In 2020, when AlphaFold cracked the protein-folding conundrum, it proved that artificial intelligence could address some of biology’s most complex questions: specifically, how a sequence of amino acids organizes into functional molecular machines.

The team at Google DeepMind, responsible for this Nobel Prize-winning initiative, then shifted their focus from protein structures to their functions within biological systems. Utilizing similar machine-learning techniques, they created AlphaMissense, an AI tool designed to predict which alterations in protein structure might lead to diseases. Following this, they introduced AlphaProteo, a system aimed at designing proteins that can interact with specific molecular targets.

Now, the innovators behind the Alpha platform are expanding their scope from proteins to genomics, aiming to uncover how the extensive regulatory regions of DNA influence when, where, and how genes are activated or deactivated.

Introducing AlphaGenome. This tool has been likened to a “Swiss Army knife for exploring non-coding DNA.” It provides a method to systematically analyze the 98% of the genome that doesn’t encode proteins, but instead regulates how these genetic instructions are utilized within cells.

“This enables us to model complex processes… with unprecedented accuracy,” said Žiga Avsec, head of genomics at Google DeepMind, during a press conference introducing the new tool.

Narrowing the Genomic Search Space

However, AlphaGenome does have some limitations. For instance, its training data predominantly come from bulk tissue datasets, which may reduce its accuracy for rare cell types or specific developmental stages, according to Christina Leslie, a computational biologist at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. “The generalization to new cell types is a significant limitation,” she emphasized.

Additionally, it faces challenges in capturing distant interactions when regulatory areas are situated hundreds of thousands to millions of DNA base pairs away from their target genes, Leslie pointed out.

Despite these obstacles, this model is assisting scientists in prioritizing genetic variants that are likely significant, effectively narrowing down potential candidates from the entire genome to a manageable set of testable hypotheses. “It is the current state of the art,” states Leslie.

According to DeepMind, thousands of researchers worldwide are utilizing AlphaGenome, which is available for free on GitHub for academic research purposes. It is being applied to various fields, including identifying genetic factors behind cancer and rare diseases, discovering new drug targets, and designing synthetic DNA strands with specialized regulatory functions.

“It’s exciting to see tools like AlphaGenome emerge and outperform prior dedicated algorithms that were focused on different genomic aspects,” remarks Richard Young, a biologist at the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research who has collaborated with Google DeepMind on its AI co-scientist platform, though he was not involved in AlphaGenome. “It’s a significant accelerator.”

High Resolution at Large Genomic Scale

The launch of AlphaGenome signifies a further advancement in AI’s progress in tackling some of biology’s most persistent and impactful problems.

For DeepMind, there’s also clear commercial logic. The company’s expanding portfolio of biological models—covering protein structure, mutations, generation, and now genomic regulation—creates a vertically integrated platform for molecular prediction. This platform is expected to facilitate new diagnostic capabilities and therapeutic strategies, according to Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of science and strategic initiatives at Google DeepMind.

“All these diverse models address critical problems relevant to understanding biology,” Kohli asserts.

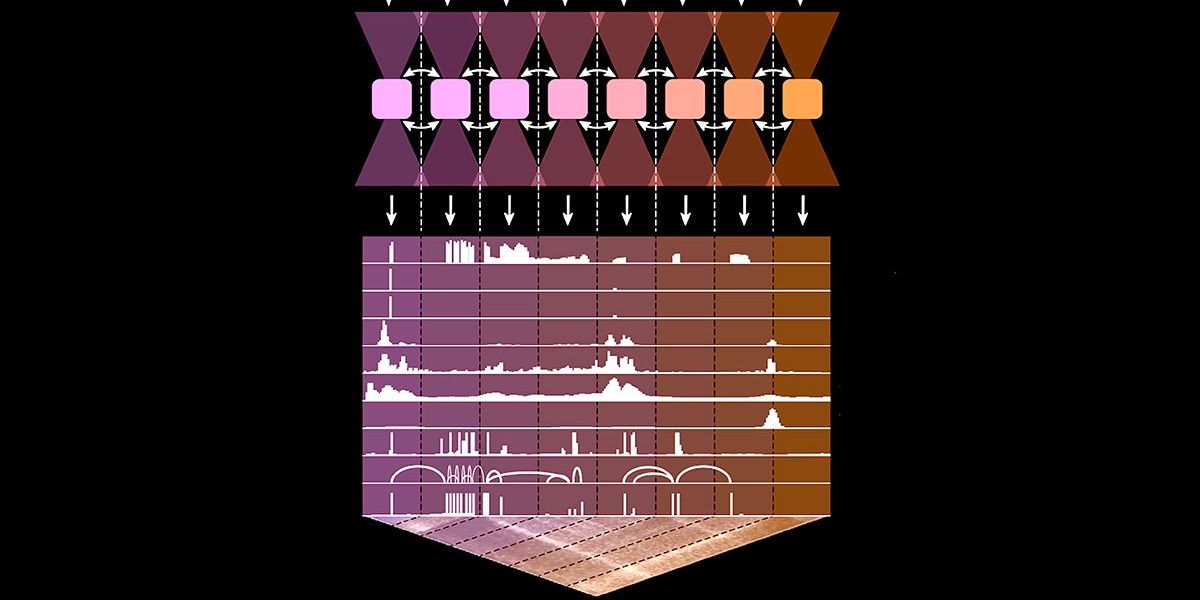

AlphaGenome stands as the newest—and most comprehensive—component of this strategy. Trained on raw DNA, the model can predict 11 types of biological signals that determine how genes operate within cells. These include whether a gene is activated or repressed, where gene activity initiates, how genetic messages are modified, how tightly DNA is compacted, which regulatory proteins bind to it, and how distant genomic regions interact with one another.

Many of these features are already addressed by specialized AI tools—like SpliceAI for splice site prediction, ChromBPNet for chromatin accessibility, and Orca for three-dimensional genome structure. However, these tools are usually employed separately, necessitating researchers to synthesize results from multiple sources.

“AlphaGenome resolves this fragmentation into a more cohesive framework, which is not only more user-friendly but also accelerates scientists’ workflows,” says Natasha Latysheva, a computational geneticist at Google DeepMind.

While earlier attempts have sought to encompass numerous regulatory effects within a single model, past architectures like Borzoi and Enformer often exchanged fine-grained resolution for breadth of biological coverage.

AlphaGenome seeks to avoid this compromise. The model can process up to one million DNA base pairs concurrently, maintaining long-range regulatory context while still providing single-base-pair resolution predictions. Practically, this capability allows it to examine how shifts in one nucleotide may impact extensive regions of the genome.

Connecting DNA Changes to Disease Biology

The paper detailing the new model showcases several instances of this capability.

In one case, AlphaGenome accurately forecasted how a small deletion disrupted a splice site in a gene related to blood vessel formation, leading to diminished RNA production. In another instance, it highlighted how mutations near a cancer-associated gene enhanced its activity, contributing to aggressive leukemia.

Whether this predictive ability generalizes to less-studied genes remains an open question.

“This is undoubtedly a potentially valuable tool—but it’s just that, a tool,” says Charles Mullighan, deputy director of the St. Jude Children’s Research Comprehensive Cancer Center. “It’s not the final answer, but it will be instrumental in providing insights that can guide further functional analyses and experiments.”

One unique characteristic of the system, notes Latysheva, is its tendency to favor false negatives over false positives, meaning it’s more inclined to overlook a genuinely significant DNA variant than to incorrectly identify a harmless one. “However, the upside is that when it predicts a substantial effect, it tends to be very accurate,” she says. Thus, when the model presents a strong prediction, “you can trust it has a reasonable level of confidence.”

This reliability proved advantageous for Y-h. Taguchi and Kenta Kobayashi at Chuo University in Japan. As early adopters of AlphaGenome, these bioinformatics researchers employed the AI tool as an independent verification, confirming that genes associated with sleep deprivation were notably active in their neurons of interest—just as their prior analysis of gene-expression data had anticipated.

“AlphaGenome succeeded in the cross-validation,” states Takuchi, who published the findings on January 1 in the journal Genes.

This kind of validation highlights AlphaGenome’s significance. Similar to AlphaFold, the system is not designed to elucidate biology in its entirety but rather to simplify the exploration of its most complex areas.

From Your Site Articles

Related Articles Around the Web