In this analysis, we delve into the rapid advancements made by China in critical technologies, particularly artificial intelligence (AI), semiconductors, and quantum computing. Given the current state of innovation and competition among global superpowers, understanding these dynamics is essential for strategizing future growth and development in technology. This article reflects on the strengths and weaknesses of key players, including the United States, China, and Europe, to shed light on the implications of these advancements for global competitiveness and cooperation.

By Alicia García-Herrero and Michal Krystyanczuk. García Herrero serves as the Chief Economist for Asia Pacific at the French investment bank Natixis and is also a Board Member of AGEAS insurance group and a Senior Fellow at Bruegel. Her expertise lies in emerging markets, particularly regarding Asia and its relations with the European Union. Krystyanczuk is an experienced Data Scientist focused on harnessing Artificial Intelligence for societal impact, frequently consulting on various AI projects across different sectors, including pharmaceuticals, marketing, and finance. Originally published at Bruegel.

Executive Summary

This Policy Brief explores China’s swift growth in cutting-edge innovation within artificial intelligence, semiconductors, and quantum computing, highlighting the key companies behind these advancements. While the United States maintains a leading position overall, China is closing the gap, particularly in sectors like semiconductor fabrication, AI video and audio processing, and aerial vision. However, China still trails in quantum computing. The European Union significantly lags behind both the US and China regarding groundbreaking patents, showing slightly better performance in quantum technologies.

Innovators in China and the US are notably quicker than their European counterparts in replicating new patents from other nations. It takes European innovators over twice as long to replicate breakthroughs in AI, semiconductors, or quantum technologies compared to their US or Chinese peers. This rapid replication in China—almost at par with the US—indicates an accelerating rate of innovation capabilities in pivotal technologies, even in sectors with stringent export controls.

China also demonstrates a notable variety of companies and institutions leading in patent filings. In the US, innovations are predominantly concentrated among large tech firms. European patents originate from a mix of companies and public research centers, with a notable dominance from the telecommunications sector compared to other regions.

Moreover, China is advancing in indigenous innovation in basic research, particularly in semiconductors, to which considerable resource allocation has been dedicated. In contrast, Europe’s fragmented markets and reliance on public research hamper scalability and commercialization. To bridge the gap, Europe must boost research and development in critical technologies while fostering a more integrated national innovation ecosystem.

1. Introduction

The race for dominance in essential technologies—specifically artificial intelligence, semiconductors, and quantum computing—has become pivotal to economic and strategic strength. These technologies form the foundation of various applications, from autonomous weapons to climate modeling, with their control impacting global supply chains, national security, and economic stability.

China’s rapid progress in these domains has led to a widespread belief that the country might already be rivaling the US, thus fulfilling its long-held ambitions for self-reliance. For example, the exceptional launch of DeepSeek’s cost-effective, open-source AI model in early 2025 significantly outperformed benchmarks set by US leaders such as Meta, even under strict chip export restrictions, reinforcing perceptions of China’s advancing AI capabilities. Conversely, the European Union is perceived as lagging in technological breakthroughs (Draghi, 2024).

This Policy Brief analyzes China’s standing in comparison to the US and EU regarding AI, semiconductors, and quantum computing. By examining these economies’ basic research capabilities and the speed of their replication of global innovations, we aim to assess how quickly technological spillovers can mitigate the lack of breakthroughs for countries not at the forefront of critical technologies.

Ultimately, we will analyze the companies or research institutions contributing most to these breakthroughs and the differences across China, the US, and the EU. This analysis draws on findings from García-Herrero et al. (2025b).

While China shows marked advancement in AI, semiconductors, and quantum computing, significant caveats exist. Understanding how China has rapidly ascended the innovation ladder and the reasons behind Europe’s slower pace will be critical for Europe to develop a more effective strategy in these technologies, helping to bridge the gap with the US and, in certain cases, China.

2. Current Standing of China

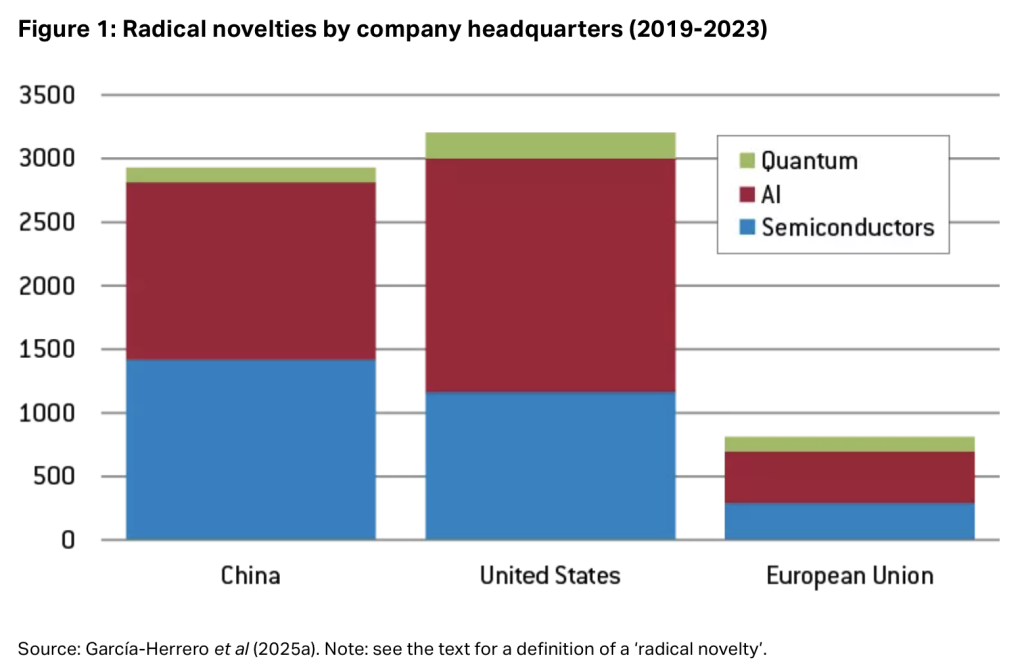

Since 2019, the number of Chinese patent applications in AI, semiconductors, and quantum computing has surged. Yet, as of 2023, China has not yet surpassed the US (Figure 1)2. When considering ‘radical novelties’—defined as new patents without prior similar patents that are repeated at least five times—China sits in second place after the US for both AI and semiconductors. The EU ranks a distant third, except in quantum technologies, where it and China stand nearly equal, although both are significantly behind the US.

China’s advancement is particularly notable in semiconductor-related radical novelties, followed by AI, and, to a lesser extent, quantum (Figure 2). The US clearly leads in quantum technologies and maintains dominance in AI, though China is making notable gains. In semiconductors, China appears to have taken the lead, but this analysis may be missing key contributors from South Korea and Taiwan, which are integrated into the US technology ecosystem.

However, assessing dominance across broad fields such as AI, semiconductors, or quantum computing lacks depth. Figure 3 summarizes a more detailed evaluation of subfields within these critical technologies.

In the realm of AI, China has made substantial progress in computer vision for surveillance and autonomous systems, accounting for over 40 percent of the radical novelties in these sectors among China, the US, and the EU. China’s comparative advantage in these technologies has quickly translated into practical applications, particularly with smart-city infrastructures that manage vast amounts of data daily3. In aerospace AI, Chinese enterprises lead with 55 percent of the breakthroughs in these fields. They have notably pioneered swarm intelligence for logistics, gaining an upper hand over both the US and EU4.

In semiconductors, China’s strength lies in hardware-intensive and production-focused subdomains. In these areas, China claims 65 percent of all novel patents filed by China, the EU, and the US with a key emphasis on 3D stacking for high-density memory (García-Herrero et al., 2025a). This technology is essential for advanced AI applications, suggesting that China could produce AI chips were it not hindered by external constraints, especially in lithography5. Rapid advancements in chip technology have been bolstered by strong government support through initiatives like Made in China 20256. This growth from semiconductor manufacturing to areas such as robotics reflects a strategic effort to internalize previously imported capabilities, leveraging industrial coordination as a technological multiplier.

The field where China still trails is quantum technologies. While the US holds the lead across most quantum subfields, China has made strides in specific areas, such as trapped-ion systems that enhance precision measurements for purposes like earthquake prediction (Omaar and Makaryan, 2024).

Despite notable advancements, the US retains dominance across the board for two primary reasons. First, the US excels in the most sophisticated subfields, including machine learning, chip design, materials science, and quantum systems control. Second, the US’s vertically integrated structure promotes a focus on deepening algorithmic and design specialization, creating foundational breakthroughs in hardware. This interconnectedness aids technology diffusion across disciplines; for instance, advancements in AI algorithms can enhance chip designs, which in turn can improve quantum computing architectures. Although companies may relocate manufacturing overseas, the resulting ecosystem in the US, while less diverse than China’s, is formidable and difficult to replicate due to its control over the critical stages of design, optimization, and data integration, thereby facilitating considerable spillovers throughout the value chain.

Europe continues to excel in various subfields, including robotics, medical AI, power electronics, lithography, and quantum photonics; however, these strengths are more isolated compared to those of the US and China. Opportunities for Europe to catch up exist in complementary niches. In quantum photonics, Europe holds 28 percent of radical novelties, outperforming China. In AI ethics and explainable models, Europe is nearly on par, with an 18 percent share compared to China’s 20 percent, where innovations in bias-mitigation frameworks align well with the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR, Regulation (EU) 2016/679) and provide pathways for exportable standards. In semiconductors, Europe’s 15 percent dominance in lithography may understate a crucial strength, aided by Dutch firm ASML’s near-monopoly on extreme ultraviolet (EUV) tools (VerWey, 2024).

In summary, while both the US and China have their unique advantages, the EU is lagging behind. China’s emphasis on manufacturing-related technologies facilitates rapid scaling, while the US thrives on tight integration between design and application, ensuring swift feedback loops. Europe’s flatter profile demonstrates excellence in individual niches but lacks the connectivity required to compete robustly. Thus, Europe showcases depth but fails to achieve the necessary density or scale.

3. Companies Driving Innovation

Innovation ecosystems vary significantly among China, the US, and the EU (García-Herrero et al, 2025b). Chinese innovators demonstrate a diverse range of company types, while the US is dominated by tech giants and Europe occupies a middle ground with a greater reliance on public research centers.

In the US, a concentrated number of tech companies drive the entire spectrum of radical novelties. Industry leaders like Microsoft, IBM, Intel, and Qualcomm are heavily involved in various critical technologies, and firms such as Micron Technology, Google, and Amazon rank among the top ten US innovators by novel patent counts. This high concentration, although risky, promotes synergies and, backed by the world’s most substantial venture capital markets, hastens commercialization, albeit at the risk of siloing innovation primarily to the digital space.

US companies excel in design and software-driven sectors. Notably, AI firms like Microsoft, Google, IBM, and Nvidia lead significant advancements in machine learning and natural language processing, with Amazon concentrating on applied natural language processing. In semiconductors, US firms are more innovative compared to their Chinese and EU counterparts in chip design, materials, and power electronics, supported by a dense collaborative network involving Intel, Qualcomm, Applied Materials, and Micron.

In the realm of quantum computing, IBM leads in hardware and control systems, combining research efforts with early commercial applications. The interconnections among AI, semiconductors, and quantum technologies facilitate robust cross-sector spillovers, enabling rapid transitions of innovative ideas from laboratories to market. For instance, Google’s Willow quantum chip, developed using advanced semiconductors and AI-driven error correction, facilitates quick qubit scaling for applications in battery and drug simulations, leveraging open-source tools to expedite ideas into practice in minutes.

The significant concentration of tech companies within the US ecosystem underscores its core strength: an integrated approach that merges research, engineering, and commercialization. This synergy transforms advanced science into scalable innovations, particularly in critical technologies where ecosystems bolster one another. For example, advancements in AI algorithms fuel innovations in chip design and vice versa.

However, the concentration of basic research within a few major companies presents challenges. Smaller innovations often get absorbed by these tech giants, potentially hindering new innovation paths and fostering technological dependency. In essence, while the US innovation ecosystem excels, its narrow focus on digital and algorithmic technologies may overlook industrial and hardware applications. To maintain its lead, the US must promote wider participation across industries.

In stark contrast to the US, China boasts a more balanced mix of private and public entities, with the true differentiator being the diverse range of companies across various sectors, fostering a more versatile ecosystem. While Huawei plays a dominant role in AI, semiconductors, and quantum technologies, the involvement of differing companies enhances China’s innovative landscape. Various champions in semiconductors—like TCL Technology, Changxin Memory, Yangtze Memory, and SMIC—coexist with large telecom players such as Huawei. Notably, Ping An, an insurance firm, leads in AI innovations related to predictive health analytics, adapting financial models for nationwide telemedicine applications.

Tech platforms such as Tencent and ByteDance are also innovating in video-processing AI, alongside robotics firms like Autel and UBTECH, which are developing quantum-enhanced sensors for industrial automation. Additionally, consumer goods company Haier makes strides in optimizing cooling solutions for data centers. This diverse range of sectors, more than 15 in total, combined with close ties to academia—such as through Tsinghua University’s hubs—fosters innovation diffusion in sectors including surveillance AI and e-commerce logistics. China’s model encourages all firms with high R&D intensity to innovate, supported by industrial policy programs like ‘Little Giants’ (García-Herrero and Krystyanczuk, 2024).

China’s more varied ecosystem combines industrial policy and market experimentation. Public funding grants strategic direction while private enterprises compete to deliver scalable solutions. This dynamic results in a fast-evolving innovation base that integrates digital technologies with manufacturing in line with national objectives.

Europe relies more on public research centers, particularly in the quantum sector, where organizations such as CEA (France) and universities like RWTH Aachen, Valencia, and Delft lead in generating novelties—accounting for 60 percent of EU quantum radical innovations. However, involvement from private companies is limited in comparison to firms in the US and China, particularly in AI and semiconductors. Nonetheless, some firms, like Ericsson and Nokia, contribute notably in AI for 5G computing, while Infineon captures 42.9 percent of radical innovations in power semiconductor devices (García-Herrero et al., 2025b).

Europe is home to two entities excelling across all three critical fields: Sweden’s Ericsson and France’s CEA. Despite their different natures—one being a private telecommunications company and the other a public research center—both share significant commonalities: higher R&D expenditures than their counterparts and extensive collaboration with research leaders.

Despite these relatively successful examples, the reality is that the number and depth of European breakthroughs in digital technologies remain less competitive than those of China and the US. This challenge is likely linked to the lack of an integrated market for basic research and the fragmentation of the single market, which impedes the profitable commercialization of innovations.

4. Speed of Knowledge Spillovers: Quick for China and the US, Slow in Europe

While competition for radical innovations is significant, the ability to replicate successful ideas is equally important. To evaluate how the US, EU, and China replicate breakthroughs in critical technologies, García-Herrero et al (2025b) conducted a spillover analysis, revealing concerning findings for Europe. In this context, spillovers refer to the dispersal of new technologies or ideas from one region to others, assessed by observing the time lapse between the unveiling of an original, radically novel patent and the emergence of similar technologies in other regions.

Among the critical technologies analyzed, AI demonstrates the fastest spread (Figure 4). China excels by replicating novel patents from the US or EU within merely six months. There is a notable bidirectional flow, as US firms also quickly adopt Chinese patents. In terms of chips, however, China replicates US patents at a rate about half that of its AI replication speed, consistent with the majority of US export controls related to semiconductors11.

Conversely, EU countries typically require 18-24 months to mimic innovations from China or the US, whether in AI, chips, or quantum technologies. Intriguingly, EU innovators tend to replicate Chinese patents slightly more swiftly than US patents, particularly in AI and quantum. The time lag for chips is comparable for both US and Chinese patents.

Europe’s comparatively slow replication of patents from the US or China poses significant concerns. This issue is exacerbated by the sluggish pace of innovation within Europe itself. In practical terms, the duration for a breakthrough in one EU nation to be replicated by an investigator from another EU nation matches, if not exceeds, the time taken by a European innovator to replicate a Chinese patent (with replication of US breakthroughs remaining the slowest).

Such insights are striking yet troubling, warranting further examination of the factors invoking this discrepancy. Our investigation into the fragmentation of research excellence in Europe, combined with the differing profiles of its innovators relative to those in the US and China, reveals several contributing factors:

- Dependence on public funding in the EU versus the robust venture capital markets that underpin funding for critical technologies in the US.

- The absence of sufficiently capitalized tech firms within the EU, limiting their ability to undertake bold innovative ventures and replicative efforts.

- Language barriers and regulatory complexities in the EU, along with potentially excessive data protection measures.

- Fragmentation within the single market and the ensuing scalability issues during the commercialization of innovations (Draghi, 2024).

5. Implications and Recommendations

While the US remains a frontrunner in the development of radical innovations across AI, semiconductors, and quantum computing—augmented by a concentrated ecosystem of private tech giants excelling in high-value subfields—the model fosters rapid commercialization. This ecosystem produces 35 percent to 40 percent of radical innovations across China, the EU, and the US, translating theoretical advancements into trillion-dollar industries.

China has emerged as a formidable contender, particularly in semiconductor fabrication and specific AI applications, such as surveillance technology and drone swarm logistics. Its hybrid model and state-backed scaling allow for quick absorption and adaptation of innovations. In contrast, despite Europe’s strength in quantum photonics and explainable AI, it lags in generating novel ideas compared to China and the US, struggling with sluggish spillover rates that limit its competitiveness. While Europe dominates in select niches, such as ASML’s EUV monopoly, the fragmentation of its innovation landscape presents a notable drawback.

This gap may widen if the EU does not urgently enhance its innovation efforts in critical technologies and establish conducive ecosystems for more rapid replication of breakthroughs. Increasing the number of innovators is crucial. One vital aspect of China’s swift ascendancy over the US, in contrast to Europe, is its funding approach. Paradoxically, in terms of basic research investment, the EU surpasses China—spending $47.5 billion in 2024 against China’s $34.7 billion (OECD, 2025). However, China’s growth in research expenditure is double that of the EU (over 10 percent compared to 5 percent), illustrating that convergence is occurring rapidly.

In addition, China’s industrial policy efforts have intensified, particularly regarding critical technologies, most notably semiconductors. The push for domestic chip production began with the 2015 initiative, Made in China 2025, and has been supported by substantial funding from two major efforts, the Big Fund I and Big Fund II, totaling around $90 billion (García-Herrero and Weil, 2022). The outcomes of this endeavor are just beginning to bear fruit, as China climbs the ranks, especially in chip fabrication, although challenges in design persist. China’s vast economies of scale also facilitate the commercialization of basic research, supported by a substantial single market and a formidable export machine.

While industrial policy plays a significant role in China’s innovation narrative, it is essential to avoid simplistic conclusions attributing China’s success solely to generous subsidies. Instead, China’s industrial strategy aligns long-term goals outlined in Five-Year Plans with flexible implementation mechanisms, including selectively designating specialized firms through programs like ‘Little Giants.’ This targets R&D intensity and sector concentration, effectively channeling resources into critical technologies, including those scrutinized here. Furthermore, tax deductions on R&D underscore China’s capabilities to excel in specific domains.

The EU cannot directly replicate China’s industrial strategy due to pronounced institutional differences, but it must endeavor to innovate more effectively. A crucial lesson from China’s ascent is that in a world where scale and speed dictate technological dominance, fragmented excellence spells obsolescence. The dynamic character of the US’s private sector and China’s state-driven agility sharply contrasts with Europe’s regulatory caution. Without reform, the EU risks further losing ground to both the US and China. By observing China’s rapid rise—particularly its strategic use of subsidies, spillover efficiency, and cross-sectoral dynamism—the EU can overhaul its innovation policies. It serves the EU to concentrate significantly more on market scale, not just for products and services but for innovation as well.

To enhance basic research and expedite diffusion, Europe should implement a multifaceted strategy that integrates its single market and strengthens commercialization ties. This approach requires not just funding but also institutional redesign, selectively adopting elements from China’s industrial playbook while adhering to EU values of openness and sustainability. Specifically:

- Establish EU-wide sandboxes for patent licensing and technology transfer. Dedicated regulatory spaces would facilitate cross-border research collaboration and counter existing bureaucratic obstacles that exacerbate Europe’s slow replication times.

- Research funding through Horizon Europe may need to focus more rigorously on critical technologies, providing direct financial incentives for private firms to prototype and commercialize innovations, similar to the incentives fueling China’s semiconductor ecosystem.

- Leveraging public procurement as a mechanism for demand generation is crucial. By mandating the inclusion of critical technologies in public contracts—ranging from AI in public services to quantum-secure communications—the EU could create immediate markets that pull innovations from laboratories into practice, fostering the beneficial cycle of diffusion and reinvestment that sustains China’s current advantage over the EU. The EU’s €2 trillion public procurement market could be reinforced through a ‘critical tech mandate’ that requires 30 percent of contracts (e.g., defense, transport) to incorporate EU-sourced AI or semiconductor components by 2028, with non-compliance penalties.

- Creating an EU Critical Tech Observatory, under the European Commission, could facilitate real-time monitoring of global patent trends, allowing proactive “fast-follower” strategies for identifying high-potential innovations.

- Lastly, the EU’s focus on increasing but also better-integrated military expenditures should generate demand for dual-use technologies.

References

Draghi, M. (2024) The Future of European Competitiveness, available at https://commission.europa.eu/topics/strengthening-european-competitiveness/eu-competitiveness-lookingahead_en

García-Herrero, A. & M. Krystyanczuk (2024) ‘How Does China Conduct Industrial Policy: Analyzing Words Versus Deeds’, Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade 24: 10, available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s10842-024-00413-w

García-Herrero, A., M. Krystyanczuk & R. Schindowski (2025a) ‘Radical novelties in critical technologies and spillovers: how do China, the US and the EU fare?’ Working Paper 07/2025, Bruegel, available at https://www.bruegel.org/working-paper/radical-novelties-critical-technologies-and-spillovers-how-do-china-us-and-eu-fare

García-Herrero, A., M. Krystyanczuk & R. Schindowski (2025b) ‘Which companies are ahead in frontier innovation on critical technologies? Comparing China, the European Union and the United States’, Working Paper 08/2025, Bruegel, available at https://www.bruegel.org/working-paper/which-companies-are-ahead-frontier-innovation-critical-technologies-comparing-china

García-Herrero, A. & P. Weil (2022) ‘Lessons for Europe from China’s quest for semiconductor self-reliance’, Policy Contribution 20/2022, Bruegel, available at https://www.bruegel.org/sites/default/files/private/2022-11/PC%2020%202022.pdf

OECD (2025) ‘Main Science and Technology Indicators’, Dataset, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, available at https://www.oecd.org/en/data/datasets/main-science-and-technology-indicators.html

Omaar, H. & M. Makaryan (2024) How Innovative Is China in Quantum? Information Technology & Innovation Foundation, available at https://www2.itif.org/2024-chinese-quantum-innovation.pdf

VerWey, J. (2024) ‘Tracing the Emergence of Extreme Ultraviolet Lithography’, Analysis, Center for Security and Emerging Technology, available at https://cset.georgetown.edu/publication/tracing-the-emergence-of-extreme-ultraviolet-lithography/