Over the years, federal nutrition guidelines have undergone significant changes. Transitioning from the food pyramid to MyPlate, and now to an inverted pyramid model, these updates reflect shifting priorities and messaging. Every five years, new guidelines are issued, often resulting in changes that capture public interest.

On January 7, the USDA and HHS unveiled the 2025-2030 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA).

This latest update has garnered more attention than usual, provoking curiosity about what changes have occurred and their significance. To address these questions, I consulted with Megan Maisano, a registered dietitian nutritionist and nutrition contributor for YLE, who helped clarify the implications of these updates.

The DGA serves as the country’s primary nutrition policy framework, influencing federal food and nutrition directives to foster health and prevent disease through:

-

Establishing federal nutrition standards (e.g., for school meals and military dining facilities)

-

Guiding nutrition education initiatives (e.g., curriculum development)

-

Providing clinical practice tools and dietary assessment resources to clinicians for improved patient care

While some programs are mandated to adhere to the DGA, others utilize it as a reference for best practices. As a registered dietitian, I frequently rely on it as a credible, contemporary source of information.

Traditionally, the DGA has followed a two-step, five-year process:

-

An independent committee assesses the science and releases a Scientific Report.

-

The USDA and HHS create the final guidelines based on that report.

This framework is intended to enhance scientific rigor, transparency, and public confidence. Below is the planned timeline for the 2025-2030 DGA.

However, this year’s process deviated from the usual approach.

Three significant changes occurred:

1. Alteration in the scientific process. This time, instead of relying on the expert Scientific Report, the final DGA was shaped by a separate Scientific Foundation compiled rapidly and privately by contracted experts. This shift has sparked concerns about the integrity of the scientific process, transparency, and whether priorities influenced this federal advice.

The methodology matters, as it dictates which evidence is included, how it is analyzed, and whose expertise is taken into account. A hurried process with limited visibility raises apprehensions regarding trust, consistency, and the fortitude of upcoming guidelines as priorities shift over time.

2. The removal of health equity considerations. The new Scientific Foundation criticized the former report for its emphasis on health equity, opting instead to exclude it from the equation.

Health equity is crucial since factors such as income, cultural background, food accessibility, and representation in research profoundly impact dietary habits and health outcomes. Disregarding these aspects raises concerns about the guidelines’ applicability across various communities and real-world situations.

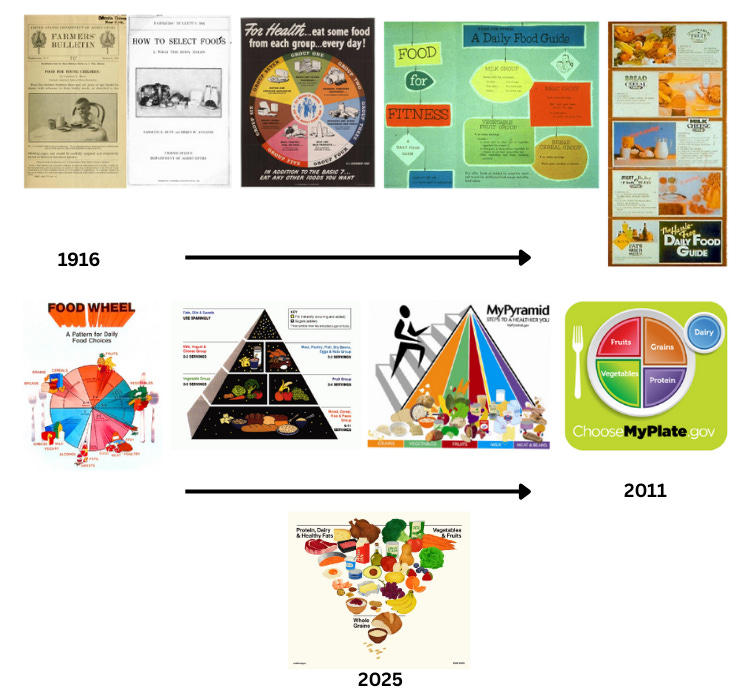

3. A more political tone. Messaging has adopted a more persuasive slant, at times bordering on propagandistic. During the DGA press conference, previous guidelines were described as “faulty” and “dogma,” leading to insinuations that “the government has been misleading us.”

This narrative blends scientific discourse with political rhetoric, potentially undermining public trust in health institutions and complicating health professionals’ ability to reference and implement these recommendations.

While the changes might seem minor, they can significantly impact the way nutritional guidelines are perceived.

The DGA continues to prioritize a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, protein, and dairy, while advising limits on added sugars, saturated fats, sodium, and alcohol. Nonetheless, there are some key changes worth noting:

1. “Real Food” as a focal point. There’s a heightened emphasis on consuming “real” foods while minimizing highly processed options. Although reducing ultra-processed food is beneficial, the term “highly processed” remains undefined. This messaging has even extended to cultural platforms, such as a Super Bowl ad that proclaimed: “Processed Food Kills.”

Why is this significant? With 48 million Americans facing food insecurity, including 1 in 5 children, stressing “real food” could stigmatize those who depend on processed foods for accessibility or convenience.

Furthermore, not all processed foods are detrimental; many can contribute positively to a healthy diet. Processing can enhance food safety, longevity, and nutrient absorption in cost-effective manners. Oversimplifying this complex issue could alienate communities that federal programs intend to assist.

2. Increased focus on protein. There is a higher emphasis on protein in the guidelines, highlighting animal-based sources. While protein is vital for satiety and health, balancing it with plant-based alternatives in dietary recommendations could promote more varied eating habits. Notably, it is rare for the DGA to revise daily protein recommendations.

Why is this important? Most Americans already meet their protein requirements, whereas only around 6% manage to meet fiber recommendations, a nutrient strongly linked to various health benefits. This shift prompts questions about the focus of these guidelines.

3. A revised approach to saturated fats. Food sources high in saturated fats, such as red meat, butter, and full-fat dairy, are now characterized alongside sources of “healthy fats,” including nuts and oils.

Why does this matter? There’s evidence indicating that the health implications of saturated fats differ based on the food source and preparation method. However, general endorsements may lack nuance. Although the suggested limit for saturated fat remains under 10% of daily caloric intake—an amount manyalready exceed—this shift could confuse the public, especially as heart disease continues to be a leading health concern.

4. Stringent added sugar limits. The latest guidelines advise complete avoidance of added sugars until age 10, limiting intake to less than 10 grams per meal afterwards, deviating from the earlier guidance of less than 10% of total calories after age two.

Why is this crucial? Setting firm guidelines is essential, particularly for children’s diets, which influence their lifelong eating habits. However, providing greater contextual flexibility regarding the different sources of added sugars and acknowledging healthier options with small amounts would benefit families navigating food choices.

Completely steering clear of added sugars until age 10 is often unrealistic for many households and could foster a negative relationship with food.

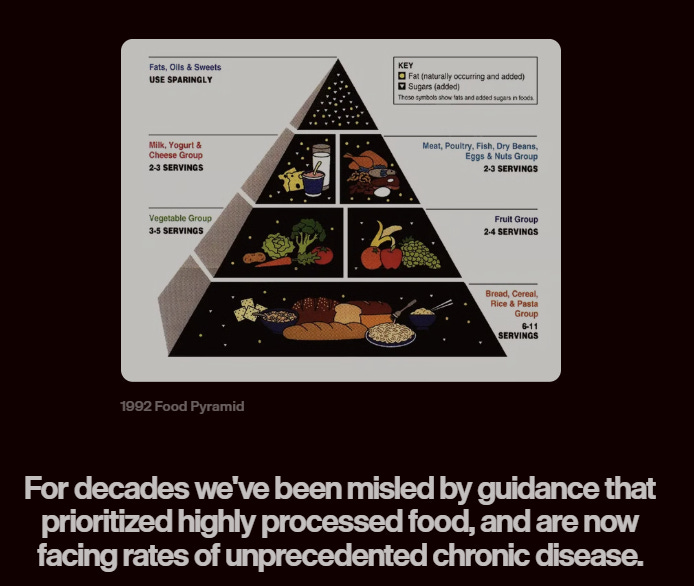

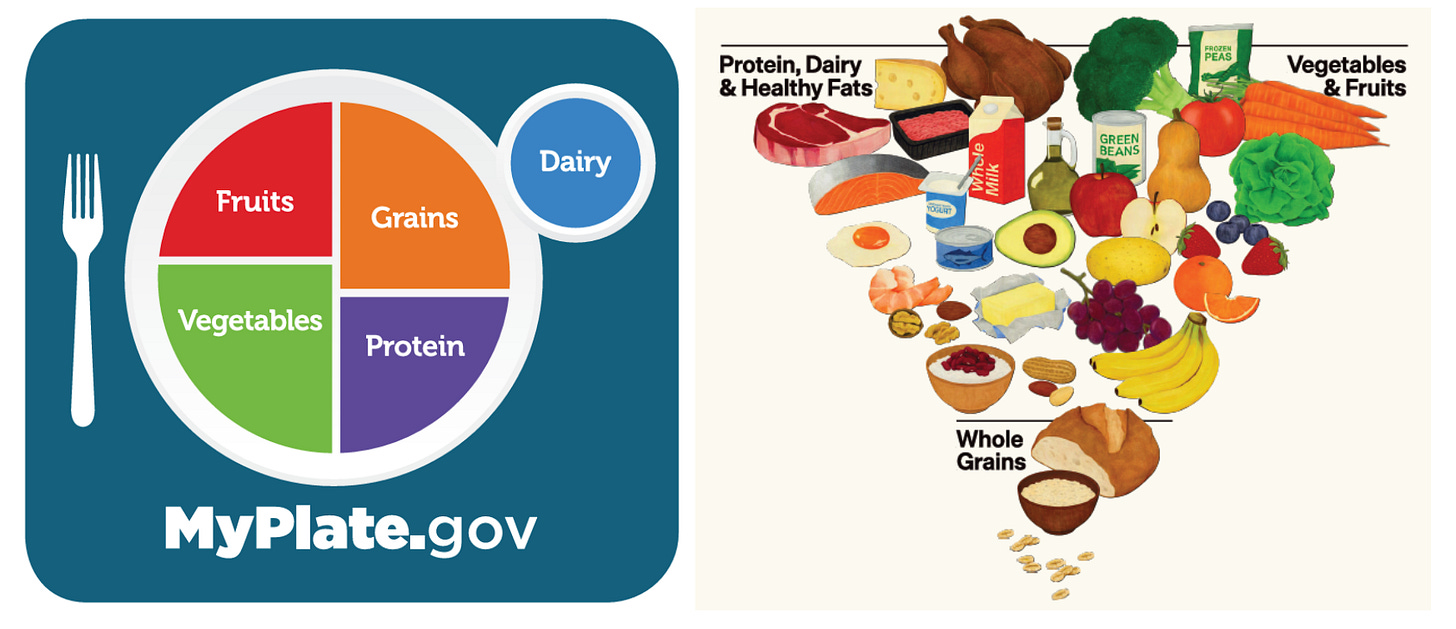

5. Introduction of a new graphic. The DGA replaces MyPlate with an inverted food pyramid. Protein, dairy, fats, vegetables, and fruits appear at the top, while whole grains are given less emphasis.

Why is this important? Though the new hierarchy is straightforward, the graphic lacks guidance on portion sizes or balance—elements that made MyPlate practical for daily use.

Most people may notice only slight differences, but institutions reliant on federal support will experience more significant impacts.

Why does this matter? Federal programs, such as school meal programs, WIC, and military dining must follow DGA recommendations. Strengthening messaging around “real food” and enforcing stricter sugar limits will necessitate additional funding, training, and kitchen resources, further straining already limited resources.

For individuals, the foundational aspects of health remain relatively unchanged: maintaining a nutrient-rich diet, engaging in physical activity, and minimizing substance use.

The 2025-2030 Dietary Guidelines retain numerous established recommendations while introducing notable changes, particularly in their development process and communication strategies.

Shifting away from transparent, scientific reviews toward a values-driven narrative raises concerns regarding trust and credibility. As the DGA influences nutrition policy, education, and public perceptions of healthy eating, these considerations are crucial.

In the realm of public health nutrition, the methodology behind the guidelines can be as significant as their content.

Best Regards, Megan

PS. Many of you raised specific queries, so instead of extending this post, I’ll address them in the comments. Join the conversation—I’ll be there!

P.S.S I continually seek to learn and frequently draw from the insights of other experts to refine and challenge my understanding. For more in-depth perspectives on the new DGA, consider exploring the insights of Kevin Klatt, Jessica Knurick, and Dariush Mozaffarian.

Megan Maisano, MS, RDN, is a registered dietitian nutritionist. Currently, she works with the National Dairy Council, a non-profit organization focused on dairy nutrition research and education (her writing for YLE does not cover the dairy industry). Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE) is created and run by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, wife, and mother of two young girls. YLE reaches over 425,000 readers across 132 countries, with the aim of translating the ever-evolving public health science to help people make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free to everyone, thanks to the generous support of YLE community members. To help sustain this effort, consider subscribing or upgrading below: