By Joe Fassler, a writer and journalist whose coverage of climate and technology has appeared in outlets such as The Guardian, The New York Times, and Wired. His novel, The Sky Was Ours, was published by Penguin Books. This article is cross-posted from DeSmog.

Since January, the beginning of the second Trump administration, at least 15 coal plants have postponed their planned retirements indefinitely, according to a DeSmog analysis. This shift largely stems from a projected increase in electricity demand, predominantly fueled by the expansion of high-powered data centers necessary for training and managing artificial intelligence (AI) operations. Moreover, some of these coal facilities have been ordered to remain operational by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), despite their considerable environmental and economic impacts. Energy Secretary Chris Wright, a former fracking executive, has often cited the need to “win the AI race” as a justification for renewed investments in coal.

These fossil fuel plants span various regions from Maryland to Michigan, and Georgia to Wyoming. In 2024, their coal-fired generators emitted over 68 million tons of carbon dioxide, surpassing the combined emissions of Delaware, Maryland, and Washington, D.C.

Shockingly, almost 75 percent of these coal plants were initially slated for closure within two years.

This delay contrasts sharply with the nationwide trend, where coal’s role as an energy source has declined rapidly over the last two decades. Critics assert that this phase-out is urgent for public and environmental health, with coal often referred to as the “dirtiest fossil fuel.” It generates more climate emissions per gigawatt-hour than any other energy source. A 2023 study in Science linked 460,000 additional deaths in the U.S. between 1999 and 2020 to sulfur dioxide particulate pollution from coal plants.

Cara Fogler, managing senior analyst for the Sierra Club, called the recent trend of delayed closures “unacceptable.”

“These coal plants are outdated, costly, and are polluting the air,” said Fogler, who co-authored a report revealing that many utilities have reversed their commitments to climate action, including coal phaseouts, frequently citing data centers as a factor. “These plants need to be planned for retirement, and it’s alarming to see utilities dodging these crucial steps.”

DeSmog identified the 15 affected plants by analyzing changes in their planned retirement dates as reported by the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) and public statements from utilities and the Trump administration. Some of these voluntary delays appear to contradict prior net-zero pledges made by multiple companies.

Neither the Department of Energy nor American Power, a trade association for the U.S. coal industry, responded to requests for comment.

Factors Behind Coal’s Decline

Not long ago, coal was vital for keeping the lights on, providing about half of America’s electricity in 2005. However, over the past two decades, coal’s market share has rapidly diminished, with no new coal plants coming online since 2013. Its share in the overall energy mix has dipped to merely 16 percent.

President Trump attributed coal’s struggles to environmental regulations, aiming to reverse this trend. “The miners told me about the attacks on their jobs and their livelihoods,” Trump expressed during a speech at the EPA. “I promised them… My administration is ending the war on coal.”

America is blessed with extraordinary energy abundance, including more than 250 years worth of beautiful clean coal. We have ended the war on coal, and will continue to work to promote American energy dominance!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) May 18, 2018

However, environmental regulations weren’t responsible for coal’s decline; instead, its downfall became inevitable with the rise of a rival fossil fuel: natural gas.

Natural gas possesses both economic and technological advantages over coal, according to economist David Lindequist of Miami University, who co-authored a study on the environmental effects of the shale gas surge.

As innovations in fracking technology flooded the U.S. market with cheap gas in the mid-2000s, utilities began a widespread switch from coal to gas that persists today. The availability of cheap, efficient gas transformed power generation, making it an attractive alternative for many energy providers.

“We would not have been able to phase out coal so effectively in the U.S. without the fracking boom,” Lindequist stated.

Today, coal faces an even steeper disadvantage as renewable energy sources capture market share. The International Renewable Energy Agency noted that, in 2024, solar and wind energy often produced electricity at a lower cost than fossil fuels, with solar emerging as the fastest-growing source of power in the U.S.

Moreover, the most recently constructed coal plant, Sandy Creek near Waco, Texas, built in 2013, remains idle due to ongoing issues and isn’t expected to resume operations until 2027. The average U.S. coal plant is now over 40 years old, contributing to their decreased reliability.

“These coal plants are so old that there’s little hope for revitalizing them,” remarked Michelle Solomon, manager in the electricity program at the nonpartisan think tank Energy Innovation. “They resemble an old car: no upgrades are going to make a car with 200,000 miles run like new.”

During the Biden administration, as technological innovation and significant subsidies made renewable energy more appealing, it was widely assumed coal’s time was limited. Lindequist noted, “The writing is on the wall for coal.”

“Coal may maintain a foothold in U.S. politics, but its actual generation capacity is diminishing each year,” stated researchers for the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis in a 2024 report. “This trend is irreversible.”

Nevertheless, prior to Biden’s exit from office, a new trend began: as tech corporations announced substantial data center projects to support the AI boom, utilities reassessed their coal operations.

The Impact of Data Centers on Coal

In 2020, Dominion Energy, which provides electricity to millions in Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina, announced non-binding plans to close the Clover Power Station by 2025, as operating the plant—a coal-fired facility—was deemed financially unfeasible.

Yet just three years later, Dominion predicted that energy demand from data centers could nearly quadruple by 2038. Virginia, known as Data Center Alley, houses over one-third of the world’s largest data centers and currently anticipates retaining its coal plants—including Clover—until at least 2045, coinciding with its state mandate for a carbon-free economy.

Dominion was not alone; other utilities cited data center demand in their decisions to backtrack on coal. During an earnings call in August 2024, executives from Alliant Energy, based in Wisconsin, stated they were “actively pursuing” data center projects. Shortly after, Alliant postponed the retirement of the Columbia Energy Center, a coal facility near Madison, extending its closure timeline from 2026 to 2029.

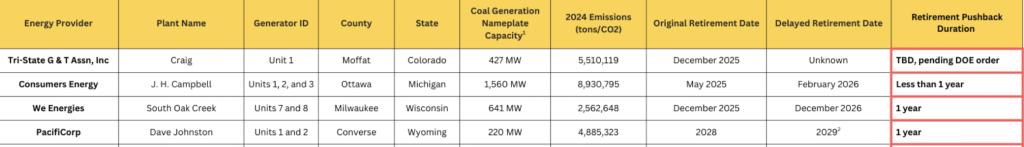

Utilities have postponed the retirements of at least 15 U.S. coal plants since President Trump took office in January 2025. Data source: U.S. Energy Information Administration. Credit: Joe Fassler/DeSmog

The trend garnered attention from analysts at the Frontier Group, an environmental think tank. In January 2025, analyst Quentin Good published a white paper showing that utilities cited data center growth as justification for delaying the phase-out of several fossil fuel plants across the U.S.

“We were alarmed at the possibility of this new demand from data centers hindering the transition to clean energy,” he told DeSmog. “In that report, we saw it was already happening.”

Meanwhile, two other dynamics emerged in January: the fervor surrounding AI intensified, and leadership in Washington changed.

Rising Demand Amid AI Developments

Data centers aren’t solely responsible for the recent surge in electricity demand. Factors like electrification of buildings, industrial growth, and the rise of electric vehicles also contribute. However, the rapid proliferation of data centers has drawn utilities’ attention due to their localized energy impacts, cropping up at an unprecedented rate. As these facilities, equipped with extensive computing apparatus, are expected to account for about half of the new electricity demand between 2025 and 2030.

The landscape shifted on January 21, 2025—just one day after President Trump’s inauguration—when he unveiled the Stargate Project, a joint venture involving ChatGPT’s parent company OpenAI, which aims to invest up to $500 billion in data center expansions over four years. Tech executives joined Trump to announce the project’s details at a White House gathering.

Shortly thereafter, Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg revealed intentions to invest $65 billion in data centers in 2025 alone, including plans for a project “so expansive it would cover a large portion of Manhattan.” These revelations followed similar commitments from Microsoft, pledging $80 billion for data centers this year.

As leading tech corporations vied to outdo each other, coal plant retirements began to dwindle.

On January 31, Southern Company, servicing over 9 million customers in 15 states, announced plans to defer the retirement of coal generators at two major plants in Georgia, pushing the timeline from between 2028 and 2035 to as late as January 1, 2039. In their public statements, representatives referenced data center projects as a major reason for the delays.

“We’re extending the lifespan of coal plants for as long as we can because we need them on the grid,” said Southern Company’s CEO Chris Womack at an industry conference.

In Mississippi, Southern Company also postponed the closure of a 500 MW generator at the Victor J. Daniel coal plant from 2028 into “the mid-2030s.” They attributed this decision to a 500 MW Compass Datacenters project.

Data centers have shifted the dynamics in U.S. energy markets, prompting analysts like Good to keep track of the numerous delays. By October, he found that data centers had forced the postponement of at least 12 coal plant closings in recent years.

“The boom in data centers shows no signs of slowing,” he concluded, stating they have extended the operational lifespan of numerous fossil fuel plants.

In its analysis, DeSmog identified at least 15 coal plant retirements delayed since the beginning of 2025, collectively contributing to nearly 1.5 percent of America’s total energy-related carbon dioxide emissions for 2024. This situation unfolds as countries globally aim to cut climate emissions by approximately half to mitigate severe impacts of climate change, according to a recent United Nations report.

However, not all delays can be attributed solely to data center growth; recent orders from the Trump administration also played a crucial role.

Government Intervention

The J.H. Campbell Generating Plant, a coal plant in Ottawa County, Michigan, was supposed to close on May 31, even planning public tours to showcase its aging infrastructure. Yet, just days before its scheduled shutdown, DOE Secretary Chris Wright ordered a 90-day extension, citing an energy emergency in the Midwest.

This decision cost Consumers Energy nearly $30 million in a span of five weeks. Though the plant’s closure was projected to save ratepayers over $650 million by 2050, keeping it operational reportedly costs over $615,000 a day. Wright’s order has now been renewed multiple times, extending Campbell’s life until at least February 2026.

Michigan Attorney General Dana Nessel is challenging the DOE’s order, calling it “arbitrary.”

“The DOE is fabricating an emergency based on outdated information, ignoring publicly available truths,” Nessel stated in a recent press release. “It needs to cease its unlawful tactics to keep this coal plant running, particularly when it has already led to substantial financial losses.”

Meanwhile, the DOE presents an alternative view. “Beautiful, clean coal will be indispensable for powering America’s reindustrialization and securing victory in the AI race,” Wright stated in September while announcing $350 million for coal plant upgrades and other support.

Energy Innovation’s Solomon termed the funding “a waste of taxpayer money.”

“We describe it as a ‘cash for clunkers’ program without the exchange of old vehicles,” she said. “Attempting to create a modern electricity grid based on the most expensive and least reliable power source is misguided.”

Yet the Trump administration intends to accommodate the AI surge—projected to demand an estimated 100 gigawatts of capacity within five years—by maintaining more antiquated coal plants. “Most of that coal capacity is expected to remain online,” Wright elaborated.

Executives from Colorado’s Tri-State Generation and Transmission Association also confirmed plans to keep a 421 MW coal generator at Craig Station operational beyond its scheduled December 2025 closure.

In late October, Colorado Congressman Jeff Hurd urged the Trump administration to prolong the operation of a 400 MW generator at the Comanche Power Station amid ongoing repairs needed for the plant’s main reactor. Although this unit was slated to close in December, the administration did not need to intervene; Xcel Energy successfully lobbied to extend its operation by at least 12 months.

This decision arose not purely due to data center demands, though such demands are growing in Colorado. Xcel spokesperson Michelle Aguayo commented that the delay was “a result of various factors,” including rising electricity demand, “supply chain difficulties,” and the ongoing outage at the main generator. “We continue to make substantial progress toward our emission reduction goals as mandated by the state, requiring us to phase out coal units by 2030,” she noted.

Postponing the Inevitable

It remains uncertain how the data center boom will unfold as anticipated.

A recent report from power consulting firm Grid Strategies indicated that utilities may be overestimating electricity needs from data centers by as much as 40 percent, attributing this to speculative projects and instances of double-counting, where tech companies propose multiple projects across various regions while seeking incentives, thus artificially inflating the demand forecast.

Experts have coined a term for this phenomenon: “phantom data centers.”

In tandem, a growing chorus of critics warns of a potential AI bubble, arguing that soaring costs may not justify the extensive investments being proposed. Even the leader of Google’s parent company has acknowledged the “irrationality” of the current boom.

Critics argue that contradictory actions taken by the Trump administration—proclaiming an “energy emergency” while simultaneously canceling billions in funding for renewable projects—only exacerbate the situation.

Despite the uncertainties, one fact remains clear: While coal’s operational duration in America may be temporarily extended, it cannot last indefinitely.

Seth Feaster, an analyst with IEEFA, asserts that even the AI development surge does not alter the bigger narrative: ultimately, coal will decline, overshadowed by cheaper energy alternatives.

He characterized the current situation as a mere “period of pause and delay.” In his perspective, the technological and economic imperatives to phase out coal are undeniable.

“Policy changes might temporarily postpone coal’s decline, but they will certainly not derail the trajectory of coal’s future,” he told DeSmog.

The pressing questions now revolve around the extent and duration of these delays—and the associated costs.