Hello, this is Yves. I hope this post sheds light on the dangers of PM2.5 pollution and proves to be useful for some readers. One of my main motivations for residing in a coastal city known for its less glamorous reputation compared to Bangkok is the air quality. For over nine months each year, the prevailing sea breezes keep PM2.5 levels low. The few times when this isn’t the case usually coincide with a heatwave, making it necessary to keep the windows shut and use an air filter—not too much of a burden in those conditions.

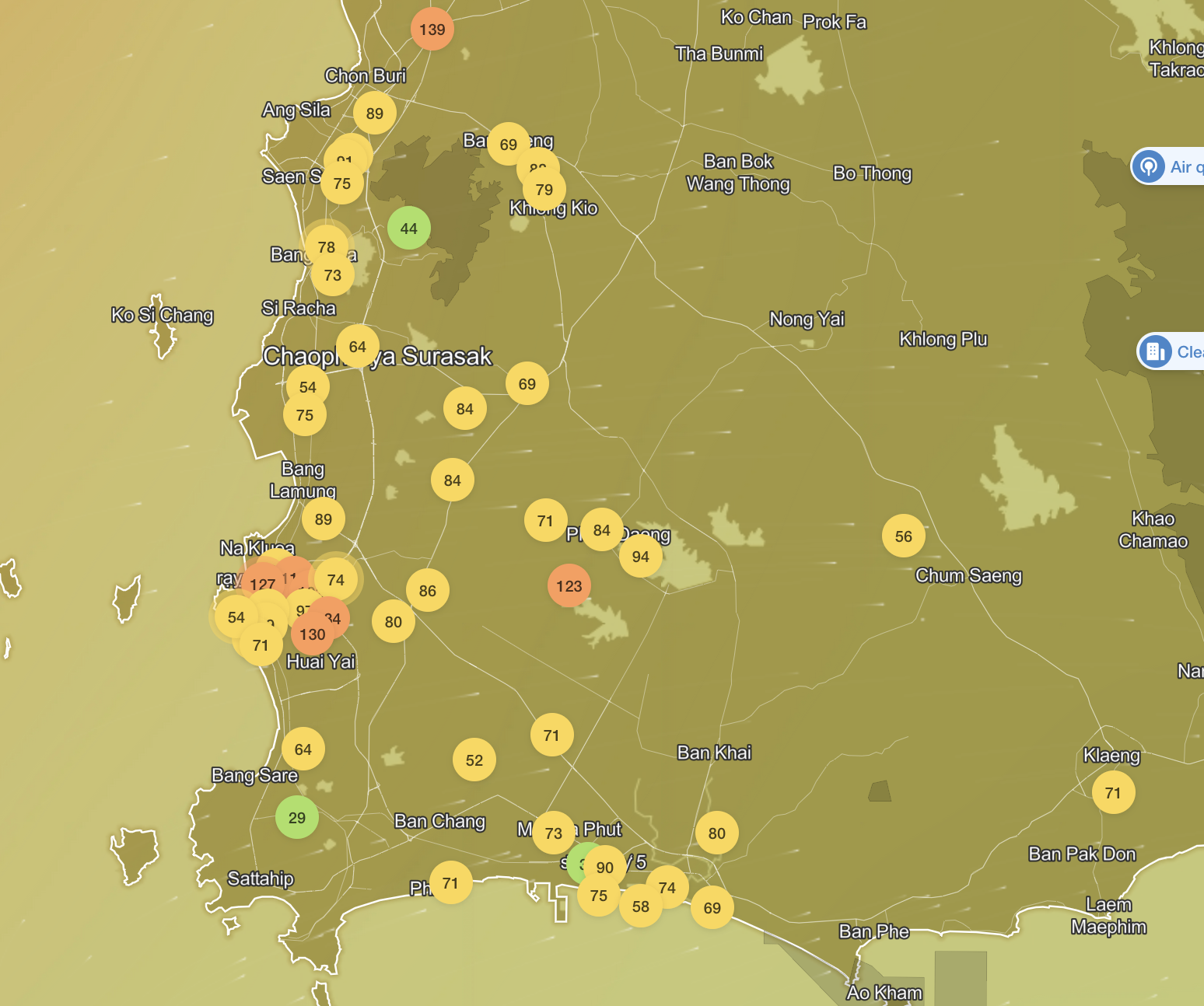

IQ Air offers air quality maps that are updated hourly, even for less prominent cities. This can give you a sense of what the air quality is like in your area without the need to purchase a PM2.5 monitor. For instance, my locality is experiencing worse air quality today compared to a week ago when most monitoring stations reported green conditions. This is typical for high season, marked by increased traffic and crop burning activities.

You can zoom in for a more detailed view as well. The small arrows show that the wind is indeed blowing from the sea. One of the monitoring stations is nearby, so these maps serve as a good approximation for local conditions:

Interestingly, PM2.5 levels can actually rise with elevation in urban settings, meaning being on an upper floor doesn’t necessarily provide an advantage.

Now, on to the crux of the matter.

By Paula Span. Originally published at KFF Health News

For years, two patients visited the Penn Memory Center at the University of Pennsylvania, where medical professionals track individuals with cognitive impairment as they age, alongside a group with normal cognition. Both had consented to donate their brains for research posthumously. “It’s an incredible contribution,” commented Edward Lee, the neuropathologist overseeing the brain bank at the university’s Perelman School of Medicine. “They were both committed to helping us unravel the complexities of Alzheimer’s disease.”

The first patient, an 83-year-old man with dementia, resided in the Center City area of Philadelphia under the care of hired aides. His autopsy revealed significant quantities of amyloid plaques and tau tangles, proteins associated with Alzheimer’s disease, spread throughout his brain. Researchers also identified infarcts, indicating he had experienced multiple strokes.

In contrast, the second patient, an 84-year-old woman who succumbed to brain cancer, exhibited almost no Alzheimer’s-related pathology. According to Lee, “We tested her consistently over the years, and she faced no cognitive issues at all.”

The man lived just a few blocks from Interstate 676, which runs through downtown Philadelphia, while the woman resided a few miles away in the suburb of Gladwyne, surrounded by nature and a country club.

Notably, her exposure to air pollution, specifically the fine particulate matter known as PM2.5, was less than half that of his. Was it merely coincidental that he developed severe Alzheimer’s while she maintained cognitive normalcy?

With mounting evidence linking chronic PM2.5 exposure, a neurotoxin, not only to lung and heart damage but also to dementia, chances are, it is not.

“The quality of your environment directly influences your cognition,” stated Lee, a senior author of a recent study in JAMA Neurology, among several extensive studies released recently showcasing the connection between PM2.5 and dementia.

Researchers have been exploring this connection for over a decade. In 2020, the influential Lancet Commission recognized air pollution as a modifiable risk factor for dementia, akin to common issues like hearing impairment, diabetes, smoking, and hypertension.

Yet, these findings coincide with a time when the federal government is backing away from initiatives aimed at reducing air pollution by transitioning from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources.

“The ‘Drill, baby, drill’ mentality is fundamentally misguided,” expressed John Balmes, a spokesman for the American Lung Association, who studies the repercussions of air pollution on health at the University of California-San Francisco.

“Such policies are bound to diminish air quality and lead to a rise in mortality and illness, including dementia,” Balmes said, referring to recent environmental decisions made by the current administration.

Several factors contribute to dementia, of course, but the implications of particulates—tiny solids or droplets in the air—are receiving more scrutiny.

Particulates originate from various sources, such as emissions from power plants, home heating, industrial processes, vehicle exhaust, and, increasingly, smoke from wildfires.

Among different particulate sizes, PM2.5 “is found to be the most detrimental to human health,” per Lee, due to its small size. These particles are easily inhaled, allowing them to enter the bloodstream and circulate throughout the body; they can even travel directly from the nasal passages to the brain.

The University of Pennsylvania led the largest autopsy study conducted on individuals with dementia, incorporating over 600 donated brains collected over 20 years.

Prior research on pollution and dementia primarily utilized epidemiological studies to establish a correlation. Now, “we’re connecting what we observe in the brain to pollutant exposure,” stated Lee, indicating a deeper analytical approach.

The study participants had undergone extensive cognitive assessments at Penn Memory. Leveraging an environmental database, the researchers calculated their PM2.5 exposure based on their home addresses.

Additionally, the scientists developed a matrix to assess the extent of Alzheimer’s and other dementias affecting the brains of the donors.

Lee’s team concluded that “higher exposure to PM2.5 correlates with greater Alzheimer’s disease severity.” The likelihood of more pronounced Alzheimer’s pathology found during autopsy was approximately 20% higher among donors residing in areas with elevated PM2.5 levels.

Another research team recently identified a correlation between PM2.5 exposure and Lewy body dementia, which is associated with Parkinson’s disease. This type of dementia is generally considered the second most prevalent, comprising an estimated 5% to 15% of all dementia cases.

In what is believed to be the largest epidemiological investigation to date concerning pollution and dementia, researchers examined records of over 56 million traditional Medicare beneficiaries from 2000 to 2014. They compared initial hospitalizations for neurodegenerative diseases with PM2.5 exposure based on ZIP codes.

“Chronic PM2.5 exposure was tied to hospitalization for Lewy body dementia,” explained Xiao Wu, a study author and biostatistician from Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health.

After adjusting for socioeconomic and other variables, the researchers determined that the hospitalization rate for Lewy body dementia was 12% higher in U.S. counties with the highest PM2.5 concentrations compared to those with the lowest.

To further validate their findings, researchers administered PM2.5 through the nasal route to laboratory mice, who exhibited “clear dementia-like deficits” after 10 months, said senior author Xiaobo Mao, a neuroscientist at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

The mice struggled with mazes they had previously navigated with ease. They had constructed nests swiftly and efficiently; now, their efforts were haphazard and chaotic. Autopsies revealed that their brains had shrunk and contained buildups of alpha-synuclein, a protein associated with Lewy bodies found in human brains.

A third analysis, published this summer in The Lancet, encompassed 32 studies conducted across Europe, North America, Asia, and Australia. This study similarly discovered “a significant association between dementia diagnoses and long-term exposure to PM2.5,” as well as other pollutants.

Whether so-called ambient air pollution—outdoor pollution—contributes to dementia through inflammation or other physiological mechanisms requires further research.

Although air pollution levels in the United States have decreased over the past two decades, experts are advocating for even stronger policies to promote cleaner air. “Some argue that improving air quality is an expensive endeavor,” Lee noted. “Yet, the costs of dementia care are also substantial.”

Meanwhile, President Donald Trump has promised to enhance the extraction and utilization of fossil fuels while obstructing the transition to renewable energy. His administration has eliminated tax incentives for solar energy systems and electric vehicles, Balmes noted, adding that they are “promoting ongoing coal usage for electricity generation.”

Additionally, the administration has suspended the approval of new offshore wind farms, announced oil and gas drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in Alaska, and is attempting to revoke California’s plans to transition to electric vehicles by 2035 (which the state is contesting in court).

“If policies move in the opposite direction—resulting in increased air pollution—it poses a significant health risk for older adults,” asserted Wu.

Last year, during the Biden administration, the Environmental Protection Agency established stricter annual standards for PM2.5, acknowledging that “the current standards may not adequately safeguard public health and welfare, as mandated by the Clean Air Act.”

In March, the EPA’s new chair announced that the agency would be “re-evaluating” those stringent standards.