In our increasingly complex economic landscape, the relationship between large firms and inflation is often overlooked. While most economics students learn that monopolies and oligopolies typically set higher prices compared to competitive markets, this truth is frequently sidelined by politicians, commentators, and the media. There is a pervasive belief that larger corporations bring about greater efficiency, which supposedly translates into benefits for consumers. However, the evidence suggests a different narrative—particularly as inflation begins to rise. The following discussion sheds light on how dominant market players can manipulate prices, thereby reinforcing the controversial notion of “greedflation.”

The authors of the original piece opted for a more subdued approach. The initial article bore the title The granular origins of inflation. But what does “granular” have to do with “big”? A look at the introductory paragraph reveals a convoluted exposition of important insights.

By Santiago Alvarez-Blaser; Raphael Auer, Head, BISIH Eurosystem Centre Bank For International Settlements; Sarah Lein, Research Network Fellow CESifo; Faculty Member Swiss Finance Institute; Full Professor of Macroeconomics University Of Basel; and Andrei Levchenko, John W. Sweetland Professor of International Economics University of Michigan, Ann Arbor Originally published at VoxEU

Traditional monetary economics attributes inflation primarily to aggregate shocks, such as variations in money supply or policy interest rates. This column presents empirical evidence indicating that inflation is significantly granular, heavily influenced by the pricing decisions of a limited number of large companies. Based on an analysis of 2.9 billion barcode-level transactions across 16 economies, we demonstrate that firm-specific shocks account for a considerable portion of inflation variability in advanced economies. Granular factors were also central to the 2021-22 inflation surge and are shown to slow down the effects of monetary policy.

The questions arise: What role do large corporations play in overall inflation? What causes and implications arise from this ‘inflation granularity’? While traditional monetary economics tends to focus on aggregate shocks, the behavior of individual firms often gets sidelined. However, research following Gabaix’s (2011) influential contribution has illustrated that shocks to significant firms can lead to broader economic fluctuations.

Recent research (Alvarez-Blaser et al. 2025) aims to clarify these dynamics by studying a multi-country home-scan dataset that encompasses nearly 2.9 billion barcode-level transactions in both advanced and emerging economies. Each data point links products to their respective firms, product categories, and retailers.

We start by demonstrating that the conditions for granularity are apparent in the dataset, revealing a concentration of expenditure: in typical advanced economies, the top ten companies account for about 41% of sales while the top ten categories comprise approximately 48%. There is also synchronized price movement within multi-product firms and across categories.

Next, we propose an additive decomposition that separates aggregate inflation into a macro component (i.e., country-level unweighted averages) alongside granular residuals at the firm and category levels. This decomposition advances the conventional granular residual framework by incorporating multiple dimensions of granularity (firms, categories, and, in some extensions, retailers). A granular residual may stem from unique shocks to large firms or from varied responses of these firms to shared shocks. 1 Our framework accounts for both driving influences, identifying which factor carries more weight in our analysis.

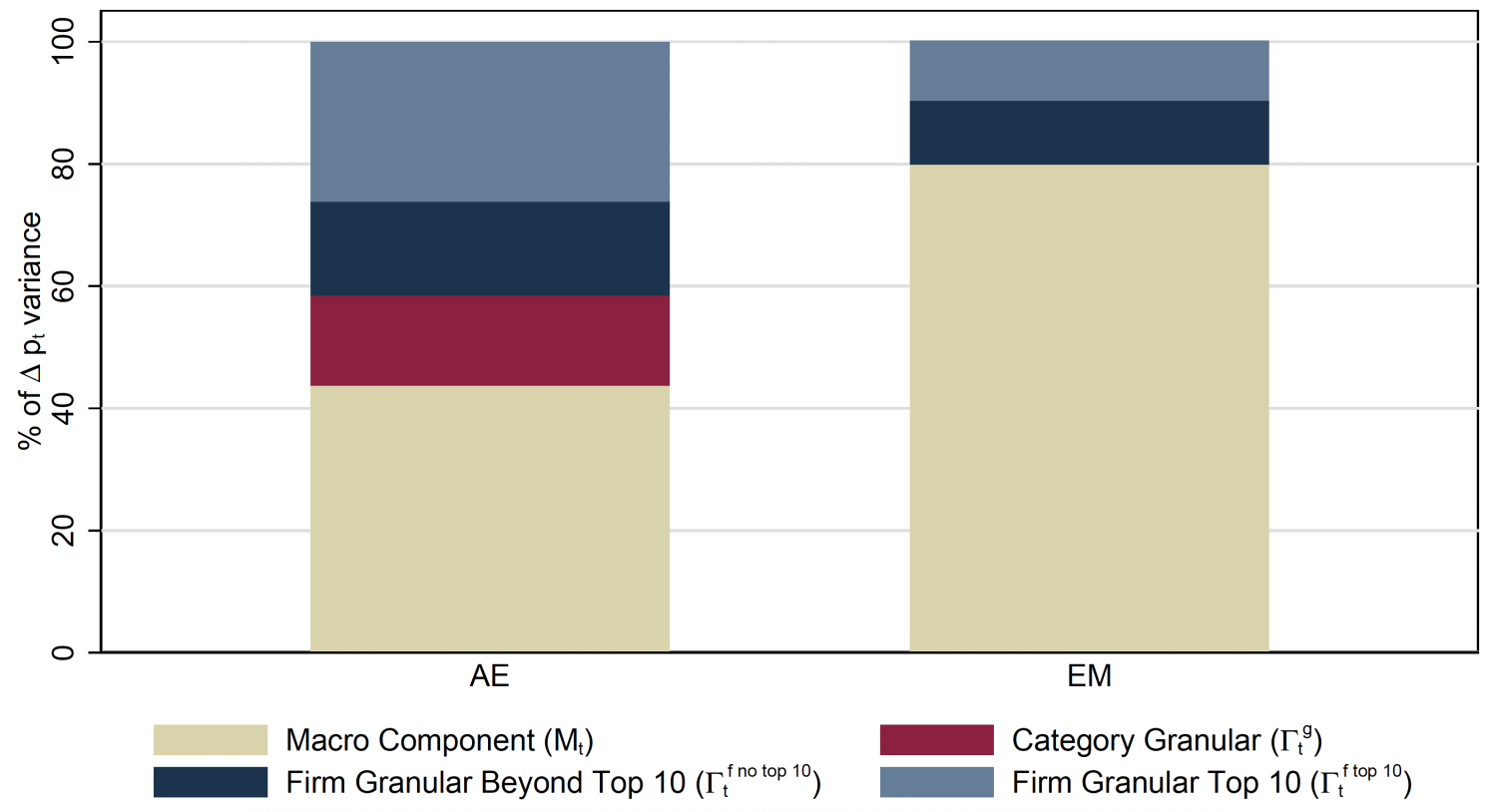

Figure 1 illustrates the significant outcomes of our investigation. At the macro level, granular components from firms and categories account for 56% of inflation variance in advanced economies from 2005-2020 (see the left side of Figure 1). The firm granular residual alone explains around 41% of inflation variance—26 percentage points from the top ten firms and 15 from sizable firms not in this elite group. Additionally, the category granular residual contributes 15% more to inflation variance (illustrated in yellow). We further analyze these granular residuals, separating them into components driven by differential responses and idiosyncratic shocks. Notably, the firm granular residual is mainly propelled by idiosyncratic shocks, while over half of the variability in the category granular residual stems from differing responses to common shocks.

Note: This figure illustrates the share of variance in aggregate year-on-year inflation attributed to each component.

Granularity is less pronounced in emerging markets (refer to the right side of Figure 1), where inflation rates are typically higher and market shares are less concentrated; the combined influence of firm and category residuals accounts for roughly 20% of inflation variance.

Market Share Concentration and Inflation Granularity

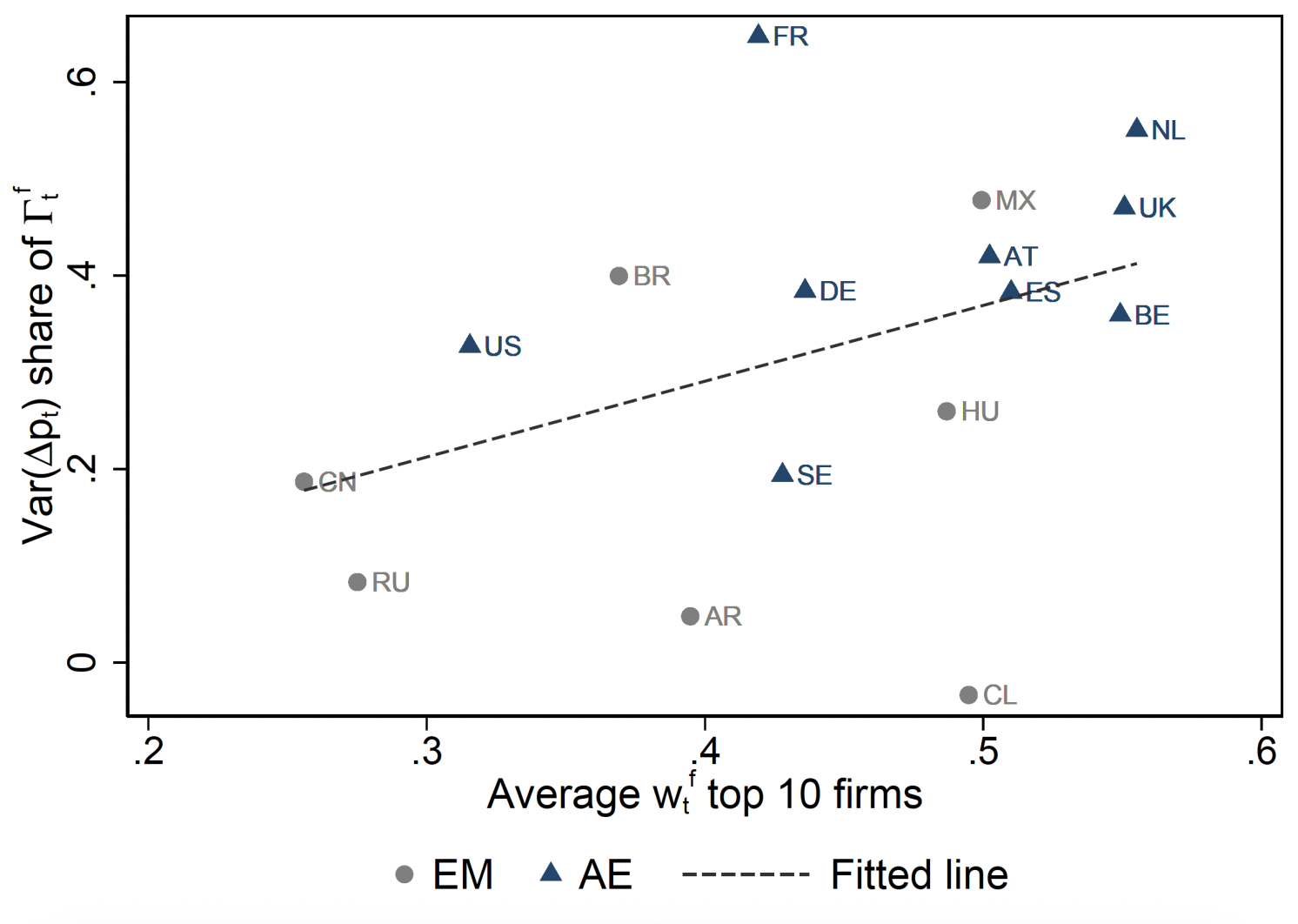

We further explore how variations in inflation granularity relate to market concentration across different countries. Specifically, we assess how granular residuals correspond to the market shares of leading firms. Figure 2 presents a scatter plot with the variance share of total inflation attributed to the top ten firms juxtaposed against their average market share across nations. A positive and statistically significant correlation emerges, indicating that granular effects are more potent in countries with greater market concentration.

Figure 2 Granularity and market concentration

Note: This figure illustrates the share of the variance in aggregate year-on-year inflation attributed to the firm granular residual vis-à-vis the expenditure share of the top ten firms. The dashed line represents a linear fit with a slope of 0.78 (robust standard error of 0.31) and R-squared of 0.16 (N=16).

This correlation suggests that trends of increasing market concentration, as noted by Autor et al. (2020), may be linked to the growing significance of firm granularity in overall inflation dynamics.

The 2021–22 Inflation Surge

In the aftermath of the pandemic, granular factors gained prominence in advanced economies. On average, the firm granular component constituted a significant portion of the inflation rates from 2021 to 2022, reflecting both unique shocks and an increased sensitivity among large firms to broader disturbances such as supply chain disruptions and energy costs. This reinforces the notion that large corporations and their synchronized pricing strategies amplify macroeconomic shocks.

Figure 3 illustrates these trends in Germany, showing overall inflation (solid line) divided into the unweighted macro average component (dashed line) and the granular components (sum of firm and sectoral contributions). It is evident that granular forces played a larger role during the inflationary surge.

Figure 3 Germany: Aggregate retail inflation and granular components – retailer perspective

Note: This figure displays year-on-year inflation alongside its components. Further country-specific data and figures are available in the main paper.

Implications for Monetary Policy Effectiveness

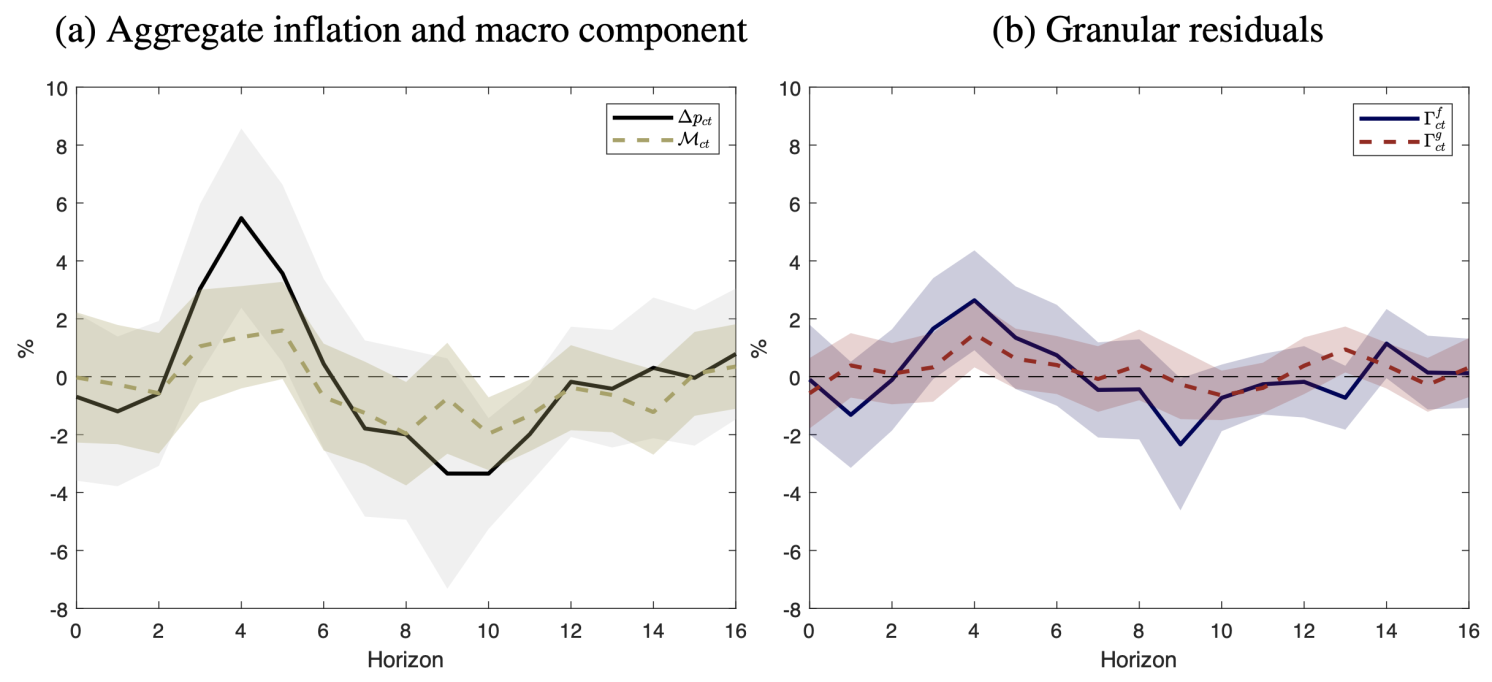

A critical finding is that granularity modifies how inflation reacts to contractionary monetary policy. Local projection estimates for both the US and euro area indicate that aggregate inflation exhibits a short-run ‘price puzzle,’ consistent with earlier studies like Christiano et al. (1999). This initial increase is primarily driven by granular components, which account for approximately three-quarters of the short-term rise. In contrast, the macro component does not exhibit significant inflationary response for about five quarters post-monetary policy change, subsequently declining in line with standard economic predictions. This indicates that heightened market concentration and pricing behavior among major corporations can delay disinflation, undermining immediate monetary policy effects. In environments with a higher concentration of market shares, large firms’ actions significantly influence how financial strains and input-cost shocks are transmitted through the economy.

Figure 4 Impulse response functions for aggregate inflation and components

Notes: Panel (a) presents quarterly local projection results for overall year-on-year inflation and the macro component. Panel (b) showcases the corresponding results for both firm-level and category-level granular residuals. Shaded areas indicate 90% confidence intervals derived from HAC standard errors.

Conclusion

This analysis reveals that inflation in advanced economies is significantly shaped by granular factors, predominantly driven by a limited number of large firms. In contrast, granular residuals appear less critical in markets characterized by lower concentration and higher inflation rates, as seen in emerging economies. These granular influences contributed notably to the inflation surge post-COVID, with the firm-level component accounting for roughly one-third of inflation between 2021 and 2022 in advanced economies.

The findings underscore the importance of granular elements that extend beyond traditional macroeconomic factors in understanding inflation and its implications for monetary policy effectiveness. A practical takeaway is that detailed pricing data from large firms and products offer vital insights for monitoring inflation trends. Initiatives like the ECB’s Daily Price dataset and the BIS Innovation Hub’s Project Spectrum endeavor to create tools for real-time analytical capabilities, enhancing the accuracy of inflation assessments (BIS Innovation Hub 2025).

______

- Due to limitations in observing prices without knowing marginal costs, we cannot differentiate observed price changes into adjustments in markups versus cost alterations. Therefore, our findings do not directly address the ongoing debate surrounding whether large firms disproportionately increased their markups during the 2021-22 inflation surge (the so-called ‘greedflation’ or ‘seller’s inflation’ discussion). Current empirical evidence suggests that markup adjustments were not a significant driver of inflation increases (e.g., Alvarez-Blaser et al. 2024).

See original post for references