For over a decade, Americans have been consistently told that the United States possesses the most formidable military in history. This assertion is so frequently repeated that it has become accepted as a universal truth. It is used to reassure allies, deter opponents, justify global obligations, and quell domestic uncertainties. However, beneath this triumphant narrative lurks a more troubling reality: the U.S. military has been gradually decreasing in size, diminishing in readiness, expanding its leadership ranks, and becoming increasingly unaffordable in terms of mass and endurance. What remains is a force not optimized for prolonged combat against a peer competitor, but rather one focused on demonstration, reassurance, and bureaucratic maintenance. While much attention has been given to individual shortcomings—such as procurement issues, recruitment challenges, and readiness crises—the cumulative problems within the U.S. defense establishment reveal a deep-rooted erosion of capability disguised by inflated narratives.

Shrinking force behind expanding claims

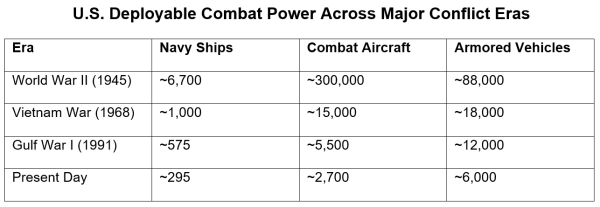

The long-term decline in U.S. military strength is stark. During World War II, the United States operated thousands of naval vessels, hundreds of thousands of combat aircraft, and tens of thousands of armored vehicles. Today, the Navy possesses fewer ships than it did before World War I, and both combat aircraft and armored forces have decreased significantly compared to Cold War figures.

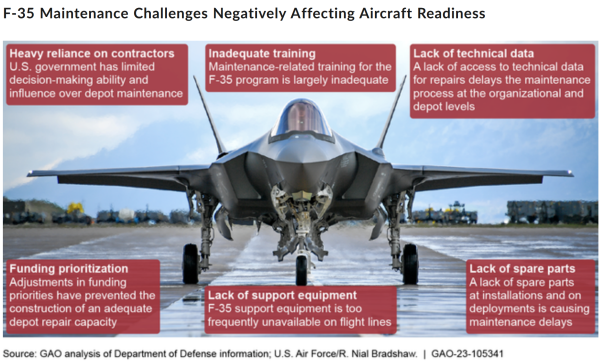

Commonly, one might argue that modern equipment is so advanced that fewer units are needed. However, this perspective falters in wartime situations. Precision does not negate attrition, sophisticated software cannot replace logistical needs, and high-tech systems can fail just as readily as their simpler counterparts—often requiring much longer repair times.

WWII B-24 bomber production – over 18,000 were built

Readiness: The Harsh Reality

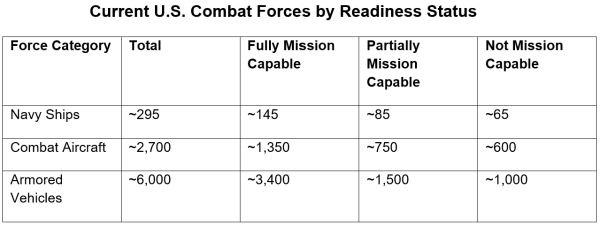

While the total inventory of military assets is concerning, the state of readiness is even more troubling. Across naval, air, and ground forces, only about half of the available units are fully mission-capable at any time. The remainder are either partially capable or non-deployable due to maintenance backlogs, parts shortages, or delayed repairs. Consequently, the effective operational strength of the U.S. military is significantly less than its reported total capacity.

Current readiness is increasingly sustained through resource canibalization, overworking crews, and intensive maintenance efforts—borrowing from future capabilities to meet present demands. This approach reflects fragility rather than resilience under pressure.

Leadership Inflation and Accountability Decay

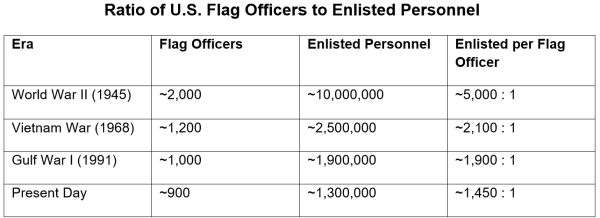

As both force size and readiness have deteriorated, the rank of senior leaders has expanded. The ratio of flag officers (generals and admirals) to enlisted personnel has more than tripled since World War II. This growth indicates increased bureaucratization and an aversion to risk rather than genuine operational need.

Failures in major weapons programs rarely lead to career repercussions. Strategic errors often become absorbed into procedural rhetoric, undermining the principle that leadership should entail accountability. During World War II, commanders were often removed or sidelined when their performance did not meet strategic requirements; today, generals involved in significant military failures often advance, signaling a system that rewards conformity and survival over effective results.

Cost Explosion and Shrinking Mass

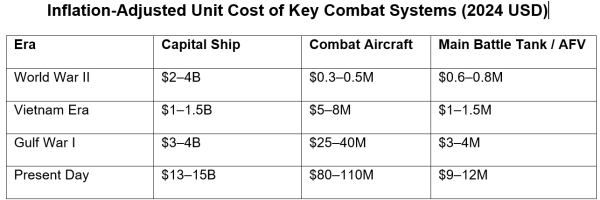

Modern U.S. combat systems have become prohibitively expensive. Inflation-adjusted unit costs for ships, aircraft, and armored vehicles have soared across different periods. As unit costs rise, the size of the force must decrease, making attrition strategically unacceptable. A military unable to afford the loss of its own equipment cannot effectively threaten or engage in war.

F-22 stealth fighter – 750 planned but only 187 built

B-2 stealth bomber – 132 planned but only 21 built

Nuclear Forces and the Limits of Substitution

Some argue that nuclear forces make conventional military structures less pertinent. This idea misinterprets deterrence, as nuclear weapons prevent total war by making any conventional miscalculation exceedingly perilous. They do not offset weakened conventional forces; instead, they heighten the stakes when those forces are overstretched or inaccurately represented. A hollow conventional military, reliant on nuclear arms, is not safer; it is more precarious, narrowing options for decision-makers while escalating the costs of errors.

Advanced Conventional Weapons and the Illusion of Technological Escape

Appeals to advanced conventional technologies—such as hypersonic weapons, unmanned systems, and artificial intelligence—do not rescue the current narrative. In many areas, the U.S. lacks a decisive technological edge and, in some instances, has fallen behind competitors in operational capability. While other nations have moved from experimental to routine deployment of advanced systems, U.S. efforts remain fragmented and delayed. Technological sophistication has become more of a compensatory narrative—one that further inflates costs, decreases production capacity, and increases reluctance to experience losses. The outcome is not dominance, but a contraction of real capabilities disguised by claims of future superiority.

What Now?

This diagnosis naturally evokes the question of what action to take. However, this inquiry presumes that the issue stems from policy changes rather than structural limitations. In truth, there are three possible paths forward, none of which are appealing.

1. Rebuild at Scale.

Theoretically, the United States could attempt to rebuild its military with a focus on mass and resilience: this would involve lowering technological aspirations, canceling high-profile projects, investing in industrial capabilities, and prioritizing quantity along with quality. Yet, in practice, this would necessitate decades of sustained political commitment, re-establishing industrial capacity, overhauling defense procurement processes, and dismantling entrenched institutional incentives—an endeavor currently lacking political support.

2. Shrink Commitments to Match Capacity.

A second option is to realign global commitments to match actual military capacity: reducing forward deployments, explicitly prioritizing specific theaters, and relinquishing the notion of universal deterrence. While this approach is strategically sound, it is politically fraught, as it appears as a decline, upsets allies reliant on U.S. guarantees, and contradicts the identity narratives held by elites. However, it remains the only choice that genuinely aligns objectives with available means.

3. Continue as We Are.

The third route requires no decisive action and is therefore the most likely: it entails increasing rhetorical inflation, diminishing operational margins, rising escalation risks, and a growing dependence on bluffing. This path does not lead to an immediate collapse, but rather a steadily increasing chance of catastrophic miscalculations.

The Need for Military Pragmatism and Accountability

The issues outlined here are not isolated incidents caused by a single flawed program, administration, or strategic decision. They are the cumulative result of decades of incentives favoring technological ambition over manufacturability, narrative comfort over factual accountability, and career longevity over responsibility. The outcome is a military set up to deter on paper, project power symbolically, and reassure rhetorically, all while quietly losing the capability to effectively conduct defensive and offensive operations. The realistic task before us is not to restore dominance, but to govern risk amidst overextension and illusion. This requires accurate assessments of capabilities, realistic prioritization over universal commitments, a humble acknowledgment of escalation dynamics, genuine accountability within military institutions, and restraint in narrative that tempers triumphalist assurances.

Conclusion

The peril of declining military capability extends beyond the fear of the United States potentially losing a future conflict. It lies in the growing misconception among decision-makers, allies, and adversaries that reserves of power and resilience still exist where they have dissipated. In this atmosphere, escalation becomes easier, restraint seems unwarranted, and risk is systematically mispriced. Nuclear weapons and sophisticated technologies do not mitigate this peril; instead, they exacerbate it by heightening the consequences of miscalculations while reducing recovery options. History has shown little mercy to great powers that trade substantive readiness for boastful narratives. A military system unable to confront its own truths invites the risk of misuse and operational failures. A nation that confuses posturing with real power flirts with disaster.