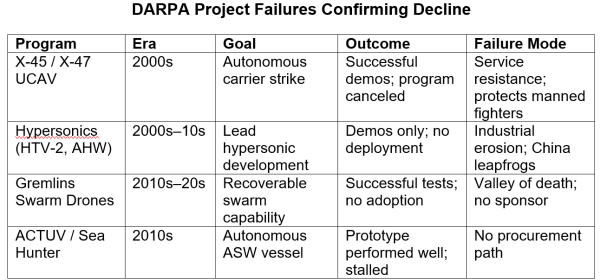

This article explores the transformation of the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) from an innovative powerhouse in American technology to an agency hampered by political caution, industrial decline, and bureaucratic inertia. By highlighting its peak years marked by revolutionary developments such as ARPANET, stealth technology, GPS, and computer advancements, we investigate the changes that have led to DARPA producing fewer groundbreaking capabilities. Our analysis identifies three principal shortcomings: political interference, risk aversion in industry, and a system of incentives that discourages program completion.

DARPA was established in 1958 following the Soviet Union’s launch of the Sputnik satellite, with the mission to restore America’s technological dominance and to ensure that the U.S. led in defense innovation. Free from traditional military bureaucracy, DARPA was tasked with taking bold risks in long-term research, focusing not on enhancing existing systems but on developing entirely new military capabilities.

DARPA’s Golden Age

From the 1960s through the 1990s, DARPA thrived during an era characterized by its remarkable ability to transform theoretical concepts into practical systems that changed the world. At the height of the Cold War, the U.S. benefitted from a robust network of industrial laboratories, prestigious universities, and top-notch engineering firms that could take DARPA’s experimental visions and turn them into operational realities.

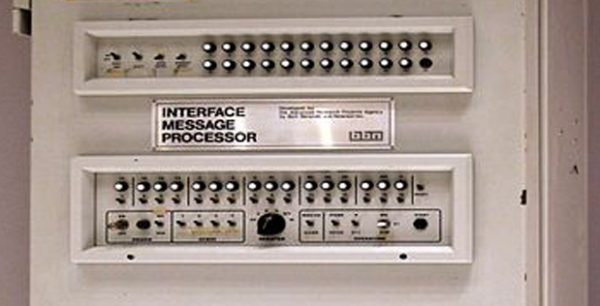

A prime example is ARPANET, the precursor to today’s internet—a forward-looking investment in networked packet-switching communication that evolved over the years into what we now know as the global digital economy. During this period, DARPA’s greatest asset was not merely its funding or secrecy but its close relationship with an industrial ecosystem capable of integrating radical ideas into military assets, a capacity that the U.S. currently lacks.

ARPANET IMP – the start of something big

Have Blue prototype – precursor to F117

Political Restrictions

In the early 1990s, DARPA’s mission shifted considerably after the removal of director Craig Fields, who had expanded the agency’s focus to include dual-use technologies with commercial relevance, especially in semiconductors. His dismissal sent a clear message: while DARPA could innovate, it could not do so in ways that altered America’s industrial landscape. This change was reflective of a growing neoliberal ideology that discouraged government from “picking winners and losers,” effectively limiting DARPA’s ability to undertake projects that could reshape industries.

Throughout the 1990s, these constraints tightened, further restricting DARPA’s exploration of politically sensitive or disruptive technologies. The emergence of the Total Information Awareness (TIA) counterterrorism research program in the early 2000s attracted significant political backlash, further underscoring the limitations on DARPA’s activities. Although DARPA managed the TIA office and funded advanced data-analysis tools, it never implemented surveillance systems or utilized personal data. The controversy surrounding TIA made it evident that crossing political lines now resulted in institutional repercussions. By the mid-2000s, DARPA’s role as a catalyst for national-scale technological advancement had diminished significantly.

Industrial Decline

The decline of America’s diverse industrial base and the consolidation of defense contractors fundamentally changed what DARPA could achieve. In previous decades, DARPA could pass a revolutionary design to firms like Northrop, Lockheed, or Hughes and expect rapid iteration fueled by willing engineers. Today, however, a handful of mega-prime contractors dominate the field, and their business models prioritize predictability, lengthy contract cycles, and incremental upgrades to existing systems. Consequently, revolutionary DARPA prototypes are now seen as threats to the revenue streams of established companies, leading to many potentially groundbreaking projects being abandoned not due to technical failure but because of a lack of industrial interest in their development into operational systems. This represents the second critical failure.

Perverse Incentives

While DARPA continues to produce remarkable prototypes, the current defense acquisition system lacks a viable pathway to transition these innovations into operational capabilities. Projects that showcase successful demonstrations—like autonomous carrier aviation, hypersonic systems, or unmanned surface vessels—often stall due to the need for inter-service consensus, stable multi-year funding, and the willingness to disrupt established doctrines. The current system incentivizes launching new programs rather than completing existing ones; it favors prolonging timelines over deploying capabilities and encourages commissioning studies rather than building operational forces. This constitutes the third structural failure: a system where success is seen as risky and failure is often more advantageous.

The Valley of Death

Defense experts refer to the perilous divide between a successful prototype and a fully funded military program as the “valley of death.” In theory, DARPA is supposed to transfer promising technologies to military services for adoption. However, in reality, these transitions have become nearly impossible. Contemporary acquisition guidelines demand multi-year budgets, strict requirements, and alignment with service doctrines—all of which heavily favor existing platforms over transformative new capabilities. Consequently, in recent years, DARPA projects that demonstrate clear technological success frequently stall without any service willing to sponsor their procurement or revise existing force plans. The valley of death has grown to function as a structural barrier—an area where groundbreaking work is acknowledged, discussed, and studied, only to be quietly shelved.

Case Study: The UCAVs That Worked

DARPA’s X-47 Unmanned Combat Air Vehicle (UCAV) program showcased that a stealthy, autonomous strike aircraft could operate from an aircraft carrier, perform coordinated missions, and fulfill roles traditionally assigned to manned aircraft in contested environments. Despite achieving significant technical milestones, the program was halted at the critical transition point requiring service endorsement. The Navy redefined the mission to prioritize surveillance over strike capabilities, thus protecting the budgets and institutional prominence of manned aviation. Without a service willing to advocate for procurement, the initiative fell into the valley of death. Similarly, the parallel X-45 program for the Air Force, which also demonstrated effective autonomous strike operations, met the same fate for comparable reasons. Today, rivals like Russia and China are advancing toward operational deployment of high-performance, stealthy UCAVs such as the S-70 Okhotnik and GJ-11 Sharp Sword, the very category the U.S. initially pioneered with its X-45 and X-47 programs before discontinuing them.

X-47 UCAV – rejected by naval aviators

Russian Sukhoi S-70 Okhotnik UCAV – Note resemblance to X-47

Conclusion

The decline of DARPA is not merely due to internal shortcomings; it is symptomatic of a deteriorating national defense landscape. During the ARPANET era, the U.S. possessed the political will, industrial vitality, and bureaucratic flexibility to harness DARPA’s bold ideas. Today, while DARPA still envisions innovative projects, those aspirations often clash with political caution, industrial risk aversion, and an incentive structure that penalizes success while rewarding stagnation. Although DARPA’s creativity remains vibrant, the surrounding environment has faltered, diminishing the nation’s ability to transform groundbreaking ideas into operational capabilities.