Rewrite the following article into original, high-quality English.

Requirements:

– Preserve HTML structure (headings, lists, paragraphs)

– Keep all images exactly where they are

– Improve readability and flow

– Add a short introduction and a short conclusion

– Do NOT mention rewriting or AI

Article content:

As sun-drenched afternoon beer-garden sessions morph into street-lit evening commutes, a reliable winter coat is the item topping most men’s cold-weather wish lists.

Admittedly, it can be a pricey purchase. However, like a pair of well-made shoes or a tailored suit, it’s one of the most important you can make. And provided you buy smart, it’ll last you for many years to come.

But getting it right means knowing your peacoats from your parkas. So, with that in mind, take a look at Ape’s carefully-curated edit of every winter coat style worth considering this season.

Heavy Parka Coat

Arguably the ultimate winter coat, a good parka will keep you warm in even the iciest of temperatures. This style has been favoured by the likes of Antarctic explorers, mountaineers and those who call the coldest places on earth home.

For the sake of argument, we’re going to assume that you fall into none of these categories, but it’s still nice to know your outerwear could stand up to the challenge if you were to get lost on the way to the office and somehow end up on the north face of K2.

Buying Considerations

- Woolrich Arctic Parka in Ramar Cloth with Detachable Fur Trim

- A Day’s March Nikko Puffer Parka

- Canada Goose Langford Parka

- Arket Upcycled Down Expedition Jacket

Originally crafted from caribou or seal skin, today’s parkas will more likely combine a hard-wearing, water-repellent and windproof polyester outer shell with a softer nylon lining. A good parka should be filled with high-quality duck down (responsibly sourced) to provide warmth – aim for a fill power in the high hundreds.

A coyote fur (faux or responsibly sourced) hood will keep biting winds away from the face while maintaining vision, and won’t freeze in sub-zero temperatures. Similarly, drawstrings at the waist and cuffs are not only great for bringing shape to your silhouette but will keep the cold out and the warmth in.

Peacoat

Dressing to be both warm and smart is one of the biggest challenges winter presents. But with a traditional peacoat hanging up in your wardrobe you need never worry about it again. This cold-weather essential is yet another example of the military’s influence over menswear; the style was originally created for Navy officers out at sea.

However, in recent years the world has discovered it lends itself very nicely to pairing with tailoring, or selvedge denim and minimalist trainers. And therein lies the peacoat’s beauty: as well as being warm, it’s versatile and easy to dress up or down. Looking good in the cold has never been so simple.

Buying Considerations

- Private White V.C. Peacoat

- Corneliani Blue Super Fine Wool Beaver Peacoat

- Reiss Present Wool-Blend Double-Breasted Pea Coat

- Suitsupply Navy Peacoat Pure Wool

A classic peacoat will be cropped in length, feature broad lapels reaching almost across the shoulder, be double-breasted at the front, fastened by large buttons, and to the sides house vertical or diagonal-slash pockets. You may even find some iterations with epaulettes, but this is perhaps a step too far.

Your peacoat should be made from durable heavyweight wool, and it always looks best in navy blue.

Chore Coat

The chore coat was built to shield manual workers from the elements, using materials and construction techniques capable of withstanding serious punishment. Today, you’re more likely to see one being sported by an East London barista than a weather-beaten railroad worker but its effectiveness as a winter coat remains the same.

This rugged style works best as part of a casual, workwear-inspired ensemble. But that’s not to say that smarter clothing is off-limits. Try using your chore coat as a substitute for your blazer, combined with a pair of wool trousers, black leather Chelsea boots and a textured shirt for a contemporary take on business casual.

Buying Considerations

- SIRPLUS Navy Cotton Chore Jacket

- Dickies Lined Canvas Chore Jacket

- Carhartt WIP Michigan Corduroy-Trimmed Organic Cotton-Canvas Chore Jacket

- Drake’s Ecru Cotton Duck Canvas Five-Pocket Chore Jacket

A chore coat will often be crafted in a thick material, such as a 12oz, 100% cotton canvas. Being all about utility and function, demand four large front pockets – two at the breast and two toward the bottom of the jacket.

Likely boxy and oversized, to enable layering, a good chore coat will also be water repellent and feature a large collar to turn up when the biting winds snap at your neck. For winter, ensure yours is fleece-lined or similar to deliver extra warmth (you’ll find unlined versions for summer wear).

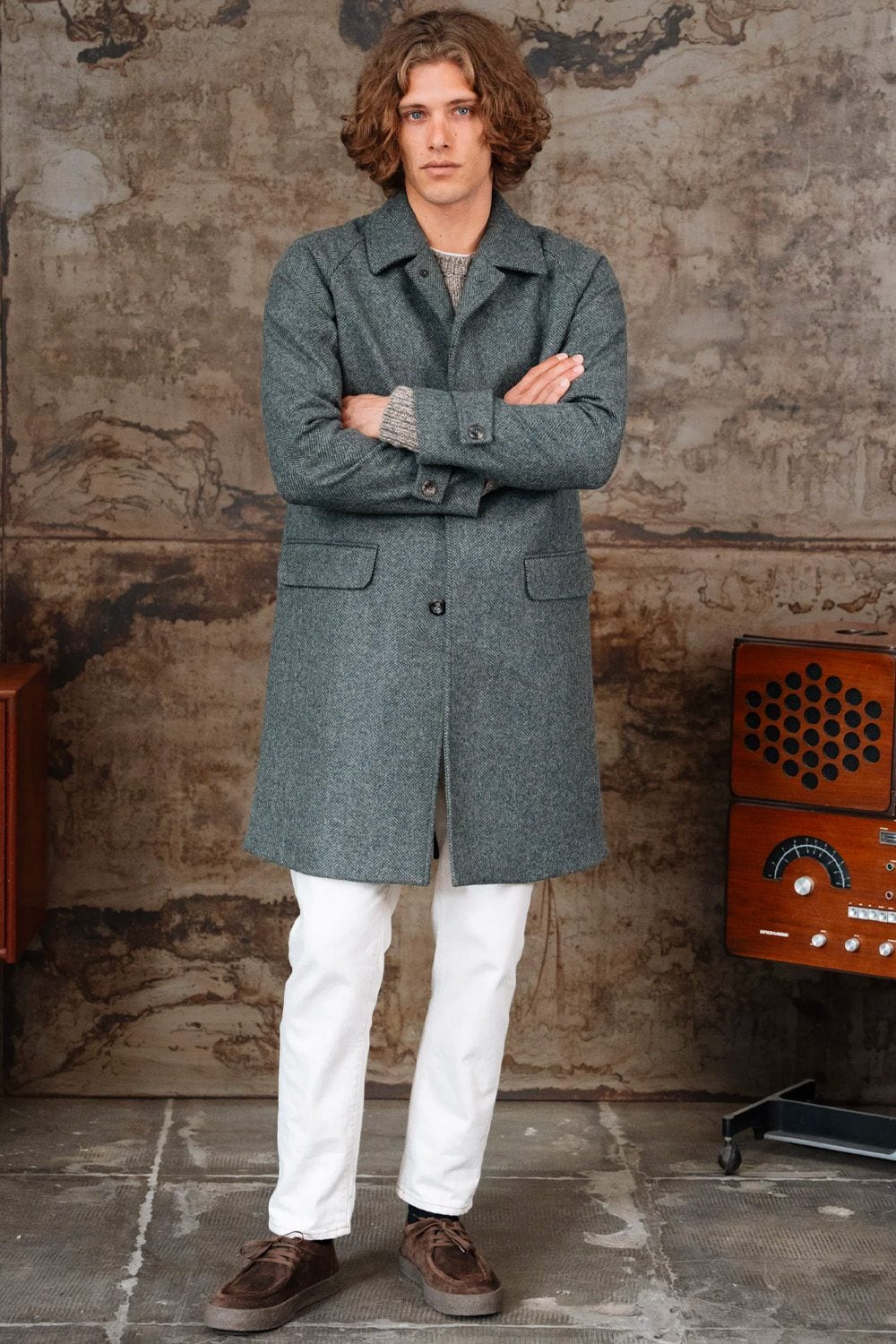

Overcoat

There are few things less enjoyable than enduring a soaking on the way to the office and having to spend the rest of the day in a sodden suit. Finding a suitable top layer that effectively pairs with tailoring can present a challenge but the overcoat provides a foolproof solution.

Wool is naturally insulating and water repellant, plus the extra length in the body keeps the wearer fully sheltered from the elements, trousers and all. Not to mention it looks very sleek too. If cost per wear is a concern, fear not, because this timeless classic looks just as good with jeans, a roll neck and trainers.

Buying Considerations

- Asket The Wool Coat

- Corneliani Navy Blue Super Fine Wool Beaver Coat

- Wax London Stan – Black Wool-Twill Car Coat

- Velasca Bondone

A traditional overcoat finishes below the knee and is double-breasted. However, single-breasted styles are now much more commonplace and equally acceptable, particularly for those who don’t need to add any extra bulk or width to their frame. Go for classic notch lapels, and avoid using the pockets (of which there should be one breast and two waist-height) where possible to maintain a streamlined silhouette. Finally, a three-button fastening brings the coat to a close – button up all three.

Raincoat

When the heavens really decide to open, it’s essential to have something 100% waterproof you can throw on over your clothes. Enter: the raincoat. From minimalist, rubberised versions to smarter macs, a good raincoat is a bonafide menswear essential, particularly for those living in the UK. Most other winter coats keep the weather at bay, but a raincoat will stop it dead in its tracks.

Due to its relaxed yet streamlined appearance, the raincoat is an extremely versatile piece of kit that can be thrown on over everything from your suit during the 9-5 to a sweatshirt and joggers at the weekend. A true all-rounder.

Buying Considerations

- ASKET The Car Coat

- ISTO Trench Coat

- Velasca Volpedo Raincoat

- Corneliani Blue Technical Fabric Trench Coat

Your raincoat should be 100% waterproof and knee-length to keep the top half of your trousers protected. If you really want to remain dry, though, don’t neglect the finer details: taped seams and a waterproof zipper will ensure no water is able to seep through your top layer.

Look for designs made from breathable fabrics such as Gore-Tex, Tyvek or coated nylon – all allow air to pass through, which is vital for releasing bodily vapour, otherwise you run the risk of boiling from within the confines of your binbag-like container on the morning commute.

Puffer/Down Jacket

During those hazy summer months, it can be easy to forget just how bitterly cold winter can be. Still, if you equip yourself with a puffer jacket before the calendar flips over to December, you need never been reminded.

This wearable sleeping bag is the warmest of winter coats, offering unparalleled insulation against the elements. It’s so warm, in fact, that most days you’ll be able to simply throw it on over a shirt or T-shirt. But equally, it’s easy to layer on particularly frosty mornings. Try wearing one with jeans, boots and some chunky knitwear for best results.

Buying Considerations

- Rains Alta Puffer Jacket

- Velasca Sauris

- Uniqlo Seamless Down Parka

- Reiss Reggie Quilted Zip-Through Puffer Jacket

A down jacket should be lightweight (filled with high-quality down insulation) and finish at the waist, allowing better mobility.

A hood with elasticated ties or press studs will keep your head protected from wind and rain, while a zipped front, taped seams and adjustable cuffs ensure that the warmth stays trapped against your body. Insulated pockets (preferably lined in a soft, cosy fabric such as fleece) at the waist are another welcome, yet often overlooked, addition.

Waxed-Cotton Jacket

Times have changed. Today, you don’t need to be a Northumbrian cattle farmer to enjoy the benefits of a waxed-cotton jacket. The rural staple has made its way out of the countryside and into the city, thanks to its timeless styling, good looks and its knack for keeping the wet weather out.

This country classic is one of those rare items that gets better with age. Although you’ll want to make sure to get it re-waxed every few years to keep its water repellency up to scratch.

Buying Considerations

- Private White VC The Permanent Style Wax Walker

- Peregrine Bexley Jacket

- Belstaff Trialmaster Jacket

- Barbour Ashby Waxed Jacket

The ideal waxed jacket finishes just below the hips, offering protection to your seat without sacrificing manoeuvrability. Key details to keep an eye out for include a storm fly front and Velcro wind cuffs to seal out draughts; a corduroy collar that can be flipped up to protect against wind chill; hip pockets lined in fleece or moleskin to keep hands warm; a breathable cotton lining (extra marks if it comes in a heritage print such as tartan) for comfort; plus stud fasteners on the collar to allow for an optional hood.

Due to its country origins, this jacket will always look best in earthy green and brown colourways.

Technical Jacket

At the other end of the spectrum to the waxed-cotton jacket we have the latest teched-out rainwear from the biggest and best names in outdoors apparel. With cutting-edge fabrics and boundary-pushing construction techniques, a technical waterproof may not be the perfect match for your tailoring but it will keep you dry, ventilated and comfortable better than anything else on this list.

If you’re more interested in scaling mountains than attending boardroom meetings then this could well be the style of winter coat for you.

Buying Considerations

- Arc’teryx Beta SL Gore-Tex Jacket

- Sealskinz Brancaster Waterproof Lightweight Rain Jacket

- Haglöfs ROC Flash Gore-Tex Jacket

- Patagonia Torrentshell 3L Rain Jacket

A good technical jacket will, these days, be a carefully orchestrated mix of outerwear built for the serious hiker or climber but suitably styled for wear in the city. Look for a design crafted from a breathable, wind- and waterproof fabric, preferably with a bit of stretch for increased comfort and mobility.

You should also benefit from protective high neck openings, a plethora of pockets, intelligently located zips or fasteners, and athletic, form-fitting cuts.

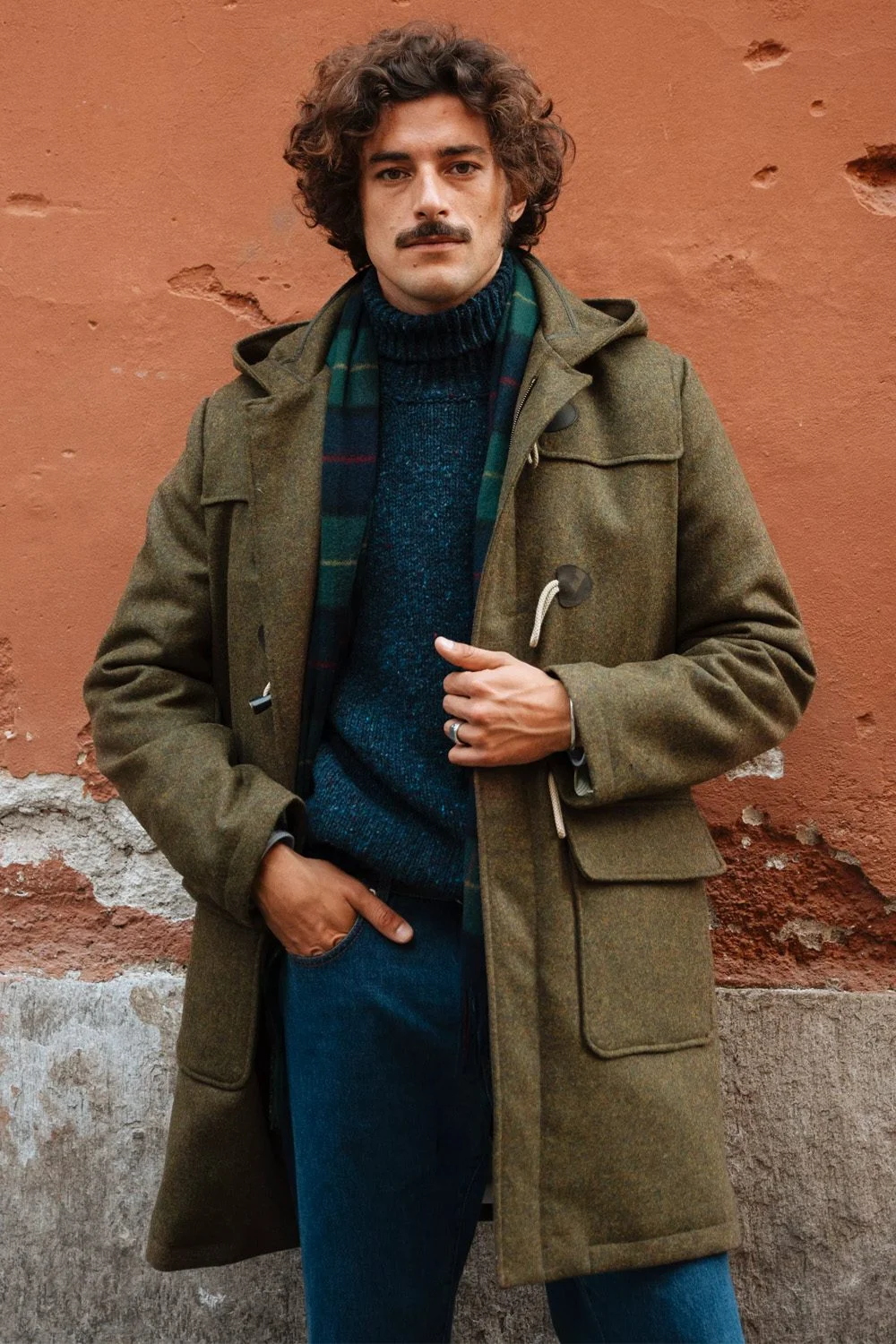

Duffle Coat

Perhaps the king of smart casual outerwear, the duffle coat blends all the best parts of tailored silhouettes like the overcoat and mac with a hearty dose of casual styling. Wool construction keeps the cold out and the warm in, while details such as an oversized hood and wooden toggle fastenings dial the formality down a notch, ensuring it remains weekend-appropriate.

For outfit inspiration, try layering over an Oxford shirt and crew-neck jumper, and styling with dark denim and desert boots.

Buying Considerations

- Gloverall Morris Duffle Coat Camel Buchanan Regular price

- Velasca Castelponzone Duffle Coat

- Mackintosh Kilmarnock Duffel Coat

- Maison Margiela Wool Duffle Coat

The best duffle coats are knee-length and made from heavyweight, double-faced wool for durability and protection. The toggle fastening should run the full length of the coat for optimal protection, with horn toggles and leather loop fastenings adding an understated sense of luxury to what is traditionally a rugged, military silhouette.

Deep, waist-height pockets, a button-adjusted hood and a fixed shoulder cape are the type of practical additions you should be on the lookout for, while tartan linings and subtle branding tags will help separate yours from the crowd.

Shearling Coat

As far as unlikely style icons go, Del Boy is fairly high up the list. Yet worn right (i.e. without a flat cap and sovereign rings) his signature shearling coat can actually be a valuable asset to your cold-weather clothing arsenal.

Be warned, though, if you’re an animal lover this one may not be for you. But thankfully synthetic alternatives are getting so good these days that it’s possible to replicate the look and feel of the real thing without compromising your ethics.

Buying Considerations

- Velasca Balsorano

- Reiss Hardy Shearling-Collar Leather Jacket

- Wax London Kendal – Dark Brown Lamb Leather Flight Jacket

- MR P. Shearling Coat

A traditional shearling coat is made from processed lamb or sheepskin. The pelt is tanned, with the wool still attached to create a soft, natural ‘fleece’ material. The result is a relatively lightweight coat with excellent insulation. A good gauge of quality is based around weight – in this case, it’s the lighter the better (although this does increase the price).

Today, you’ll find the shearling coat available in a range of designs and cuts, from full-length coats to shorter aviator jackets, so simply pick what best complements your body shape and personal style.

It’s important to point out that shearling fabric does not perform well in the rain or wet, so it’s imperative you check the forecast before you leave the house. It would also be wise to regularly coat your jacket with a hydrophobic fabric spray such as Scotchgard, in case you do get caught out.

Trench Coat

Another military-inspired menswear essential, the trench coat was first designed by Thomas Burberry for use by Army officers in the trenches of the First World War. Since then, its handsome looks and water-repellant properties have seen it become a true classic, reimagined by designers the world over more times than we can count.

A proper trench coat most likely won’t be the cheapest purchase you’ll ever make, but it’s better to think of it as an investment piece – the type of thing you can wear into your twilight years and even pass down to sons and grandsons at a later date.

Buying Considerations

- Velasca Stia

- Burberry The Kensington Heritage Trench Coat

- Mackintosh Blanfield Trench Coat

- Moss Navy Trench Coat

The finest trench coats have always been made from waterproof, heavy-duty cotton gabardine. Lengths vary wildly, finishing anywhere from waist to ankle; shorter guys should pick something that hits mid-thigh, while taller men should opt for something that ends at the knee or lower.

Traditionally the trench coat featured a double-breasted cut, but single-breasted is a legitimate modern-day option. A double-breasted design will likely boast up to 10 front buttons, wide lapels, a storm flap and button-close pockets. But no matter which cut you opt for, ensure that it comes with adjustable sleeves and a belted waist for a secure, form-flattering fit.

Timeless beige or khaki is a fail-safe colour choice for your trench, although military green and mid-grey are also excellent options.

Oversized Overcoat

In recent winters, insulation has gone supersized, with long puffers, padded parkas and huge sweeping overcoats offering chunky silhouettes as well as respite from the cold. The latter seems to be gaining more traction season-by-season with woollen, robe-like styles wrapping and tying men up with belts and double-breasted cuts. The references are old military great coats, lockdown dressing gowns and Richard Gere’s Armani number from American Gigolo. Quite literally a big look, but comfortable, too.

Buying Considerations

- Wax London Magnus – Brown Herringbone Double-Breasted Wool Overcoat

- Velasca Serdes

- Todd Snyder Italian Wool Herringbone Officer Coat

- Abercrombie & Fitch Wool-Blend Double-Breasted Coat

Warmth and softness are the key features here: you’re looking for a blanket that you could feasibly wear with a suit. Wool (cashmere if you have the budget) is the preferred material, while the dimensions are exaggerated in every direction. Look for a style that reaches your knees, wraps over at the front and features big collars and lapels for extra hibernation.

Borg Trucker Jacket

Cropped jackets too often come out for autumn and are packed away again for winter because they lack the warmth required for the colder months. That’s why a version lined with borg or shearling is arguably the more sensible purchase. Warm, macho and in keeping with the never-ending workwear trend, it’s a casual piece but one you could get a lot of wear from.

Buying Considerations

- Levi’s Relaxed Fit Sherpa Trucker Jacket

- Velasca Castelrotto Trucker Jacket Beige

- CELINE HOMME Shearling Trucker Jacket

- Velasca Castelrotto

Whether you go borg or shearling is the main question here, and the answer will depend on your budget and which you think is the more sustainable. Colour-wise, the classic look is a mid-wash denim with an off-white lining, but also consider corduroy jackets in black or brown.

Fleece Jacket

The trend for practical outdoor gear is going nowhere and fleece jackets are evolving from sensible mid-layer to centrepiece outerwear, a tactile alternative to the puffer. It’ll do you no good in the rain but these thick, woolly cocoons offer a chunky barrier to the wind and cold, with outdoor specialists, workwear labels and Scandi brands all bringing their cold-weather expertise to the style.

Buying Considerations

- Percival Wool Fleece Jacket

- Wax London Tate – Navy And Khaki Shapes Jacquard Fleece Jacket

- Drake’s Green Boucle Wool Zip Fleece Jacket

- Patagonia Classic Retro-X® Fleece Jacket

As well as a shaggy pile worthy of a 70s carpet, look for practical details like zip-up pockets, elasticated cuffs and a high collar to protect your neck. Aesthetically, you can go old-school hiker with contrast breast pockets or something colourful that looks more glam rock.

If sustainability is a priority for you, look out for fleece made from recycled materials rather than virgin plastics.