Federal food guidelines have recently undergone a significant revision, sparking considerable debate. The new recommendations, introduced by United States Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., now emphasize the inclusion of full-fat milk, steak, and butter. This marks a notable shift from earlier dietary suggestions. “We are putting an end to the war on saturated fats,” Kennedy announced during a recent press conference.

However, the updated guidelines also assert that saturated fats should comprise no more than 10 percent of total daily caloric intake, echoing previous recommendations from both the federal government and the World Health Organization. This contradiction raises confusion about the promoted food choices, potentially leaving Americans feeling perplexed in the dairy and meat sections of their grocery stores. Additionally, these guidelines will shape federal food assistance programs, including school meals and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).

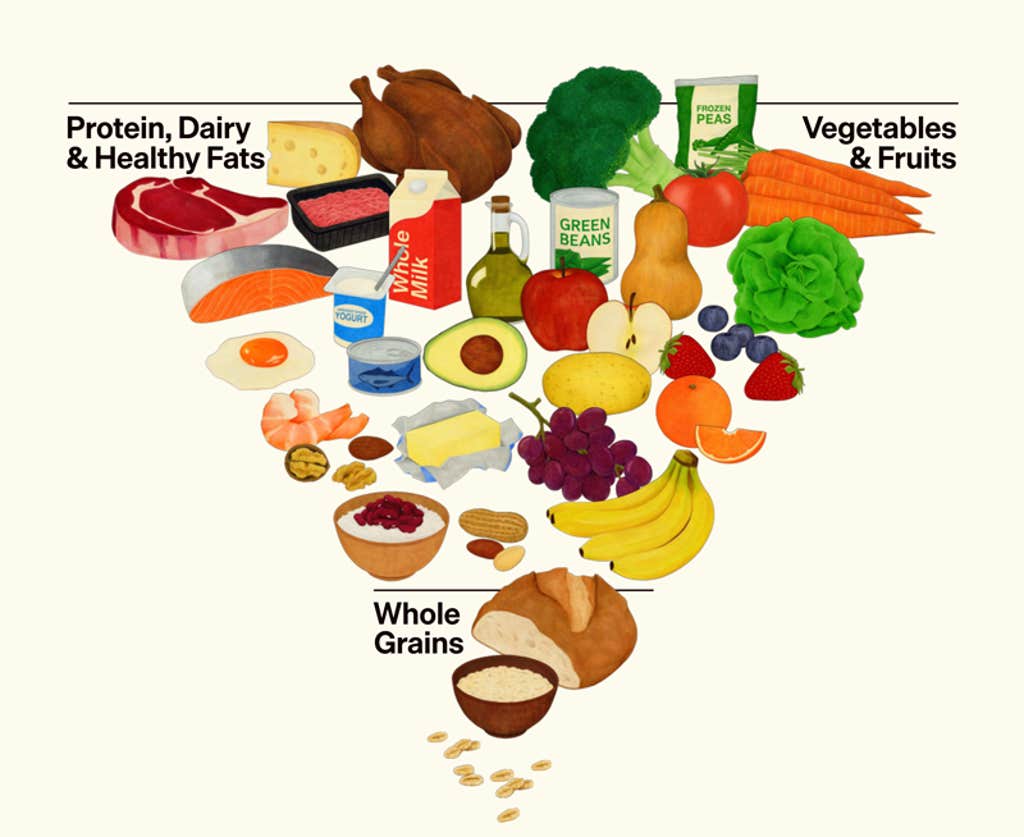

“I find it very disheartening that the new pyramid places red meat and sources of saturated fats at the top, suggesting that these should be prioritized,” remarked Christopher Gardner, a nutrition expert at Stanford University, to NPR. “This contradicts decades of established evidence and research.”

Saturated fats fall into one of two primary categories of fatty acids. Typically, we acquire saturated fats from animal-based products such as cheese, butter, pork, and beef, as well as from oils like coconut and palm oil. In contrast, unsaturated fats are abundant in foods such as fish, avocados, nuts, seeds, and various cooking oils, including olive and soybean oil.

Studies have associated diets high in saturated fats with increased cholesterol levels and a higher risk of coronary heart disease since the 1950s. Among those early researchers was Ancel Keys, a physiologist born on this day in 1904. Early in his career, he developed compact, nutritionally balanced rations for World War II soldiers facing starvation risks, though some soldiers complained about being stuck with these three-meal packages for prolonged periods.

After the war, Keys observed a rise in heart attack cases across America. He suspected this spike was linked to lifestyle and dietary changes from that era, doubting the then-popular idea that plaque buildup in arteries occurred naturally with aging.

Read more: “How the Western Diet Has Derailed Our Evolution”

To explore the connection between diet and heart health, Keys initiated a pilot study in the 1950s. This ambitious project monitored over 11,000 healthy middle-aged men from seven countries, including the U.S., Japan, and Italy, spanning almost 60 years. Dubbed the Seven Countries Study, it was the first comprehensive, multinational investigation into how various risk factors, such as diet and lifestyle, contributed to the development of coronary heart disease. Keys and his team discovered that blood pressure, high cholesterol, diabetes, and smoking were universal risk factors for coronary heart disease.

Keys’ research continues to shape dietary practices globally. For instance, researchers identified that dietary habits in Italy and Greece during the 1950s and ’60s were associated with a lower incidence of coronary heart disease. Known today as the Mediterranean Diet, this lifestyle involves a high intake of olive oil, along with plenty of fruits, vegetables, cereal products, legumes, and moderate consumption of fish, while limiting dairy and meat.

In the years following Keys’ study, further research has corroborated his findings: reducing saturated fat can lower levels of “bad” LDL cholesterol, which is linked to heart attack and stroke risks. This is primarily because excessive saturated fat can hinder the liver’s ability to metabolize LDL cholesterol, leading to its accumulation in the bloodstream and, ultimately, plaque formation in the arteries.

However, recent studies have added complexity to this issue: it remains unclear if all saturated fat sources have the same harmful effects. For instance, low-fat dairy may not be healthier than full-fat alternatives, with some studies linking full-fat dairy to more positive health outcomes. Overall, the findings are varied; researchers speculate that the composition of dairy products, including their vitamin and protein content along with beneficial gut bacteria, might influence how our bodies process these fats.

That said, the core findings of Keys’ research remain relevant, and experts recommend limiting consumption of foods high in added sugars, saturated fats, and sodium. Instead, they advocate for a diet rich in fruits and vegetables, whole grains, healthy protein sources such as fish and legumes, and oils like canola and olive oil—excluding beef tallow.

If you enjoy Nautilus, consider subscribing to our free newsletter.

Lead image: thomasmaiwald / Pixabay