This is Naked Capitalism’s fundraising week. A total of 996 donors have already supported our mission to tackle corruption and predatory practices, especially in the financial sector. We invite you to join us by visiting our donation page, where you can learn how to contribute via various methods including check, credit card, debit card, PayPal, Clover, or Wise. You can also read about the purpose of this fundraiser, our achievements over the past year, and our current goals, including recognition for our exceptional writers.

Conor here: Trump and artificial intelligence are amplifying a troubling situation in the United States. As the following article discusses, Trump’s proposed “big, beautiful bill” may exacerbate existing issues, especially as a potential government shutdown looms over negotiations.

According to the Consumer Justice Center, debt collection agencies are increasingly utilizing AI technology to enhance their operations. This shift could make it more challenging for consumers to connect with a real person, leading to heightened harassment and a surge in mistakes, including misidentification.

Here are some essential tips from the Consumer Justice Center to safeguard yourself if you find yourself facing medical debt collectors—whether they are relying on AI or traditional methods:

-

Understand your rights. Familiarize yourself with the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act (FDCPA) to know what debt collectors can and cannot legally do.

-

Request written confirmation of any debt. Always ask for documentation before making any payments and do not admit to the debt until you verify its legitimacy, to avoid resetting the statute of limitations.

-

Keep thorough records. Document all interactions with debt collectors, irrespective of whether they are human or automated.

-

Caution with personal information. Be careful about sharing personal details unless you can confidently verify the collector’s identity. Fraudsters often target those who are already stressed about their debts.

By Rae Ellen Bichell, Colorado correspondent for KFF Health News. Bichell was previously a radio reporter for the Mountain West News Bureau and KUNC. This article was originally published at KFF Health News.

Stacey Knoll initially dismissed a court summons as a scam. She had no recollection of receiving medical bills from Montrose Regional Health after an emergency room visit in 2020.

To her astonishment, three years later, her employer received court orders mandating the garnishment of part of her wages to repay a debt of $881—which had escalated to $1,155.26 due to accruing interest and court fees.

The timing could not have been worse. Having just escaped an abusive marriage and secured a safe home, Stacey also gained full custody of her three children and a stable job at a gas station.

“That’s when I received the garnishment from the court,” she shared. “It was terrifying. I had never been on my own, let alone raising kids by myself.”

KFF Health News analyzed 1,200 cases in Colorado where judges authorized wage garnishments due to unpaid medical bills from February 2022 to February 2024. Remarkably, at least 30% of these cases were linked to medical expenses—often even when these bills should have been covered by Medicaid, the public insurance program for low-income individuals or those with disabilities. This figure is likely an underestimate, as medical debt is frequently obscured by other debt types, such as credit card or payday loans. Nevertheless, this percentage would equate to approximately 14,000 cases annually in Colorado where wage garnishments were approved for medical debts.

Additional findings include:

- Patients faced collections for medical bills ranging from under $30 to over $30,000, with most debts averaging less than $2,400. As cases moved through the court system, interest and fees often inflated the owed amount by 25%, with one case surging by over 400%.

- Many individuals were pursued for debts up to 14 years after receiving medical treatment, with collectors often reviving cases as individuals changed jobs.

- Medical bills came from a broad array of providers, including large healthcare systems, small rural hospitals, physician groups, and public ambulance services. Some hospitals even sought to garnish wages from their own employees for medical debts incurred at their facilities.

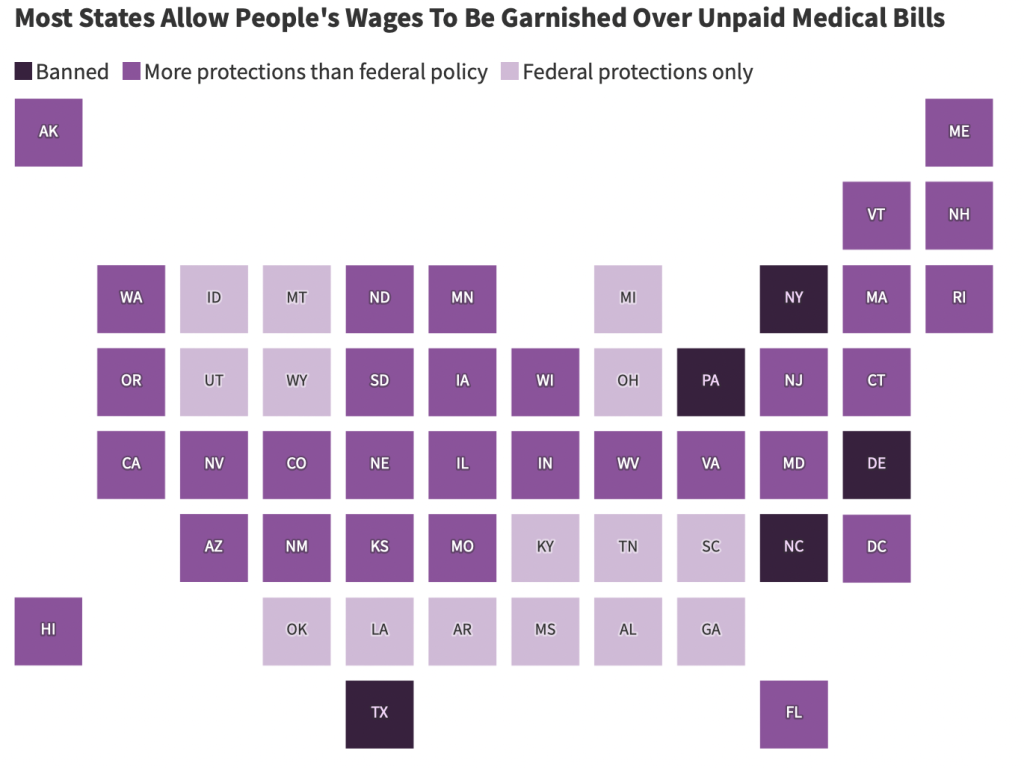

Colorado is not alone in this dilemma. It is one of 45 states that permit wage garnishment for unpaid medical bills. Only Delaware, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Texas have eliminated this practice.

Source: The Commonwealth Fund; Virginia Poverty Law Center. Credit: Lydia Zuraw/KFF Health News

As KFF Health News has reported, medical debt continues to plague millions across the nation. This issue is likely to worsen in the coming years, as millions may lose their health insurance due to changes in Medicaid policies under Trump’s tax and spending legislation. If Congress allows some Affordable Care Act subsidies to lapse, the newly uninsured might soon find themselves in a dangerous cycle of medical debt.

The repercussions will persist: Unpaid medical bills are typically reported on credit histories in most states, especially following a federal judge’s decision in July that overturned a new consumer protection rule.

“If you can’t maintain your health, how can you work to pay off a debt?” questioned Adam Fox, the deputy director of the Colorado Consumer Health Initiative, a nonprofit focused on reducing healthcare costs. “If you can’t afford the bill, wage garnishment will only increase your financial distress.”

Navigating Medical Debt Blindly

When someone fails to settle a bill, the service provider—be it for a car loan, home repairs, or medical services—can pursue legal action. They may also transfer the debt to a collection agency, which can take similar measures.

“Currently, around 1% of working adults are facing wage garnishments,” noted Anthony DeFusco, an economist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. This statistic reflects a significant portion of the population.

However, specific research on wage garnishment stemming from medical debt remains limited. Studies in North Carolina, Virginia, and New York indicate that nonprofit hospitals often resort to wage garnishments from patients who can’t pay, frequently impacting those in low-wage jobs.

Research led by Marty Makary at Johns Hopkins University, prior to his appointment in Trump’s cabinet as the FDA commissioner, labeled this practice as “aggressive.” He co-authored findings revealing that 36% of hospitals in Virginia—predominantly nonprofit and urban—employed garnishment to recover debts as of 2017, affecting thousands.

KFF Health News data suggests that hospitals are not the only entities pursuing patients for wages; the issue is widespread across various healthcare providers.

Researchers and advocates highlight another issue compounding this problem: a lack of court data on these cases obscures the true frequency of wage garnishment. “Debt carries a significant stigma,” stated Lester Bird, a senior manager at the Pew Charitable Trusts. “Much of this takes place in the shadows.”

Without adequate data on how often this occurs, lawmakers are navigating in the dark—despite a 2024 Associated Press-NORC poll indicating that about 80% of U.S. adults support the federal government providing relief for medical debts.

Challenges of Collecting from the Indebted

Colorado has taken steps to reduce the impact of medical debt on credit reports, being among the first of 15 states to do so. Additionally, debt collectors in Colorado cannot foreclose on a patient’s home. If eligible patients opt for payment installments, their payments are capped at 6% of their household income, with remaining debts being forgiven after roughly three years.

However, those who dispute a payment arrangement can face wage garnishment of up to 20% of their disposable income. The National Consumer Law Center has assigned Colorado a “D” grade in terms of protecting family finances.

Consumer advocates express uncertainty about how effectively these regulations are enforced. Many individuals have written to judges explaining that wage garnishment would only exacerbate their dire financial conditions.

“I’m falling behind on my electricity, gas, water, and credit cards,” a Western Colorado resident wrote in a letter to a judge, which KFF Health News acquired as part of their court filings. His case shows he was employed in construction and at a rent-to-own store, struggling with around $8,000 in medical debt and paying close to $1,000 monthly. “At this rate, I’m going to lose everything.”

The individuals examined in KFF Health News’ analysis held diverse jobs ranging from school districts, ranching, and mining to construction and local government roles. Many were employed by retailers like Walmart and Family Dollar, as well as gas stations, restaurants, and grocery stores.

“You’re really exacerbating difficulties for people when they’re already struggling,” said Lois Lupica, a former attorney partnered with the Denver-based Community Economic Defense Project and the Debt Collection Lab at Princeton. “It’s as though you’re trying to extract blood from a turnip.”

In 2022, court records indicated that the Valley View health system in Glenwood Springs was authorized to garnish a patient’s wages over a $400 bill, despite that patient working for a local organization supported by the health system as part of its community benefits. Nonprofit hospitals, such as Valley View, are expected to provide community services, including charity care for patients’ debts.

Stacey Gavrell, chief community relations officer for Valley View, stated that the health system offers interest-free payment plans and care at reduced or no cost to families earning up to 500% above the federal poverty line.

“To be the largest healthcare provider in our rural area, being financially viable is critical for our community’s health,” she noted. “Most patients collaborate with us to find suitable payment plans or seek financial aid.”

The collection agency that pursued the worker in court, A-1 Collection Agency, claims on its website to be understanding: “We recognize that times are tough and finances are tight.”

Pilar Mank, who oversees operations for A-1’s parent organization, Healthcare Management, mentioned that they accept payment plans starting as low as $50 a month and that many hospitals they partner with provide discounts for lump-sum payments.

“Taking legal action against a patient is our last resort,” she said. “We strive to accommodate patients as best as we can.”

In some instances, hospitals have also applied wage garnishments to their employees for care received at their institutions. One such case involved a hospital employee who progressed from housekeeper to registrar and eventually became a quality analyst. Despite actively representing her employer at public events and being featured on the hospital’s website, wage garnishments continued against her for $10,000 in medical expenses.

“Delivering hospital care incurs costs,” remarked Julie Lonborg, a spokesperson for the Colorado Hospital Association, in response to questions about hospitals garnishing their own employees’ wages. “In some respects, I find it amusing to be asked why they don’t pursue garnishments.”

Research indicates that hospitals collect only about 0.2% of their overall revenue through wage garnishments, said April Kuehnhoff, a senior attorney with the National Consumer Law Center, advocating for low-income individuals.

“It’s also worth noting that some states prohibit this entirely,” she added. “Hospitals continue to provide medical services without issue.”

Unequal Burdens: Collectors vs. Patients

Debt buyers profit from purchasing debts from providers who have given up on recovery and then attempting to collect money owed, along with interest. Collection agencies earn a percentage of successful recoveries, with some companies engaging in both activities.

BC Services opted not to make a comment, and Wakefield & Associates did not respond to inquiries.

Charlie Shoop, president of Professional Finance Company, indicated that his organization seeks wage garnishment in fewer than 1% of the accounts placed with it for collection.

In 2024, a new state law mandates that healthcare providers in Colorado cannot disguise their identities when suing individuals for medical debts, a measure prompted by a 9News-Colorado Sun investigation created in collaboration with the Colorado News Collaborative-KFF Health News reporting project.

In various states, the process for filing lawsuits against debtors and securing wage garnishments is often quite straightforward—particularly if the debtor fails to appear in court.

“It’s alarmingly easy,” stated Dan Vedra, a lawyer in Colorado who often supports consumers in debt disputes. “With just a word processor and a spreadsheet, one could generate thousands of lawsuits in a matter of hours.”

Among KFF Health News’ data, nearly all cases involving medical debts resulted in default judgments, indicating that patients did not defend themselves in court. Missing a court date can occur for various reasons, including misunderstanding court tactics, not receiving notices, or failing to take time off work.

Experts like Vedra assert that this high rate of default judgments reflects a system that excessively favors creditors over the indebted, often putting consumers at risk of suffering from unsubstantiated charges.

On the other hand, New Hampshire now necessitates that creditors return to court for each paycheck they wish to garnish, as state regulations permit creditors to garnish only already-earned wages. According to Maanasa Kona, a research professor at Georgetown University, “It may not seem significant on paper, but it becomes impractical for creditors to pursue.”

Pursued for Erroneous Bills

The complexities of the U.S. medical billing system render it susceptible to errors, noted Barak Richman, a law professor at George Washington University and scholar at Stanford Medicine. He has examined medical debt collection practices in various states, concluding, “Bills are often not only difficult to understand but frequently also incorrect.”

Indeed, Colorado’s Health Care Policy & Financing Department, which oversees Medicaid, revealed it sent nearly 11,000 letters in the past fiscal year to healthcare providers and collectors that mistakenly pursued patients enrolled in Medicaid. Medical expenses for such individuals should be billed to Medicaid, with patients typically being required to pay minimal amounts, if anything, for their care.

Shoop pointed out that his sector has unsuccessfully pushed Colorado for access to a database to verify Medicaid coverage status for patients.

Colorado’s Medicaid program declined to make comments on the matter.

Patricia DeHerrera, a resident of Rifle, Colorado, had to provide proof that she and her children were covered by Medicaid when receiving care at Grand River Health. This need arose only after A-1 notified her employer, a gas station chain, with court-approved documents to garnish a portion of her wages.

After contacting the state, DeHerrera received letters notifying both the hospital and the collection agency that they were engaging in “illegal billing actions” and ordered them to cease. Both entities complied.

According to Theresa Wagenman, controller for Grand River Health, if patients present documentation from a Medicaid case manager confirming their eligibility, their bills are removed from the collections process. She also mentioned that patients receive at least eight notifications and a number of phone calls before a collection agency is authorized to proceed with legal action.

DeHerrera’s key advice for others in similar circumstances is: “Be aware of your rights. If not, they will exploit you.”

Nonetheless, contesting bills isn’t straightforward.

Nicole Silva, a resident of Sanford, Colorado, reported that despite her family being enrolled in Medicaid when her daughter suffered injuries in a car accident, her wages were garnished for a $2,181.60 ambulance ride, which escalated to over $3,000 due to interests and court fees.

She attempted to demonstrate the inaccuracy of the bill by contacting her county’s social services office, but found it unhelpful and struggled to connect with the right person at the state level. The Medicaid program confirmed to KFF Health News that her daughter was covered at the time of the incident.

Attempting to resolve this issue was overwhelming for Silva and her husband as they juggled parenting multiple children—one with severe disabilities—and managing work commitments, with her teaching preschool and her husband working as a rancher.

The loss of approximately $500 a month from her wages affected their ability to pay other necessary bills. “It was a choice between groceries or the electric bill,” she mentioned.

When their electricity was cut off, she noted, they had to scramble to borrow money from friends and colleagues to restore it—incurring additional fees in the process.

As a result of this experience, Silva expressed reluctance to call an ambulance in the future.

Fox, of the Colorado Consumer Health Initiative, remarked that consumers often feel powerless to prevent wage garnishments; however, they do have legal recourse and can contest these garnishments in court, highlighting their eligibility for discounted or charity care if treated by a nonprofit hospital.

DeFusco, the economist, argues that filing for Chapter 7 bankruptcy is an underutilized option that halts garnishments immediately—albeit not always indefinitely—and carries its own consequences. He acknowledges the paradox: it’s a complex process that often requires hiring legal counsel.

“To eliminate your debts, you need financial resources,” he pointed out. “And typically, that’s the very reason people find themselves in these predicaments.”