Introduction

In my previous discussion about U.S. manufacturing jobs and tariffs, I referenced an article from the Wall Street Journal that highlighted how American tariffs have had minimal effect on Chinese exports, as these exports are merely redirected to other countries. In this article, I will explore the implications of this shift for the distribution of the tax burden associated with tariffs.

Economists generally contend that the primary burden of a tariff falls on the importing nation. Our introductory economic models typically illustrate that the entire burden of a tariff rests with the importing country. However, readers of this blog are aware that it’s not entirely accurate to claim that a tariff consistently impacts only the importing country. In our introductory courses, we also teach that the distribution of this burden depends on the relative elasticities of supply and demand. Essentially, those who are less responsive to price changes will bear a larger share of the tax burden. Conversely, those who are more sensitive to price fluctuations will carry a lighter load. In classical economic models of international trade, we often assume that the supply of imported goods is perfectly elastic, meaning that foreign producers are highly responsive to price shifts; they can easily redirect their goods to other markets. As a result, the importing nation bears the full burden of the tariff, a scenario described by the small-country tariff model, which assumes the importing nation cannot influence the global price of the goods subject to tariffs.

But what happens if this condition is not met? What if the importing country is large enough to sway the global price of the good? This situation is referred to as the large-country model. When a nation is a significant importer of a specific product, its actions can affect the world market price. As this large importing nation increases its purchases, the global supply expands, raising world prices. Conversely, when it buys less, world prices fall, and global production decreases.

The large-country model presents an intriguing possibility: a modest tariff can actually improve a large country’s terms of trade. This means that the trading partner’s terms of trade may decline as a result. The terms of trade can be defined as:

Terms of Trade = Export Price Index / Import Price Index

To put it simply, the terms of trade measure the cost (in exports) for a country to consume (in imports) foreign goods. Imposing a tariff reduces the demand for the imported good. In the context of the large-country model, if the demand decreases significantly, the world price will also drop, forcing exporters to absorb part of the tariff burden; otherwise, their transactions would become unprofitable. While domestic imports decline, the domestic price of the good won’t necessarily rise by the full amount of the tariff.

In summary, if a country is considerably large, the elasticities of demand and supply are known, and the behavior of exporting nations remains unchanged (no retaliatory measures or reductions in their imports or investments), a modest tariff can enhance the importing country’s economic welfare. While there is some loss due to decreased imports (as imports are a significant benefit of international trade), the gain from reduced prices can lead to an overall increase in welfare, provided that the gain from lower prices surpasses the loss from diminished imports. This delicate balance underscores the necessity for the tariff to be small, as excessively high tariffs could harm the importation process. The optimal tariff, therefore, is the one that maximizes overall economic welfare within a country.

These concepts are covered extensively in any International Trade textbook. I recommend International Economics by Robert Carbaugh, which assumes the reader has only a foundational understanding of economics.

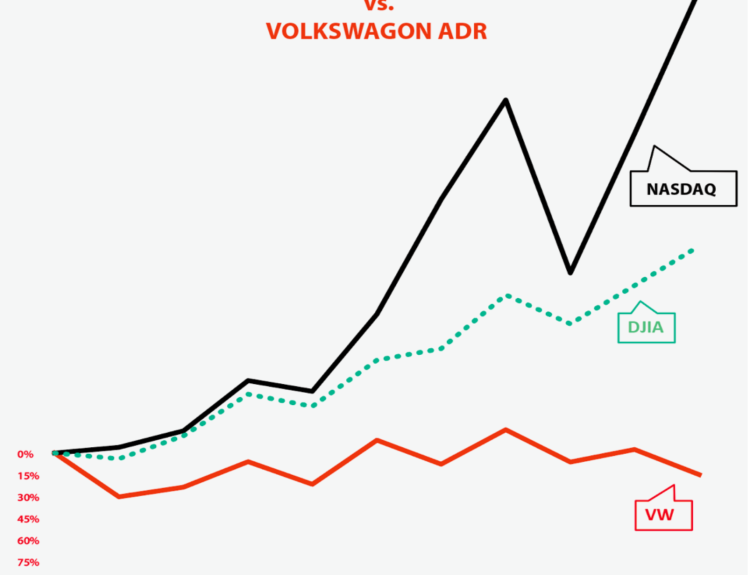

Some commentators argue that the U.S. is sufficiently large for the imposed tariffs to increase its welfare. However, evidence soon showed that the conditions for an optimal tariff were not met; shortly after the tariffs were enacted in 2025, other countries retaliated with their own tariffs. Various studies suggest that Americans are bearing nearly the entire burden of the tariffs.

A recent article in the WSJ brings to light another key point: regarding China, the U.S. is not large enough to wield influence. According to data from the U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. imports from China have decreased by approximately 45.6% from the previous year, yet China’s exports have increased. Instead of reducing prices, China has simply found alternative buyers for its goods. This indicates that U.S. consumers are likely shouldering most, if not all, of the tariff burden on Chinese products. As a result, the tariffs have led to decreased imports and increased prices for Americans without causing a shift in global prices; China found other markets instead.

The true value of a model lies in its ability to provide insights into real-world dynamics and offer predictive power. The complexity or “realism” of a model isn’t always an asset. In numerous ways, the large-country model is more reflective of reality than the small-country model. It’s improbable for any nation, including the United States, to be so small that it cannot exert at least some influence on world prices. However, the large-country model often falls short in explaining real-world results. The small-country model, though less realistic, tends to offer clearer analyses, especially as an initial approximation of the effects of tariffs and trade policies.

Conclusion

In conclusion, understanding the complexities and implications of tariffs requires careful consideration of how economic models apply to real-world scenarios. By recognizing how different models function, especially in terms of import behavior and price sensitivity, we can better analyze the effects of trade policies on both domestic and global economies.