The Philippines has often been characterized as a nation beset by a series of internal conflicts, ranging from colonial rebellion and communist insurgency to separatist struggles and Islamist terrorism. This portrayal, however, overlooks a more profound and continuous issue. The reality is that the Philippines has endured a long-standing environment of disruptive warfare, largely influenced and maintained by its integration into U.S. grand strategy since 1898. Following this integration, internal conflict began to be viewed not merely as political failure but as a manageable security concern, as long as the nation’s strategic alignment was upheld. Consequently, this has led to over a century of instability, driven by the Philippines’ status as an American strategic asset.

Before the Pivot: Spanish Rule and Incomplete Integration

The Spanish colonization of the Philippines, which commenced in the sixteenth century, never culminated in a fully integrated administration. Governance was marked by unevenness, heavy extraction, and reliance on local middlemen rather than sustainable institutions. Significant parts of the archipelago, especially in Muslim-majority Mindanao, were never completely subdued or assimilated. Chronic resistance, fragmented authority, and weak political cohesion characterized this era.

This historical context is important not solely due to the brutality or incompetence of the Spanish rule, but because it left a disjointed political framework behind. While there were instances of rebellion, these were sporadic and localized rather than institutionalized as a permanent security concern. This situation would undergo a significant transformation at the close of the nineteenth century.

1898: From Colony to Chess Piece

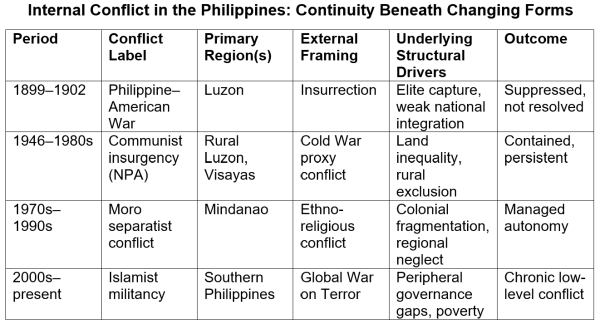

After the Spanish–American War in 1898, the Philippines transitioned into an American territory but, more critically, became an American strategic outpost. For Washington, the archipelago evolved from a struggling former colony into a vital position in the Pacific—a gateway to Asia and a testament to U.S. power.

This reevaluation of governance shifted the approach to internal conflict. The ensuing Philippine–American War was not merely about conquest; it represented one of the earliest examples of modern counterinsurgency. Methods such as pacification, intelligence collection, population control, and the professionalization of security forces became essential governance strategies. Internal violence was redefined: instead of being a political failure needing resolution, it became a technical issue requiring management.

By 1902, organized resistance to U.S. control had been effectively quelled. The tactics employed, including targeted intelligence operations combined with population management and punitive actions, illustrated that insurgencies could be defeated without rectifying their political roots. While destructive and costly, this approach restored a level of order deemed sufficient for strategic objectives. Importantly, it set a precedent for viewing counterinsurgency as an actionable problem rather than a political one, a lesson that would reverberate through U.S. military doctrine with dire consequences.

The Philippines thus assumed its role within the American security framework not as a sovereign project to be finalized but as a site to be maintained. This strategic transformation did not occur in isolation: at the dawn of the twentieth century, American military philosophy, heavily influenced by naval theorist Alfred Thayer Mahan, emphasized that national power hinged on maritime supremacy, forward bases, and control of essential sea routes. In this context, the Philippines was valued less for its internal cohesion and social progress than for its geographic positioning in the Western Pacific.

The archipelago was envisioned not as a nation to be unified but as a platform to hold. Internal stability was not deemed necessary; merely manageable disorder sufficed. From the start, the Philippines entered U.S. grand strategy as a positional asset, with its internal conflicts relegated beneath external necessities.

The Japanese Gambit

The Japanese occupation of the Philippines during World War II highlighted the strategic rationale that had already shaped American policy. Japan did not occupy the archipelago due to its internal dynamics but rather because of its crucial location along vital maritime routes and its utility as a forward base. The rapid downfall of U.S. defenses in 1941 exposed a harsh truth: in great-power rivalry, the Philippines’ internal stability was strategically inconsequential. Denial, access, and control became critical aspects. The war further cemented the view of the Philippines as a positional asset whose fate was subject to external strategic competition rather than as a sovereign nation to be preserved for its inherent value.

The lessons drawn by the United States from this conflict were not centered on enhancing Philippine political unity; instead, they emphasized the necessity of ensuring strategic alignment and access under all circumstances. When America returned post-war, it reaffirmed a security posture aimed at preventing strategic losses rather than achieving complete political integration.

Permanent Counterinsurgency as Normality

In the postwar period, counterinsurgency solidified into the norm for governance. Philippine security institutions focused more on containment than resolution. Stability became the suppression of threats to a manageable level rather than the eradication of the systemic issues that caused them.

This strategy proved resilient. Insurgencies could be weakened, fragmented, or temporarily subdued without ever being fully resolved. Security forces honed their tactical effectiveness, and external aid flowed consistently. The state endured, elections were conducted, and formal sovereignty was upheld.

However, what failed to materialize was a political resolution capable of integrating marginalized regions, addressing issues of land disparity, or dismantling the motivations behind rebellion. Low-intensity conflicts became a sustainable norm. In this sense, disorder was not a failure of governance but rather the equilibrium produced by the system.

Recurring Insurgency

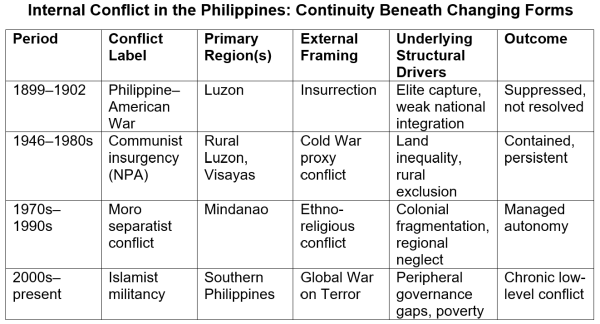

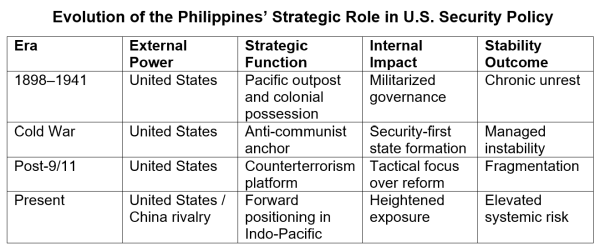

The ongoing internal conflicts in the Philippines have often been conflated with evolving ideological labels. Communist insurgency, Moro separatism, and Islamist militancy have each been treated as separate issues requiring unique solutions. In reality, these movements share a common background rooted in neglect, weak political integration, elite capture, and security-first governance strategies.

While the ideological outlooks shifted, the structural issues remained unchanged. Armed groups fragmented, reassembled, and rebranded. The New People’s Army has risen and fallen, while Moro factions divided, negotiated, and rearmed. The adoption of Islamist terminology offered a fresh narrative for a long-standing issue. Each new iteration of conflict secured renewed security assistance while postponing the critical political and economic reforms essential for lasting peace.

Persistent insurgency was not a deliberate agenda for the United States, but its repercussions aligned with American strategic interests. As long as internal conflict remained manageable, it fostered security cooperation, reinforced institutional reliance, and facilitated strategic alignment without necessitating substantive political transformation. Instability was not explicitly sought but tolerated, managed, and ultimately institutionalized.

Advising Without Resolving

Throughout this period, the U.S. role has remained consistent. Training missions, advisory deployments, intelligence sharing, and joint exercises have enhanced the tactical capability of Philippine forces. While these initiatives have shown success on a limited scale, they have failed strategically. Metrics often measured operational success rather than long-term impacts. Kill and capture statistics became substitutes for meaningful political integration. Professionalization of the military deepened dependency. Each new phase of assistance optimized the system for ongoing management rather than fundamental change. This pattern is prevalent across U.S. security partnerships, but what sets the Philippines apart is the duration: over a century of security engagement without any structural resolution.

The closure of major U.S. bases in the early 1990s seemed to signal a shift in strategy. The Philippines reclaimed its sovereignty, declined permanent basing, and sought greater autonomy from American military oversight. Yet the core security relationship remained intact. Internal conflicts continued, military capacity stayed limited, and reliance on external support persisted through various advisory missions and access agreements. As regional dynamics grew more competitive, the strategic rationale resumed with minimal friction. This episode illustrated that while the Philippines could distance itself from the visible presence of U.S. military forces, it could not escape the underlying functionality within American grand strategy.

This enduring relationship was formalized in 2014 through the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA), permitting U.S. forces rotational access to specific Philippine military facilities, allowing prepositioning of equipment, and authorizing temporary infrastructure development. While EDCA does not officially reinstate permanent U.S. bases, it effectively maintains rapid access and surge capabilities. In a crisis, this arrangement would enable a substantial U.S. military presence in the Philippines without the political delays associated with renegotiating basing agreements. Thus, the distinction between access and basing becomes largely administrative rather than strategic.

The Chess Game Resumes

As tensions between the United States and China heighten, the geographic significance of the Philippines has returned to the forefront, augmenting its strategic value yet again. The necessity for base access, proximity to maritime routes, and forward positioning has enhanced the archipelago’s relevance in the shifting landscape of Indo-Pacific security. U.S. security collaborations now increasingly focus on access, interoperability, and presence, positioning the Philippines closer to the epicenter of disputes concerning maritime boundaries and regional authority.

What remains unchanged, however, is the persistent internal fragility of the nation. Peripheral areas continue to lag in development. Infrastructure vulnerabilities are prevalent. Defense capacities are limited. The very conditions that previously made managed instability acceptable—the ability to contain conflict, a foundation of external security support, and deferred reform—now expose the nation to heightened risk in a climate of great-power rivalry. A state with constrained defense autonomy and ongoing internal insecurity has limited options for strategic nonalignment. In such circumstances, alignment with a potential aggressor often reflects a necessity rather than a choice. A nation valued primarily for its geographic position becomes increasingly vulnerable as competition between major powers escalates.

The Sacrificial Piece

The peril of being regarded purely as a strategic pawn lies not just in the manipulation involved but in the potential for outright sacrifice. In the event of a significant regional conflict, the devastation of the Philippines could occur without the need for direct invasion or occupation. Precision strikes, disruptions of infrastructure, and economic harm could suffice to render the Philippines strategically unusable for both parties. Such an outcome would not be a mere unfortunate error; rather, it would be a conceivable result of a century-old trend wherein the Philippines’ primary value rests in its strategic position rather than its stability. Managed instability can be deemed acceptable until circumstances evolve toward war, at which point management becomes irrelevant.

The plight of the Philippines is not purely about its history of conflict; rather, it pertains to its recurrent role as a battleground where upheaval is tolerated to serve the interests of larger powers. When a nation is perpetually treated as a pawn for long enough, its well-being becomes secondary, and its potential sacrifice morphs into an option within strategic calculations.