In the face of ongoing climate challenges, the upcoming international climate negotiations in northern Brazil will shine a light on the critical intersection of food, agriculture, and environmental policy. As representatives from nearly every nation gather from November 6-21 in Belém—an Amazon gateway—there’s hope for meaningful reform in food systems, which significantly contribute to carbon emissions. Advocates are eager to see if this thirtieth Conference of the Parties (COP30) can serve as a turning point for policy-driven change.

By Rachel Sherrington and Hazel Healy. Originally published at DeSmog Blog

Food and agriculture will be a focal point at the upcoming round of global climate discussions. From November 6-21, representatives from around the world will convene in Belém, northern Brazil, where most countries are falling short in their commitments to reduce carbon emissions—essential for mitigating the grim impacts of climate change.

Various food and climate organizations are optimistic that this thirtieth annual Conference of the Parties (COP30) can be a significant opportunity for reforming food systems, which account for approximately one-third of global greenhouse gas emissions.

Brazil, the host nation and COP30 presidency, is known for its diplomatic prowess and has prioritized agriculture as the third objective on the conference agenda.

President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva has made strides at home, lifting millions out of hunger while committing to the protection of endangered ecosystems in the Amazon and Cerrado regions. Additionally, with Brazil ranking as the world’s eleventh largest economy and a major agricultural player, it features both multi-billion-dollar beef and grain exporters and state-supported family farms that are vital to the national food supply.

However, those advocating for transformative change in food systems will face robust opposition from entrenched interests, particularly Brazilian agribusiness, which has been mobilizing their influence throughout 2025.

The agriculture sector is under increasing scrutiny and pressure to enhance its practices. It is a significant source of various damaging and potent climate-warming emissions—from nitrous oxide released by fertilizers to the mounting methane emissions due to the digestive systems of the world’s 3.5 billion cattle, sheep, and goats.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has emphasized that effective climate action must include significant reductions in emissions from food and agriculture. In particular, “Big Meat” is under the spotlight as nearly a third of global methane emissions can be traced back to this sector.

Campaigners label efforts to reduce agricultural methane emissions—outpacing those of the oil and gas sector—as “the quickest and most cost-effective way to slow warming in our lifetimes.” Scientific evidence suggests that minimizing red meat consumption, especially in wealthier nations, is the best strategy to achieve this goal.

At COP30, agribusiness representatives will assert that they are part of the solution to tackling climate change. They will downplay the adverse impacts of agriculture, advocate for elusive technical solutions that fail to reliably reduce emissions, and portray mandatory regulations as detrimental to human health and well-being.

In a positive move, the Brazilian COP presidency has championed “Information Integrity” at this summit to combat the wave of climate misinformation. Yet, greenwashing in agriculture can be much harder to detect.

Here are eight prevalent arguments to anticipate in Belém:

Regenerative Agriculture

Commonly associated with: grass-fed beef, regenerative grazing, carbon farming, carbon positive

The term “regenerative agriculture” broadly encompasses environmentally friendly farming practices aimed at increasing carbon storage in soil. However, it is often devoid of standardized definitions, making it a favorite buzzword among companies such as McDonald’s and Cargill in their net zero campaigns.

It’s central to no fewer than 27 panels planned for the climate summit’s “Agrizone Pavilion,” coordinated by Embrapa, Brazil’s public agricultural research body, and sponsored by Nestlé and Bayer, a major pesticide company.

While practices loosely classified as “regenerative,” including organic farming and no-till techniques, offer some benefits such as long-term carbon sequestration in soil and enhanced biodiversity, scientific research shows that the potential of soil carbon sequestration is minimal compared to the sector’s emissions.

Particularly in the beef industry, claims that regenerative grazing and manure management can dramatically reduce carbon emissions are misleading since their emissions levels rival those of entire nations, like India.

During past climate summits, industry groups, such as the Protein Pact, have pointed to environmental achievements of flagship ranches to equate intensive cattle farming with sustainability and environmental care, yet the industry’s contribution to methane emissions effectively undermines such claims.

A 2024 survey of 200 experts published by the Harvard Animal Law and Policy Program found that 85 percent concur that “animal-sourced” foods must decrease in wealthy and middle-income countries to achieve a 50 percent reduction in livestock’s greenhouse gases by 2050, aligning with climate goals set in Paris.

It’s worth noting that promoting regenerative practices presents financial incentives for agribusiness, especially as adjustments to the Paris Agreement permit “soil-based credits” to be sold in UN carbon markets.

Tropical Agriculture

Frequently linked with: regenerative agriculture, climate-neutral, carbon offsets

Brazil’s “special envoy for agriculture,” Roberto Rodrigues, will arrive at COP30 prepared to convince negotiators that Brazil can lead the charge in “low-carbon tropical agriculture.”

This approach suggests that warm-region soils and afforestation can absorb enough carbon to counteract the methane emissions produced by Brazil’s cattle population, which numbers approximately 195 million.

In the lead-up to the summit, key agricultural polluters have championed tropical agriculture to support their “carbon neutral” claims. Brazilian meat giant JBS, for instance, reported higher methane emissions in 2024 than ExxonMobil and Shell combined.

This notion is largely backed by Brazil’s state research agency, Embrapa, through its “low-carbon” and “carbon-neutral” beef labels, which now play a pivotal role in industry marketing.

Independent research demonstrates that soil cannot absorb enough carbon to counterbalance livestock emissions in the region. “While emissions can be mitigated,” says leading soil scientist Pete Smith, “claims that soil carbon can significantly offset emissions are unfounded and unverified.”

Other experts have disputed elements of Embrapa’s methodology, noting that it often overlooks the fact that Brazilian pastures are established by clearing forests, a process that releases more CO₂ than new trees can recapture.

Claudio Angelo, from the Climate Observatory, a coalition of climate NGOs, recognizes that while Brazilian farming is undergoing improvements that could sequester carbon on a limited scale, labeling the sector as highly sustainable is “intellectual dishonesty,” a sentiment he shared with Bloomberg.

Angelo emphasizes the broader situation. Brazil’s methane emissions have risen by 6 percent since 2020, with agriculture responsible for over 74 percent of total emissions in 2023. Additionally, the expansion of croplands and cattle farms has contributed to the decimation of 97 percent of native vegetation in recent years.

Advocates of tropical agriculture often assume their sector can continue growing sustainably, but they diverge from scientific consensus. A September 2025 article published in One Earth described current trends in the food system as presenting an “unacceptable risk,” advocating for dietary changes to avert crucial tipping points that could render ecosystems like the Amazon rainforest and coral reefs unsalvageable.

To meet the Paris Agreement targets, significant cuts in livestock production and a drastic reduction in animal-sourced food consumption are necessary,” stated Harvard University climate and food systems expert Helen Harwatt. Notably, Brazilians consume 20 percent more beef than Americans, despite the U.S. being a leading beef producer. This necessitates a “massive reduction in beef consumption,” she noted, contributing to the Harvard Animal Law and Policy Program’s report.

Yet, based on a recent position paper from the Brazilian Agribusiness Association (ABAG), it seems agribusiness may promoting its sector as a “low-carbon agriculture leader” without discussing necessary livestock reduction.

Envoy Rodrigues is advocating for an initiative allowing Brazil and similar countries to account for carbon sequestration in soil from tropical agriculture within their emissions reports.

In response to inquiries, Embrapa stated that “emissions related to deforestation are factored into the carbon calculator over a 20-year timeline,” asserting that their protocols on low-carbon and carbon-neutral production are based on established science.

No Additional Warming

Commonly tied to: climate neutrality, GWP*, tropical agriculture

Discussions at Belém are likely to feature GWP*—“global warming potential star”—as nations with longstanding, polluting livestock industries seek favorable measurement methodologies for methane emissions. GWP* serves to compare the growth of short-lived gases like methane against long-lived CO2, but it becomes contentious when used by countries or companies to significantly understate their own emissions, particularly in substantial meat and dairy sectors, while lighter increases elsewhere are penalized.

Powerful industry groups from the U.S., Australia, and Latin America, along with the metric’s originator, Oxford academic Myles Allen, are proponents of GWP*. For the first time this year, governments—including New Zealand—are enshrining GWP* into domestic climate goals, effectively softening their methane reduction targets.

Critics have labeled these methodologies as an “accounting trick” and “fuzzy methane maths,” claiming they will mask rising methane emissions. According to environmental economist Caspar Donnison, declaring climate neutrality under GWP* is akin to “claiming you’re fire-neutral because you’re pouring slightly less petrol on the blaze.”

A global coalition of climate scientists has recommended against adopting GWP* as a common metric, arguing it “creates an impression that current elevated methane emissions are permissible.” Oxford’s Allen referred to COP30 as a chance to “reframe climate policy” around alternative metrics like GWP*. In his response to inquiries, he stated, “climate claims should certainly be informed by their impact on global temperature, and I don’t mind how that’s calculated—provided it’s done accurately.”

Brazilian agribusiness groups are seizing on the GWP* as part of their toolkit and gaining support from Embrapa for this metric.

Bioeconomy

Often linked with: circular economy, biogas, biofuels, socio-bioeconomy

Similar to regenerative agriculture, the term “bioeconomy” represents various concepts for reshaping production and consumption to harmonize economic growth with nature.

Yet, this term has evolved in Brazil and Europe, becoming a byword for green growth, embraced by agribusiness and governmental entities. Critics argue this shift serves to greenwash the expansion of unsustainable farming practices.

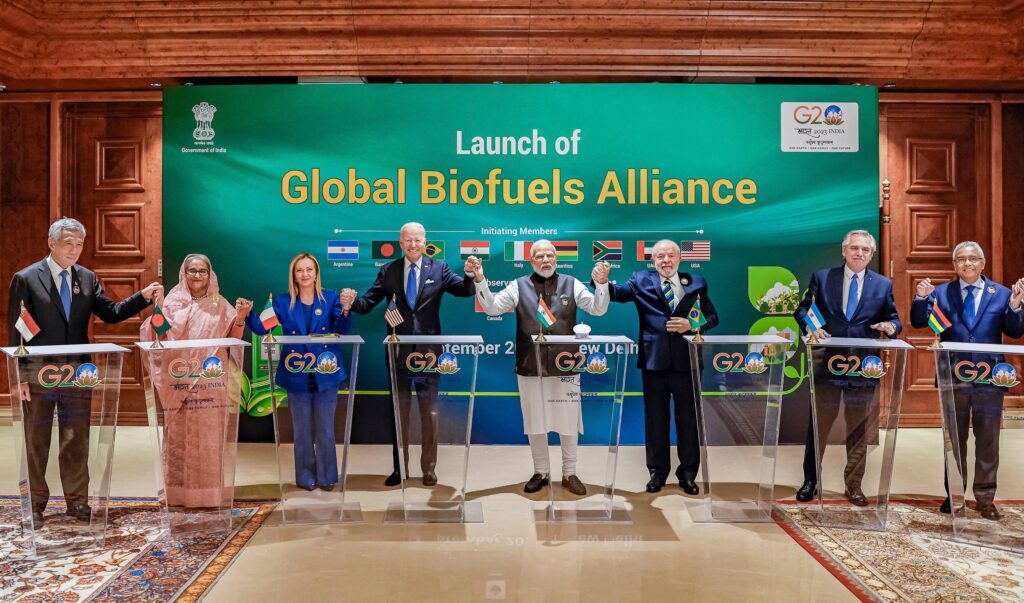

Corporations like Cargill and dairy firm Arla have transformed the bioeconomy into a banner for controversial “green” fuels like biofuels, derived from organic materials. Biofuels encompass a range of liquid fuels produced from biomass, including corn-based ethanol and biodiesel from soy oil. In the U.S., animal fats also enter the biofuel mix.

Environmental advocates have criticized biofuels, which necessitate large portions of land for monoculture crop production, potentially causing deforestation, biodiversity loss, and competition with food crops.

Companies such as JBS and Cargill are also delving into biogas, which captures methane from sources like manure and decaying crop waste. Proponents position biogas as a clean energy alternative to natural gas, though feasibility at an industrial scale remains unclear—one study suggests it could only replace about seven percent of gas-fired power.

Nonetheless, biofuels, regardless of their organic origin, emit greenhouse gases upon combustion. A recent study by Transport and Environment indicated that biofuels emit 16 percent more CO2 than the fossil fuels they are intended to replace, a result of their cultivation impacts.

As a leading producer of sugarcane ethanol, Brazil will prioritize bioenergy initiatives during the climate summit. According to a leaked document obtained by The Guardian, Brazil aims to advocate for a global commitment to quadruple the use of what it deems “sustainable fuels,” particularly biofuels and biogas.

We Feed the World

Commonly linked with: efficiency, emissions intensity, Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), nutrition, “Brazil is only just off the hunger map”

The meat industry’s rhetoric, emphasized in its lobby strategy for COP28 in Dubai, is set to return at COP30, especially as Brazil prepares to unveil the “Belém Declaration on Hunger and Poverty.”

Agribusiness will leverage this narrative to suggest that regulating the industry in alignment with science-based recommendations threatens to exacerbate hunger.

Yet this argument overlooks a critical fact: The world currently produces 1.5 times the food needed, with hunger as an issue rooted in waste, inequality, and poverty—all exacerbated by climate change.

Political will and sound policy—not increased production—are the keys to resolving hunger. While livestock farming is essential for nutritious diets in some parts of the globe, research demonstrates that expanding industrial meat and dairy has minimally improved food security in lower-income nations; rather, it fuels overconsumption in wealthier areas, where excessive meat (especially red and processed) is linked to health issues.

About 50 percent of maize and 75 percent of soy are allocated to animal feed rather than human consumption. Climate scientists, alongside the EAT-Lancet Commission, advocate for reducing meat production in affluent countries to reallocate vast amounts of farmland for grains and pulses that could nourish many more people with lower emissions.

A study from 2016 indicated that smallholder farms produce over 70 percent of calories in regions where hunger is most prevalent, such as Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa, and Southeast Asia.

Brazil’s exit from the UN hunger map—a significant milestone—was largely a consequence of local food policies and investments in support of small farmers rather than agribusiness exports.

The EAT-Lancet Commission proposes diets rich in whole grains, legumes, and seeds for protein, recommending an average 50 percent reduction in red meat consumption across most regions of the globe.

Further research supports that lower meat consumption could yield a global win-win-win scenario by mitigating climate pollution, preserving biodiversity, and enhancing human health.

As the ramifications of climate change escalate, the pressing challenge, according to University of Texas professor Raj Patel, is how to channel resources into more resilient and diverse agroecological systems, which currently receive far less funding than industrial agriculture, rather than perpetuating factory farming under the guise of addressing world hunger.

Big Ag Is Progress and Development

Often coupled with: economic development, Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

The Brazilian agribusiness sector presents a narrative that resonates on cultural platforms, as evidenced by “agronejo”—a fusion of country music with hints of hip-hop and electronic pop—portray agriculture as synonymous with wealth and success. This genre exemplifies a cultural public relations campaign where agribusiness leverages media, including dedicated TV channels and educational materials, to cultivate empathy for producers, particularly among younger audiences.

As COP30 approaches, JBS has taken a proactive role in sponsoring climate conference discussions across prominent Brazilian newspapers, such as Valor Economica and El Estadao, portraying agribusiness as a modernizing force within the global South. For example, JBS’ recent expansion into Nigeria claimed it would create jobs and enhance food security, although local experts dispute this assertion.

Conversely, small producers in the global South are often portrayed as primitive and less productive compared to the industrial operations that claim lower emissions per kilogram of output.

This sweeping narrative shifts the focus away from the overall greenhouse gas emissions associated with industrial agriculture, neglecting the fact that high-income nations contribute the majority of climate pollution, overshadowing the 10 percent of emissions attributed to low-income regions.

Evidence shows agribusiness assertions about wealth and job creation often falter; a 2025 study has shown that despite farmers in the global South producing 80 percent of globally consumed food, profits are largely captured by governments and companies in the global North, predominantly through high-profit activities entailing marketing and distribution.

In the lead-up to COP30, small farmers are dubbing the summit “the agribusiness summit,” while Brazilian civil society is hosting a People’s Summit, providing a counter-narrative to agribusiness’s focus on high-tech solutions, advocating instead for locally sourced foods and the role of ecologically minded smallholder farmers in addressing Brazil’s food needs.

Efficiency Is Enough

Commonly associated with: emissions intensity, innovation, new technologies, producing “more with less”, “We feed the world”

By claiming to produce “more with less,” they assert that carbon emissions can decline while milk and butter yields continue to rise, relying on innovative technology to reduce the “emissions intensity” of dairy production.

Yet, upon scrutiny, many ambitious carbon reduction targets announced by dairy companies focus on intensity measures rather than absolute pollution reductions, which continue to grow. Recent industry data revealed that, between 2005 and 2015, while emissions intensity decreased by 11 percent, total dairy industry emissions increased by 18 percent due to a nearly one-third growth in herd sizes.

Companies like Danish giant Arla, New Zealand’s Fonterra, and China’s Mengniu have set Scope 3 (supply chain) emissions reduction targets based purely on an intensity basis exclusively.

Without production limits—which the agriculture sector is intent on avoiding—there’s no assurance that greater efficiency will correspond to reduced pollution levels. In fact, increasing efficiency often necessitates more use, reinforcing the phenomenon known as the Jevons paradox. For example, while dairy farms in Ireland may exhibit reduced pollution per unit of milk produced, increased production has resulted in growing herd sizes and, consequently, higher methane emissions.

Notably, the influence of the livestock lobby is apparent in the latest FAO report, which lists “technology” and “voluntary efficiency” as primary solutions to the climate crisis, enabling the sector to maintain its growth trajectory. This report has elicited criticism for neglecting peer-reviewed research advocating for policies that encourage dietary shifts away from animal products, with technology positioned as a secondary factor.

Pesticide and fertilizer companies also use efficiency arguments, touting drones, precision spraying, and chemical inputs as environmentally friendly solutions—however, these agrochemicals are primary drivers of ecological collapse and pollution, particularly in relation to extensive monocrop production central to industrial animal agriculture.

While incremental efficiency improvements have value, they cannot substitute absolute reductions in methane, fertilizer usage, and land conversion. Efficiency may favor business interests, but it offers little for the planet.

Fossil Fuels Are the Real Problem

Frequently associated with: “Agriculture is a solution,” “Agriculture is unfairly villainized,” “We are making significant strides in reducing our emissions”

When confronted with agriculture’s impact on climate, farm lobbies have a historical precedent of deflecting to other sectors as scapegoats.

Ahead of the climate summit, Latin American trade organizations are attempting to shift blame onto the fossil fuel industry. One major group has criticized the recent focus on agriculture over more obvious sources of emissions.

The Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture (IICA)—representing significant producer countries—has stated its intention to “remove agriculture from the dock of the accused” during the summit. Deputy Director General Lloyd Day has argued, without discrediting agriculture’s impacts, that the sector has been wrongly labeled a “villain” in climate discussions.

This strategy mirrors techniques employed by other industries, including fossil fuel and tobacco, which have historically sought to downplay their own emissions compared to those in agriculture. The agriculture sector accounts for at least 15 percent of all global fossil fuel consumption for fertilizers, transportation, plastics, and animal feed.

Although fossil fuels are the leading causes of climate change, food systems’ unchecked emissions risk pushing global temperatures beyond 1.5°C.

The food industry now bears the distinction of being the most significant driver of violations of planetary boundaries, contributing to deforestation, wildlife population decline, and freshwater pollution.

Moreover, agriculture outpaces fossil fuels in levels of methane and nitrous oxide emissions, which combined account for over a third of total global warming effects to date.

By placing fossil fuels as the “real villain,” the agriculture sector diverts focus from its substantial environmental footprint and halts effective reform efforts. Climate experts emphasize that combating global warming necessitates addressing both sectors with significant ambition.

JBS, PepsiCo, McDonald’s, and the New Zealand Government did not respond to requests for comment prior to publication.

Additional reporting by Gil Alessi and Maximiliano Manzoni