodstream. This water test effectively models that digestive scenario.

When grains retain their structure, enzymes cannot effectively access the carbohydrates. This slower digestion compared to ultra-processed counterparts is beneficial, as it prevents undue stress on your liver and metabolic hormones.

This method of digestion also allows the carbohydrates to travel deeper into the digestive tract, feeding the gut microbiome, which is vital for overall well-being.

On the other hand, ultra-processed grains undergo a manufacturing process that diminishes their natural integrity, according to Dr. Meroë B. Morse from MD Anderson Cancer Center. Food companies essentially predigest these fibers and grains, stripping away their protective cell walls. “These ingredients are disassembled into their basic components and then reformed and glued together,” she explains.

This leads to rapid digestion of these carbohydrates into simple sugars.

“These foods are quickly digested, frequently leading to spikes in glucose,” Morse clarifies. “Whenever there are spikes, insulin levels typically surge.” Over time, such spikes may contribute to insulin resistance and, ultimately, diabetes, she warns.

Thus, as you make decisions about grains, starches, and carbs, choose those that retain their form, both in your gut and when subjected to the water test.

A Simple Experiment

Recently, my 10-year-old daughter and I experimented by baking a loaf of whole wheat bread at home. We decided to put it through the water test.

To compare, we also purchased a French baguette from the store, which contained preservatives, dextrose, wheat gluten, and other additives listed as “dough conditioner” and “crumb softener.”

We placed portions of both breads in separate glasses of water and waited for about three hours. After time passed, we examined each piece.

The homemade whole wheat bread soaked up some water but remained intact with no starch dissolving into the water. The water stayed clear. Ding, ding, ding! Our whole wheat bread passed the water test with flying colors.

Conversely, the French baguette displayed dramatic changes. “Wow!” my daughter exclaimed as she retrieved the bread from the glass. “It feels like a sponge, or slime, or Play-Doh!”

The baguette had absorbed a significant amount of water, practically transforming into a sponge that could be wrung out. Additionally, the water was cloudy due to the starch dissolving in it.

Bzzzzt! The baguette did not pass the water test, confirming that it is ultra-processed.

This test offered my daughter a visual and practical understanding of how ultra-processed breads may resemble homemade versions but behave quite differently in our bodies.

“That’s kinda gross,” she commented while squeezing the chunk of ultra-processed bread like a sponge. “Bread shouldn’t be like that.”

### Introduction

The recent shift in U.S. dietary guidelines encourages a reduction in highly processed foods, which have been linked to various diet-related diseases. This issue presents a challenge for many Americans seeking to improve their diet and health.

### Conclusion

With the simple water test and the 10 to 1 guideline, individuals can make informed choices about their carbohydrate intake