Yves here. Understanding the long-term economic repercussions of severe weather events poses a significant challenge for economists, as these situations differ widely in type, geographical scope, and severity. Nevertheless, such analyses are vital; they may influence the magnitude of future relief efforts and bolster arguments for climate change mitigation, especially under a more progressive administration than the previous one. Notably, improved regional infrastructure has the potential to mitigate the effects of environmental disasters.

This article contributes to an expanding body of research but suggests that focusing solely on localized weather disasters—such as hurricanes, catastrophic floods, and wildfires—limits its scope. While heatwaves are mentioned, the modeling lacks clarity regarding the heightened energy usage, potential grid failures or brownouts, and heat-related fatalities that accompany such events.

By Hélia Costa, Economist, Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD), and John Hooley, Senior Economist, International Monetary Fund. Originally published at VoxEU

Extreme weather events are occurring with increasing frequency and intensity, yet their macroeconomic impacts remain inadequately understood. This column argues that because climate-related natural disasters are highly localized, their repercussions should be evaluated at the subnational level, while also accounting for cross-regional spillovers. This method reveals significant adverse effects, estimated to be around 0.3% of GDP per year in OECD countries, with approximately half of these losses transpiring outside the disaster zone due to negative spillovers.

As severe weather events like catastrophic floods and extended heatwaves become more common (IPCC 2021), policymakers are turning their attention to the economic resilience of both developing and advanced nations ahead of COP30. While there is increasing consensus on the serious macroeconomic consequences of these events (Krebel et al. 2025), accurately quantifying these losses remains challenging (Aerts et al. 2024).

For advanced economies, it has been more difficult to document strong, negative impacts, particularly in studies utilizing cross-country data (Botzen et al. 2019, Klomp and Valckx 2014). Recognizing the localized nature of weather shocks, an increasing number of studies advocate for assessing their impacts at a subnational level (Goujon et al. 2024, Dell et al. 2014), emphasizing the necessity of integrating granular data from various countries and event types to fully capture their macroeconomic consequences.

In this context, our recent research (Costa and Hooley 2025) employs regional data from over 1,600 regions across 31 OECD countries from 2000 to 2018 to evaluate the economic repercussions of extreme weather events in advanced economies, including how effects propagate beyond the original disaster site through spillover effects.

Large, Persistent, and Non-Linear Impacts

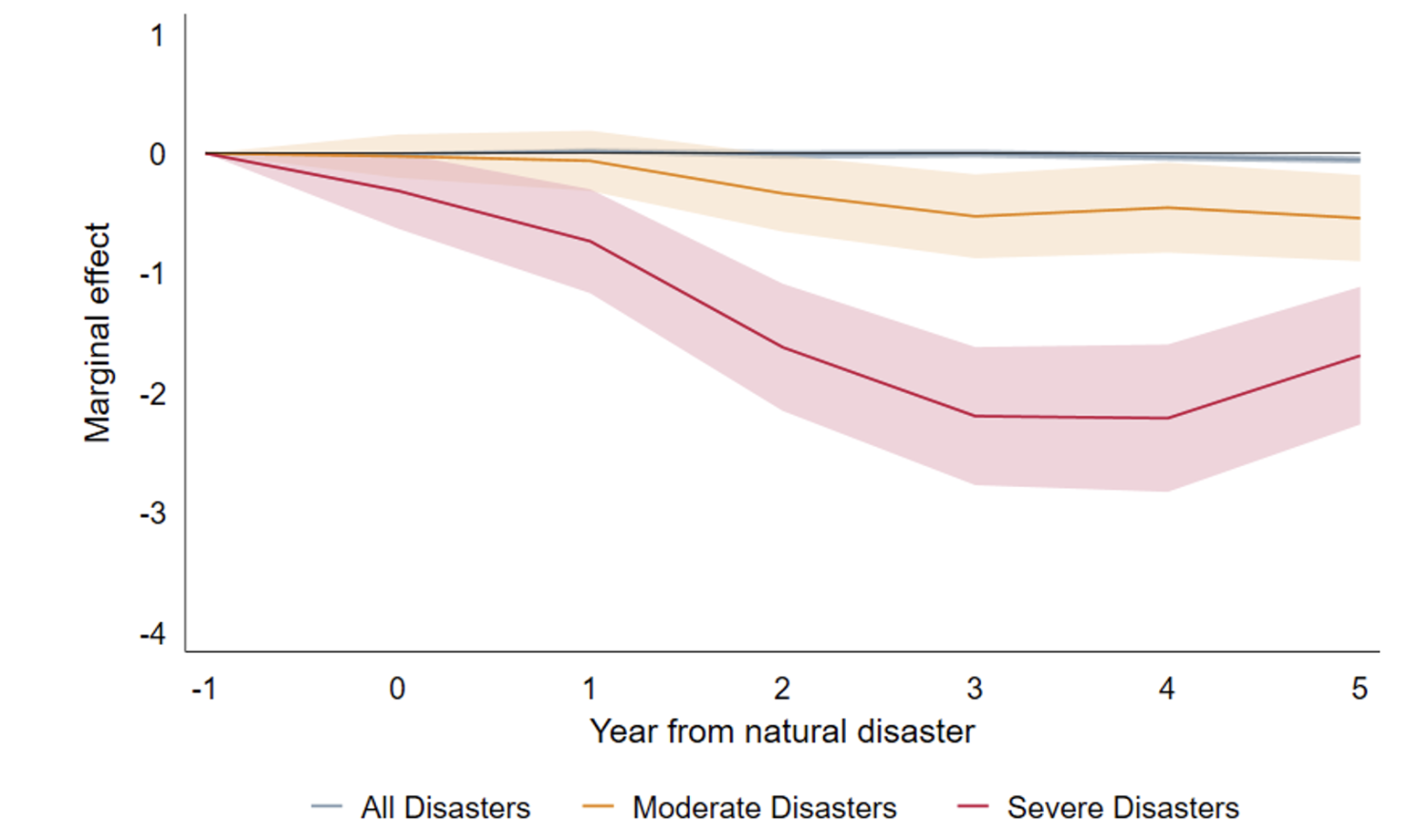

The most severe disasters can reduce GDP in directly affected regions by as much as 2.2% relative to the trend, with losses around 1.7% persisting even five years later (Figure 1). However, not all disasters exert equal influence; the most severe incidents—affecting at least 0.1% of a region’s population—lead to disproportionately larger output losses than more moderate disasters, while minor events show negligible GDP effects. This non-linearity has been noted in previous studies (Felbermayr and Gröschl 2014) and likely stems from capacity constraints—technical and organizational limitations that manifest primarily in major disasters (Hallegatte et al. 2007). Smaller shocks tend to be absorbed, whereas large shocks overwhelm the system.

Figure 1 Change in the level of real GDP following severe disasters (percent)

Note: Lines indicate local projection estimates at each horizon following the disaster for all, moderate, and severe disasters; shaded bands denote 90% confidence intervals.

Source: Costa and Hooley (2025); data: OECD, EM-DAT, GDIS (Rosvold and Buhaug 2021).

Labour markets serve as a crucial adjustment mechanism: employment typically decreases in line with GDP, and affected regions often experience net outward migration. While mobility aids households in coping, it can also exacerbate local output losses by diminishing demand and depleting human capital.

Moreover, severe disasters exert downward pressure on prices, with the GDP deflator dropping to about 1% below trend in the medium term. In these circumstances, demand deficiencies outweigh any supply-side inflationary impacts arising from damaged capital, disrupted production, and labour market turmoil.

These effects represent net outcomes for output and prices, already factoring in offsets like reconstruction spending, insurance payouts, and government relief transfers. The enduring nature of significant losses suggests that while such support is beneficial, it is usually not enough to restore the economy to its pre-disaster trajectory.

Negative Spillovers to Neighbouring Regions

The economic ramifications extend beyond regional borders. Our analysis reveals significant negative spillovers: a severe disaster occurring within 100 km of a region can trigger an additional 0.5% drop in GDP—approximately a quarter of the direct impact. These spillover effects arise from various factors, including supply chain disruptions, reduced demand from nearby affected regions, and population displacement.

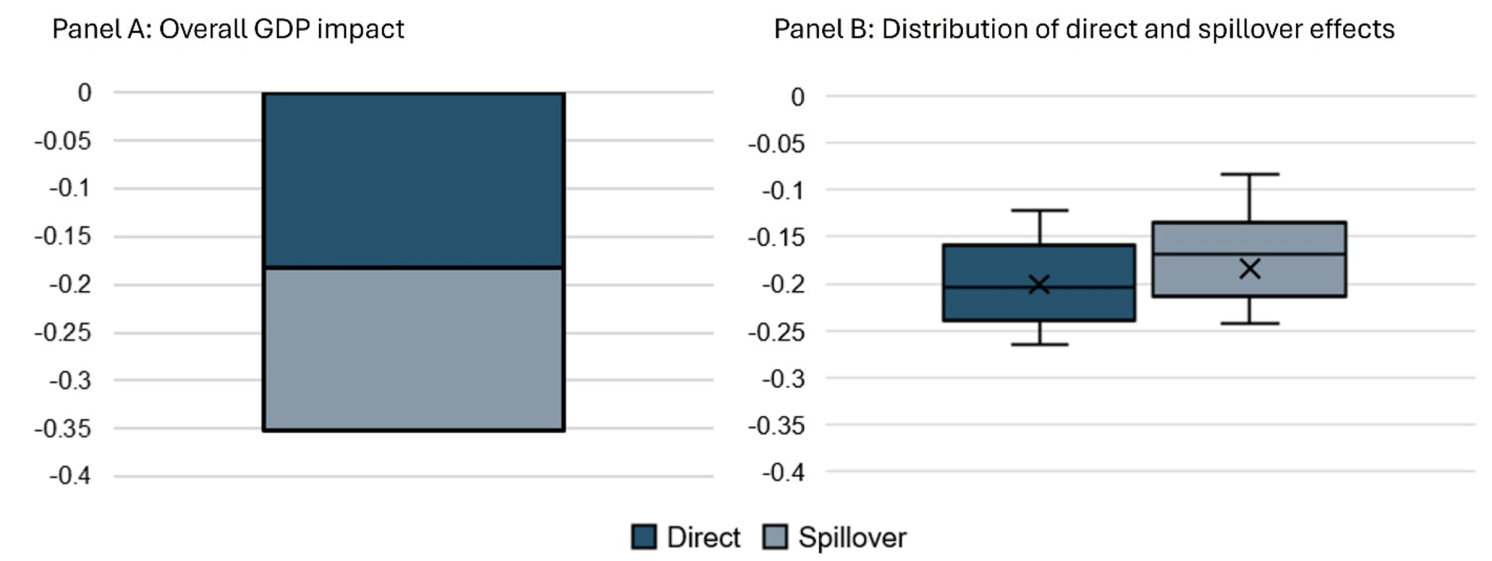

When combining both direct and spillover effects and aggregating across OECD nations, severe disasters within our dataset resulted in an over 0.3% average yearly reduction in GDP, with spillovers accounting for about half of the total loss (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Average annual impact of severe disasters on OECD GDP during 2006-2018 (percent)

Note: Panel A shows the average annual GDP loss across 31 OECD countries (2006–2018) from severe disasters, combining direct effects and spillovers from incidents within 100 km. Losses are calculated by applying estimated elasticities over a five-year horizon and aggregating from region to country. Panel B depicts the distribution of yearly direct and spillover effects. The marker and horizontal line denote the mean and median, while the top and bottom of the box indicate the interquartile range, and the whiskers illustrate the minimum and maximum values.

Source: Costa and Hooley (2025); data: OECD, EM-DAT, GDIS (Rosvold and Buhaug 2021).

Why Some Regions Are More Resilient

The ability of regions to endure and recover from disasters varies widely. Fiscal capacity plays a vital role; regions in countries with lower debt-to-GDP ratios tend to rebound more swiftly, enabling governments to provide effective post-disaster support without implementing austerity measures that could worsen the economic downturn (Canova and Pappa 2021). Furthermore, economic diversification and labour mobility contribute to resilience: diverse economies can shift activities to sectors less affected by disasters, while enhanced mobility facilitates reallocation and mitigates prolonged unemployment (Beyer and Smets 2015).

The effects on different sectors can be starkly different as well. Industrial output typically declines more than twice as much as service output following a severe disaster—reflecting industry’s reliance on fixed capital and interconnected supply chains. However, industry often sees a faster rebound in the medium term as supply chains are reestablished and reconstruction spending increases.

Policy Implications

Quantifying the potential economic impact of natural disasters is essential for effective planning and decision-making. Our findings—including significant, non-linear, and lasting costs even in advanced economies—underscore the need for climate damage projections to account for extreme event impacts. This undertaking is complex, as recent studies have begun to integrate temperature and precipitation volatility into climate damage functions, yet the most extreme ‘tail’ events are likely to remain unaccounted for (Aerts et al. 2024).

The magnitude of these losses further emphasizes the urgency for adaptation initiatives in advanced economies. Investments in adaptive infrastructure—such as flood barriers, water storage solutions, and resilient transport and power systems—should go hand in hand with credible post-disaster plans and more robust insurance markets (OECD 2024).

Our findings regarding negative spillovers carry a vital policy message: climate adaptation strategies should not solely concentrate on areas directly threatened by potential hazards. Since approximately half of the economic damages from natural disasters occur in regions far removed from direct impacts, a narrower focus would leave substantial costs unaddressed.

This leads to several complementary priorities:

- Infrastructure resilience beyond the hazard zone. Given that supply chain interruptions lead to negative economic spillovers, investments in resilient infrastructure must consider these network effects.

- Cross-border coordination mechanisms. Effective disaster response necessitates the establishment of shared early warning systems, integrated disaster response and recovery plans, and possibly coordinated fiscal support.

- Reduce labour market frictions for reallocation. Encouraging flexible labour market policies and targeted upskilling initiatives can facilitate quicker transitions for displaced workers into new employment opportunities in less-affected sectors or regions.

Enhancing resilience to spillover effects—in conjunction with broader adaptation strategies—is critical to mitigating both economic and social repercussions from extreme weather events and preventing disasters from exacerbating regional inequalities.

See original post for references