This week marks a special fundraising effort for Naked Capitalism. So far, we have received contributions from 545 donors committed to aiding our fight against corruption and exploitative actions, especially within the financial sector. We invite you to support our cause through our donation page, where various payment methods such as checks, credit/debit cards, PayPal, Clover, and Wise are available. You can also read about the reasons behind this fundraiser, our achievements over the past year, and our current objective of supporting the new Coffee Break/Sunday Movie features.

An initial explanation is necessary regarding the provocative reference to Nazis in the headline. This allusion serves not to sensationalize but to highlight the formidable legal challenges faced when attempting to hold negligent boards and executives accountable.

The focal point of this discussion is the case Lambinet v. Pötsch. This derivative lawsuit is being pursued on behalf of Volkswagen shareholders against the controlling shareholders and their associates, stemming from the infamous Volkswagen “clean diesel” scandal, in which the company systematically equipped U.S. diesel vehicles with software designed to deceive emissions tests. Here’s a brief overview from Wikipedia:

The Volkswagen emissions scandal, commonly referred to as Dieselgate, erupted in September 2015 after the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issued a notice of violation to Volkswagen Group. The agency discovered that Volkswagen had intentionally programmed its TDI diesel engines to activate emissions controls solely during laboratory testing, allowing the vehicles to conform to U.S. standards while emitting far higher levels of NOx during regular driving. Approximately 11 million cars globally, including 500,000 in the U.S. from model years 2009 to 2015, were implicated.

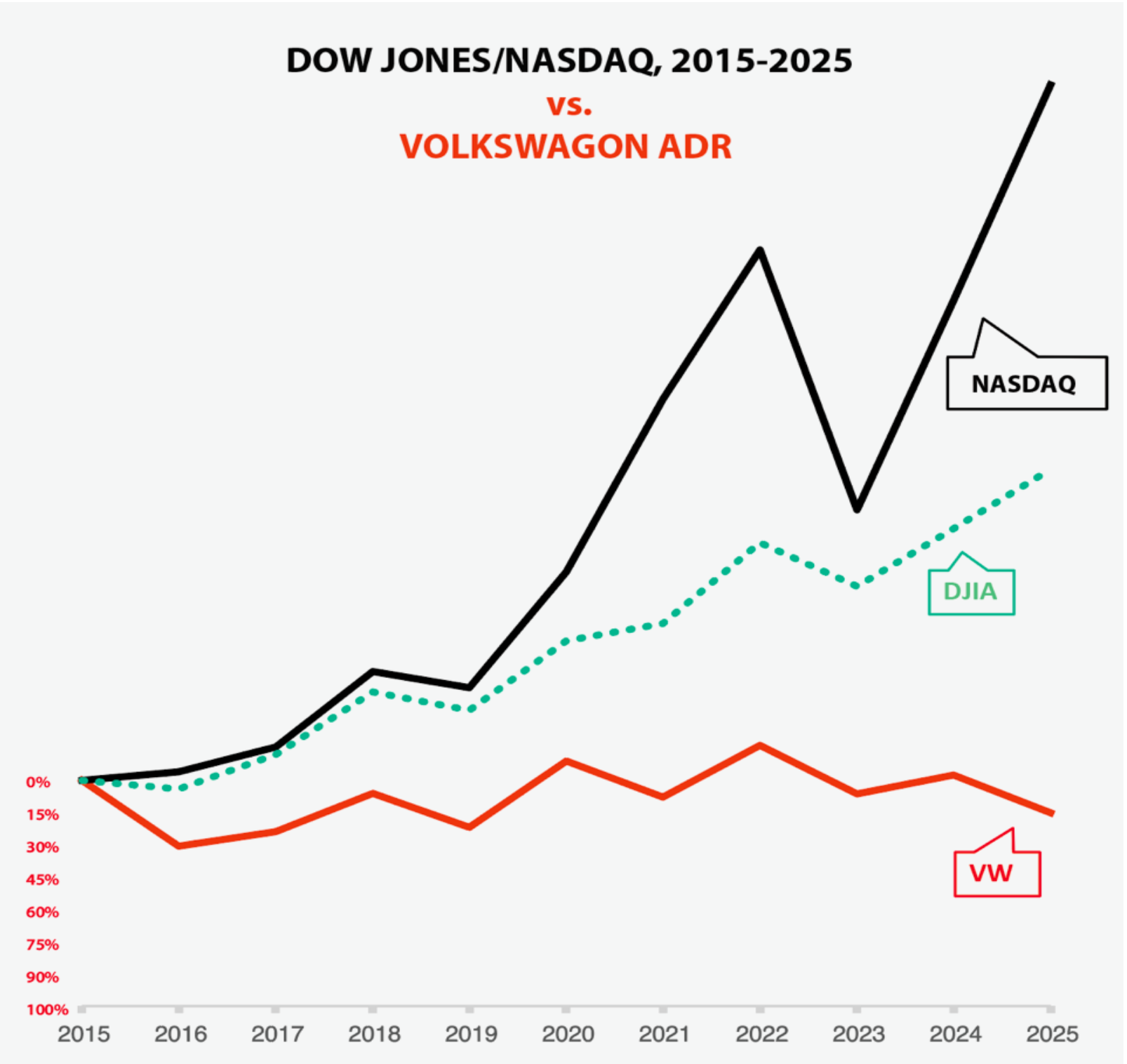

By June 2020, Volkswagen had already incurred costs exceeding $33.3 billion in settlements, buybacks, and other expenses related to the scandal. This substantial financial impact explains why shareholders are seeking redress.

The mention of Nazis in the filings might seem out of place; however, it surfaced as a response to disparaging remarks made against the plaintiffs’ legal counsel. The attorneys—Michelle Lerach and Albert Chang—are notable figures in class-action litigation, previously involved in high-profile cases against prominent firms.

The defendants’ attacks on the plaintiffs’ attorneys opened the door for a pointed counter-argument:

Defendants’ attempts to undermine Plaintiffs’ counsel are not only misguided, but inextricably linked to VWAG’s troubling history. The Controlling Shareholders descend from VWAG’s co-founders, who operated the company as an armaments manufacturer during the Third Reich, utilizing forced labor from concentration camps that led to thousands of deaths. This oppressive corporate culture facilitated the Clean Diesel Scheme and deceived regulators and consumers. While Volkswagen has incurred substantial penalties, the Controlling Shareholders have evaded accountability. This derivative action seeks to rectify that.

This legal document emphasizes procedural matters rather than the substantive issues of the case, yet it effectively underscores the complexities of holding accountable those in positions of power for practices that have caused significant harm.

In legal terms, this involves what is known as “motions practice,” where numerous procedural arguments are introduced. This can prove to be an effective defense strategy, even if the defendants ultimately lose. Delays can benefit the defendants, as crucial witness memories may fade, and key figures may pass away.

To grasp the misconduct, one should initially review the Background section, which starts on PDF page 20/numbered page 6.

Key legal issues include:

The use of a derivative suit. In this type of suit, shareholders take action to assert rights typically reserved for the corporation, which has failed to act in these interests. Often, plaintiffs must establish “demand futility,” demonstrating that attempting to persuade management to act would be pointless. The plaintiffs argue:

The Complaint contains detailed allegations of domination and control by the Controlling Shareholders. Their violations of voting rights are outlined in Plaintiffs’ motions to challenge affidavits. VWAG’s corrupt culture, which has persisted since its Nazi-era origins, enabled the Controlling Shareholders to not only orchestrate the Clean Diesel Scheme but to subsequently cover it up. Their control over the Board, combined with their misconduct constituting “the worst industrial scandal” in history, renders any demand upon the Board futile.

Establishing the conduct of American subsidiaries’ dealings with the parent company. This aspect is crucial for ensuring the key executives are brought before the court. The filing states:

As determined by the AirTran precedent, a subsidiary’s business activities can be imputed to its parent company to ascertain if the parent is “doing business” within New York. Factors include the parent company providing financial support and deriving significant revenue from its subsidiaries. Given these aspects, VWAG is considered “doing business in this state” through its subsidiaries, making it subject to New York jurisdiction.

Proceedings against a German company in a New York court. One argument from the defendants contends that German law should apply to this derivative case. However, the plaintiffs counter that New York law governs because VWAG does conduct business within the state, thus granting courts the authority to adjudicate. This is fundamentally linked to New York’s status as a commercial center ensuring protections for parties engaging in transactions there.

The “internal affairs doctrine” usually allows the law of the state of incorporation to govern a corporation’s internal affairs. While other countries may prefer applying their laws, U.S. courts will enforce the internal affairs doctrine to uphold jurisdiction.

Moreover, the plaintiffs advance:

The defendants’ claims of German law exclusivity fail, as New York courts are empowered by state statute to preside over foreign corporations conducting business in New York. This provides clear grounds for asserting jurisdiction and pursuing legal action against VWAG and its officers.

The forum non conveniens argument. This legal principle is invoked when defendants argue that another jurisdiction would be more appropriate for the case to proceed. However, the idea that the defendants would be inconvenienced by appearing in New York lacks merit, considering their regular business operations in the state.

The case has significant connections to New York, with VWAG extensively involved in the market there, owning numerous dealerships and targeting over 25,000 New Yorkers with altered vehicles.

The defendants also attempted to submit expert testimonies which the plaintiffs claim are inappropriate since they introduce legal conclusions and hearsay, as well as being premature at this case stage. A separate motion to strike these testimonies has been filed.

Establishing personal jurisdiction over the defendants. This entails determining if the court has enough connection to the parties involved for the case to be heard. According to legal principles:

For a court to issue a binding judgment against a defendant, it must possess personal jurisdiction over them. Essentially, this means that a court must have the authority to exert power over a person or entity based on geographical connections.

The plaintiffs assert:

There is no legitimacy to the defendants’ challenges regarding personal jurisdiction. Key individuals frequently traveled to New York for VWAG business, fulfilling requirements for jurisdiction according to state law.

Overall, this filing illustrates the persistent challenges lawyers face when striving for accountability from well-protected corporate officers. If more actions had been taken post-financial crisis, legal precedents could have likely supported private plaintiffs significantly. Yet, there remain dedicated attorneys who continue this vital work.

_______

1 A critical section highlights:

The court should dismiss Bopp’s and Nottebaum’s affidavits as procedurally improper, as they primarily attempt to dispute the truth of the plaintiffs’ claims regarding control over VWAG’s Board. At the pleadings stage, these allegations must be accepted as true. Furthermore, both affidavits rely on hearsay and introduce irrelevant claims. Since the defendants regularly conduct business in New York, claims of inconvenience lack merit.