The recent heist at the Louvre Museum is causing a stir across the globe, with its implications reverberating in the art world and beyond. Two suspects have been apprehended, and there are whispers of inside help. As the investigation unfolds, the fate of the stolen treasures remains unclear, raising questions about the dark intricacies of art theft.

Conor here: French media reported yesterday that two suspects from the impoverished Paris suburb of Seine-Saint-Denis have been arrested, with indications they may have been assisted by a security guard at the Louvre. There’s currently no information on the location of the Crown Jewels, whose theft some have alarmingly equated to the fire at Notre-Dame Cathedral in 2019.

Following the news about the Louvre theft, commenters discussed in Links the possibility that the thieves could have been acting on behalf of an affluent “collector.” If their goal was merely jewels and gold, targets with less notoriety would seemingly be simpler to access. The following piece delves deeper into the world of stolen art.

By Leila Amineddoleh, Adjunct Professor of Law at New York University. Originally published at The Conversation.

The high-profile heist at the Louvre in Paris, which unfolded on October 19, 2025, resembled a cinematic escapade: a group of burglars making off with an array of magnificent royal jewels displayed in one of the world’s most renowned museums.

However, with law enforcement eagerly pursuing them, the robbers face a daunting question: How will they monetize their stolen bounty?

Statistics reveal a grim reality: the majority of stolen works of art are never recovered. In my art crime classes, I often highlight that the recovery rate is below 10%. This is particularly concerning given an estimated 50,000 to 100,000 artworks are reported stolen annually worldwide, predominantly from Europe, with the true figure likely higher due to lack of reporting.

That said, turning a profit from stolen artworks is a complex endeavor. The specific items pilfered from the Louvre—eight pieces of invaluable jewelry—may, however, provide these thieves with an advantage.

A Narrow Market of Buyers

Unlike paintings, which are challenging to sell legally, stolen art can’t be easily transferred since thieves can’t establish “good title,” the legitimate ownership rights of an item. Furthermore, no respected auction house or art dealer would knowingly sell stolen works, and responsible collectors avoid purchasing such property.

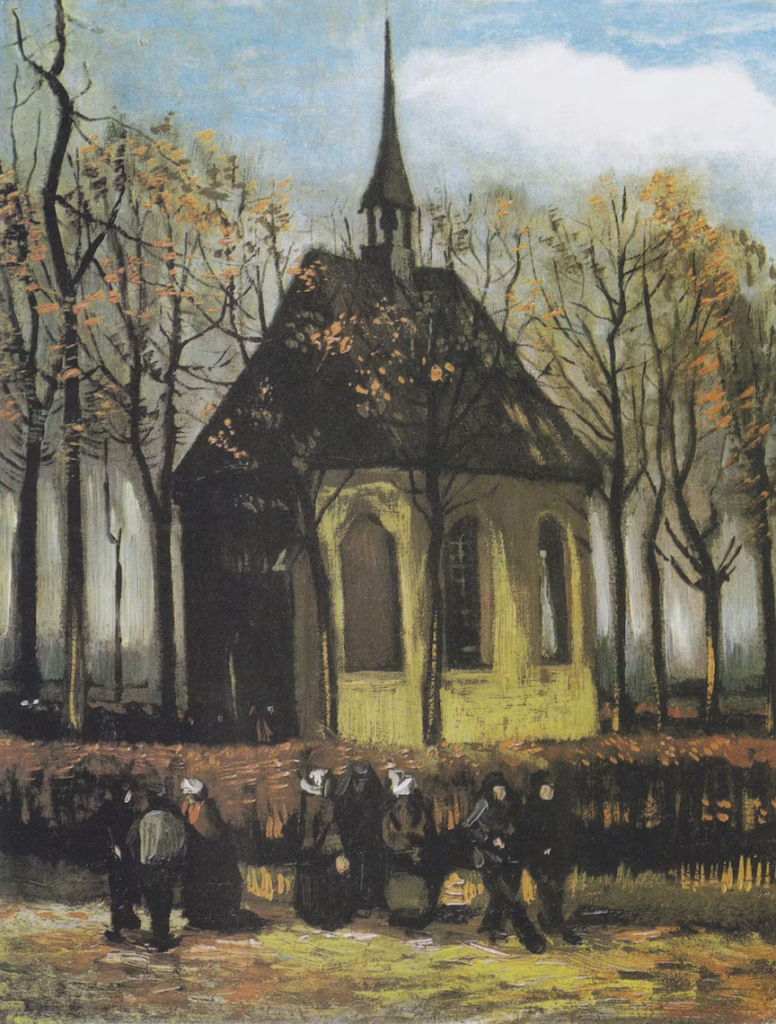

Nevertheless, stolen paintings still hold potential value. In 2002, intruders broke into Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum via the roof, absconding with “View of the Sea at Scheveningen” and “Congregation Leaving the Reformed Church in Nuenen.” In 2016, Italian police retrieved these relatively unscathed paintings from a Mafia hideout in Naples. Though it remains unclear whether the Mafia purchased the artworks, it’s common for criminal organizations to retain valuable items as collateral.

Van Gogh’s 1884-85 oil on canvas painting ‘Congregation Leaving the Reformed Church in Nuenen’ was one of two works stolen from Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum in 2002. Van Gogh Museum

Occasionally, stolen art ends up in collectors’ hands unwittingly. In the 1960s, an employee of the Guggenheim Museum took a Marc Chagall painting from storage, and the theft went unnoticed until an inventory was done years later. Unable to locate the piece, the museum eventually removed it from its records.

Meanwhile, collectors Jules and Rachel Lubell purchased the artwork for $17,000 from a gallery. When the couple requested an auction house to appraise the work, a former Guggenheim staff member at Sotheby’s recognized it as the missing piece.

Guggenheim sought its return, ultimately leading to a contentious court battle. Eventually, the matter was settled, and the painting was repatriated after an undisclosed amount was paid to the collectors.

Some buyers, however, knowingly purchase stolen art. Following World War II, purloined works circulated across the market, with buyers fully aware of the rampant looting taking place in Europe.

Subsequently, international laws were enacted to facilitate the recovery of looted art by original owners, even years later. In the U.S., law also permits descendants of the original owners to reclaim stolen works provided they can substantiate their claims.

Jewels and Gold Easier to Monetize

Unlike paintings, the stolen items from the Louvre included bejeweled artifacts: a sapphire diadem, a necklace and single earring from a matching set associated with 19th-century French queens Marie-Amélie and Hortense, an exquisite matching set of earrings and a necklace once belonging to Empress Marie-Louise, Napoleon Bonaparte’s second wife, a diamond brooch, along with Empress Eugénie’s diadem and her corsage-bow brooch.

These meticulously crafted historical pieces possess immense cultural significance. Even if each item were dismantled and sold for parts, they would retain substantial value. Thieves could sell the precious gems and metals to dishonest dealers and jewelers, who would reshape them for resale. Even at a fraction of their original worth—the amount received from illegally obtained art is typically much lower than that for legally acquired pieces—the gems would still equate to millions of dollars.

While shifting stolen goods on the legitimate market proves challenging, an underground market exists for looted art. Pieces might be traded in secretive settings, during private meetings or even via the dark web, protecting the identities of participants. Studies have shown that stolen—and sometimes forged—artwork and antiquities frequently surface on mainstream e-commerce platforms such as Facebook and eBay. Once a sale is completed, the vendor may erase their online profile and vanish.

A Heist’s Sensational Allure

While films like “The Thomas Crown Affair” portray glamorous heists executed by charming rogues, the reality of art crime is typically far more mundane.

Art theft often occurs as a crime of opportunity, usually in less monitored spaces like storage units or during transit.

Most significant museums and cultural institutions do not exhibit their entire collection at once. Instead, numerous works remain in storage. Less than 10% of the Louvre’s collection is on display simultaneously—around 35,000 out of 600,000 objects—with many pieces unseen for years, if not decades.

This leads to potential unintentional loss, such as the case of Andy Warhol’s rare silkscreen “Princess Beatrix,” which was likely accidentally discarded during renovations of a Dutch town hall, along with 45 other works, or simply stolen by staff. According to the FBI, around 90% of museum heists are perpetrated by insiders.

Interestingly, just days prior to the Louvre incident, a Picasso painting valued at $650,000, “Still Life with Guitar,” vanished while being transported from Madrid to Granada. The piece was part of a shipment featuring several works by the Spanish artist, yet it was missing upon opening the packages. This incident drew far less public interest.

In my view, the thieves’ biggest blunder was not simply dropping the crown they lost or discarding the vest they wore, both of which left clues for law enforcement.

Instead, it was the audacity of the heist—one that captured global attention, ensuring that French detectives, private investigators, and international law enforcement will remain vigilant in uncovering any new gold, gems, or royal artifacts that surface for sale in the coming years.