The current state of the stock market has left many investors feeling uneasy. While we’re witnessing significant interest in AI-related stocks, there’s a sense that we’re in a bubble that might inflate even further before experiencing a sharp correction. Historically, stock market declines, unless spurred by excessive debt—as seen during the Great Depression—don’t typically trigger a crisis, but they do impact the economy by forcing consumers and businesses to cut back on spending and investment. This reduction in demand can lead to recessionary conditions, contributing to deflation and economic stagnation. Thus, even a post-bubble hangover can inflict substantial harm.

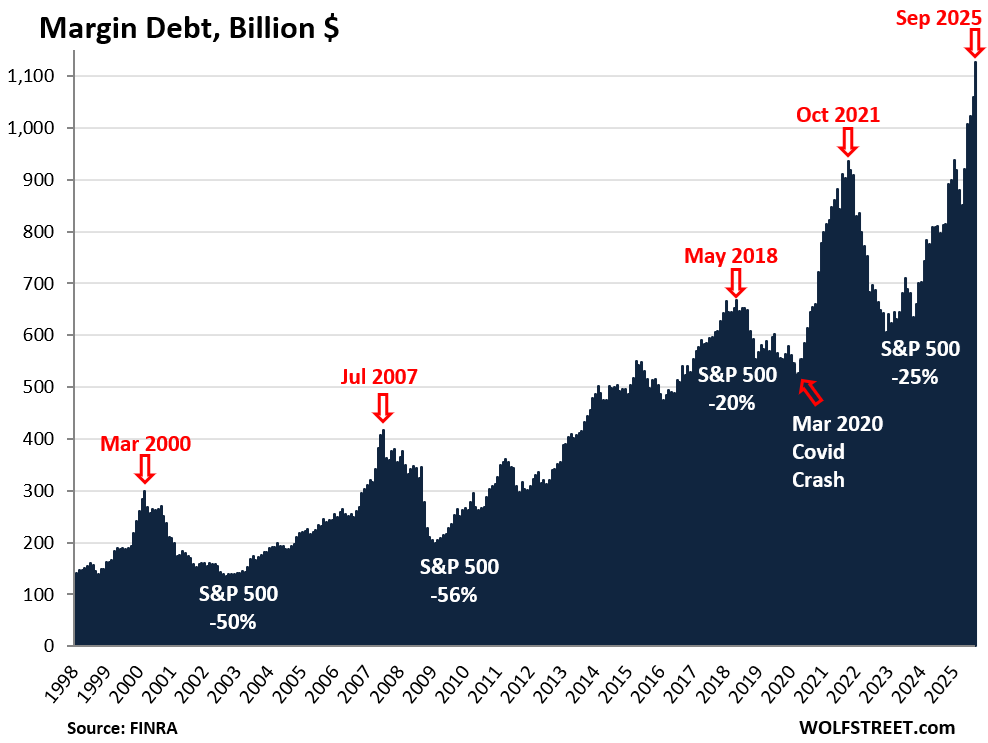

Several market analysis platforms, including one by Wolf Richter, have raised concerns about U.S. margin debt reaching an unprecedented high. Here’s Wolf’s chart along with a portion of his commentary:

Since April, leverage in the stock market has surged. In September alone, margin debt—representing the funds investors have borrowed from their brokers—increased by 6.3%, totaling a record $1.13 trillion…

This influx of borrowed capital into the stock market drives prices higher, acting as both an amplifier during upward trends and a magnifier during downturns. Prolonged increases in margin debt, reaching new heights, often lead to sharp sell-offs:

The overall picture painted by the chart is largely accurate, but it doesn’t tell us everything we need to know about the current state of stock market frothiness. Margin borrowing is tightly regulated, and when stock prices soar, margin borrowing tends to increase correspondingly. While the chart illustrates the rapid rise in stock prices, we must remember that when this exuberance fades, the resulting forced selling can exacerbate declines.

In a contrary viewpoint, Morningstar’s Brian Jacobs argued in August that margin debt is not necessarily a cause for alarm:

For Jacobs, the record margin debt that has accompanied the stock market rally isn’t as ominous as some believe. He regards it as merely a coincidental indicator reflecting market momentum rather than a sign of impending collapse.

Jacobs noted in a recent investment blog, “When equities rise, account values increase, prompting investors to take on more leverage. A 25% rise in margin debt over the past year aligns closely with the same increase in the S&P 500.”

However, while a basic examination of margin debt may simply highlight that stock prices have surged, a more nuanced analysis reveals concerning trends. At the end of September, Cory McPherson from Pro-Active Capital shared his findings in Margin Debt Showing Investors Going All In:

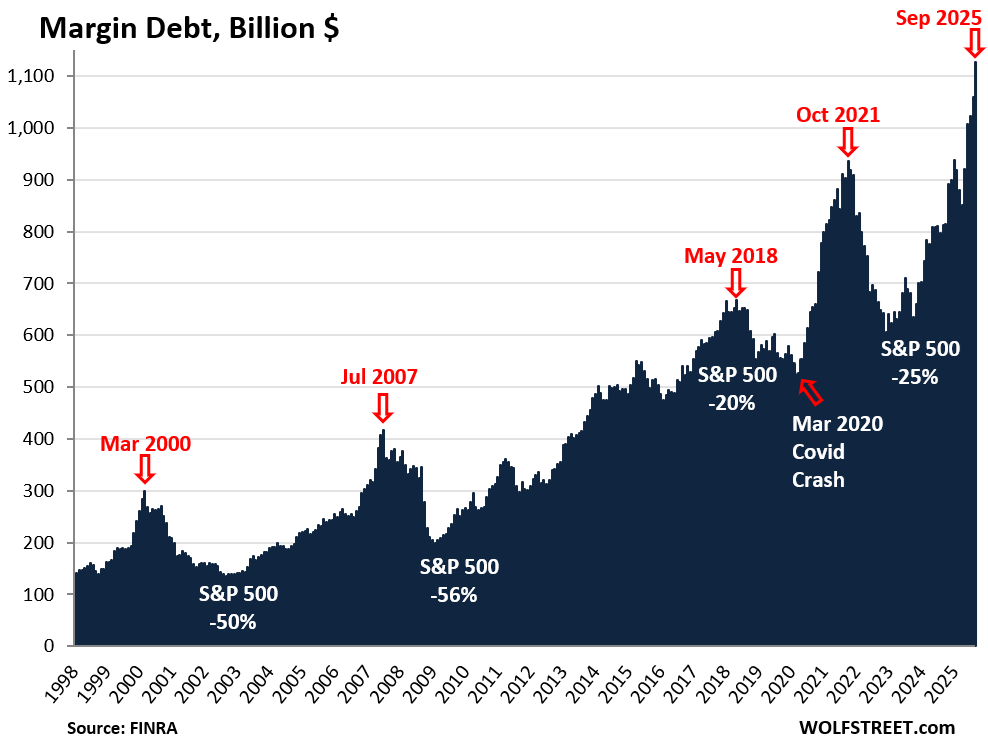

As of August 2025, margin debt, when compared to nominal GDP, stands at 3.48%. The all-time high occurred in October 2021 at 3.97%. Historically, this ratio peaked at 2.6% during the dot-com bubble in 2000 and 2.5% in 2007 before the Great Recession.

Another perspective is through the Margin Debt Carry Load, which considers the interest paid on margin debt. This metric shows that we have reached levels last seen in the final stages of the dot-com bubble. Importantly, margin debt alone doesn’t signal timing; it can continue to rise alongside the market. Yet this situation can lead to significant downturns, as forced selling occurs when stocks drop, creating a domino effect similar to the April plunge we observed.

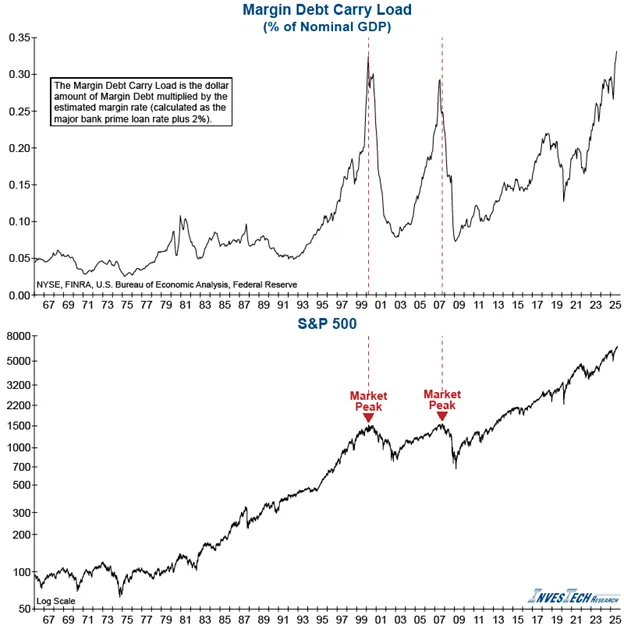

Another key indicator of market health, the price-to-sales ratio, has also reached concerning levels. This ratio, which measures what investors are willing to pay for each dollar of a company’s sales, shows that the S&P 500 has surpassed not only last year’s and 2021’s peaks but also exceeded values recorded during the dot-com bubble. Much of this top-heavy valuation is attributed to the tech sector and the ongoing AI boom, suggesting stock prices have outpaced actual sales performance. While such overvaluation doesn’t directly cause market corrections, it often precedes them.

McPherson also notes some economic anomalies: significant downward revisions in job numbers occurred without any accompanying recession, and the Conference Board’s leading indicators have been declining for three years while coincident indicators continue to rise. This suggests that persistent large-scale fiscal deficits can lead to perplexing outcomes.

The stakes are substantial because a great deal depends on the health of the stock market. The share of U.S. households’ financial assets held in equities has reached an all-time high:

⚠️This is truly INSANE:

U.S. households now own a RECORD 52% of their financial assets in equities.

This share has more than DOUBLED since the Great Financial Crisis and surpassed the 2000 Dot-Com Bubble by ~5 points.

They hold just 15% in cash and 14% in debt assets. pic.twitter.com/6DRmtxYSze

— Global Markets Investor (@GlobalMktObserv) October 13, 2025

Foreign investors have also significantly invested in U.S. markets. The Economist recently highlighted insights from Gita Gopinath, former chief economist of the IMF, stating:

American households have significantly boosted their stock market investments over the past decade and a half, drawn by strong returns and the prominence of U.S. tech firms. This has attracted foreign investors, especially from Europe, who have also benefitted from the strong dollar. However, this interconnectedness means any sudden downturn in American markets could have global repercussions.

To illustrate, a market correction comparable to the dot-com crash could erase over $20 trillion of wealth for American households—around 70% of U.S. GDP in 2024. This impact would be several times greater than the losses from the early 2000s crash. With consumption growth already slowing compared to the period before the dot-com crash, such a shock could reduce it by 3.5 percentage points, leading to a two-percentage-point decline in overall GDP growth well before accounting for drops in investment.

The global consequences would be similarly daunting. Foreign investors might experience wealth losses exceeding $15 trillion, about 20% of the rest of the world’s GDP. In contrast, past crises like the dot-com crash incurred foreign losses closer to $2 trillion.

Historically, the dollar’s strength often provided some relief during crises. Investors typically sought refuge in dollar-denominated assets during turbulent times. However, this dynamic may not hold in the next crisis as tariff wars escalate, damaging not just U.S.-China relations but global trade relying on interconnected supply chains. Avoiding unpredictable policy shifts is crucial to minimize the risks of market collapse.

In summary, a market crash today could lead to far more severe economic consequences than the dot-com bust. With greater wealth at risk and limited policy tools to cushion the fallout, the existing structural vulnerabilities make the situation increasingly precarious.

This precarious state of the market has left many investors on edge, keenly observing developments as they unfold.