Yves here. In the past, we cautioned that Brexit would incur considerable economic costs for the UK. The establishment of a hard border led to trade friction and raised the costs for both importers and exporters dealing with the EU, ultimately affecting consumers as well. Financial institutions relocated significant jobs to the continent to comply with EU regulations. The UK also lost its position within a large economic bloc, leading to the challenge of negotiating its own trade agreements, which are unlikely to match the favorable terms of previous EU arrangements. Furthermore, offices of EU research institutions were shuttered. This is just a glimpse of the substantial losses incurred.

The following analysis estimates the overall damage inflicted on the UK and compares it with previous assessments. The results reveal a situation even worse than anticipated, as these costs have proven to be persistent rather than temporary losses that the UK could potentially recover over time.

By Nicholas Bloom, William Eberle Professor of Economics Stanford University; Philip Bunn, Senior Technical Advisor in the Structural Economics Division Bank Of England; Paul Mizen, Professor in Economics and Vice Dean, Research, at King’s Business School King’s College London; Pawel Smietanka, Research Economist Bank Of England; Senior Economist Deutsche Bundesbank; and Gregory Thwaites, Research Director Resolution Foundation; Associate Professor University Of Nottingham. Originally published at VoxEU

The UK is revisiting the reasons behind its sluggish economic growth since the mid-2010s. This column explores the implications of the decision to exit the European Union in 2016. Drawing from almost a decade’s worth of data since the referendum, the authors blend macroeconomic simulations with insights from microeconomic data. Their findings indicate that by 2025, Brexit had decreased UK GDP by between 6% and 8%, with this decline unfolding gradually over the years. Investment, employment, and productivity were all adversely affected, rooted in factors such as heightened uncertainty, lower demand, diverted management attention, and increased misallocation of resources.

The UK once again finds itself entangled in discussions regarding its slow economic growth since the mid-2010s. Real wages have stagnated, investment levels remain weak, and productivity growth has been disappointing. A variety of factors contribute to this situation—from the lingering effects of the global financial crisis to the impacts of the Covid‑19 pandemic and the energy price surge following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. However, one significant aspect has been at the forefront of policy discourse for nearly a decade: Brexit.

A wealth of literature has highlighted the potential long-term costs of leaving the EU Single Market and Customs Union (HM Treasury 2016, IMF 2016, Van Reenen et al 2016). Early analyses using macro data also indicated a substantial downturn in UK GDP and trade (Born et al. 2019, Dhingra and Sampson 2022, Springford 2022, Haskel and Martin 2023, Freeman et al. 2025). VoxEU has provided a crucial platform for this research and ongoing debate. Our contribution revisits this topic nearly a decade after the referendum, merging macroeconomic and microeconomic evidence into a cohesive framework while contrasting actual outcomes with pre-referendum forecasts.

In a recent paper (Bloom et al. 2025), we integrated micro data from the Decision Maker Panel (DMP), a survey of UK firms, with publicly available macro data to estimate Brexit’s impact. Our findings are as follows:

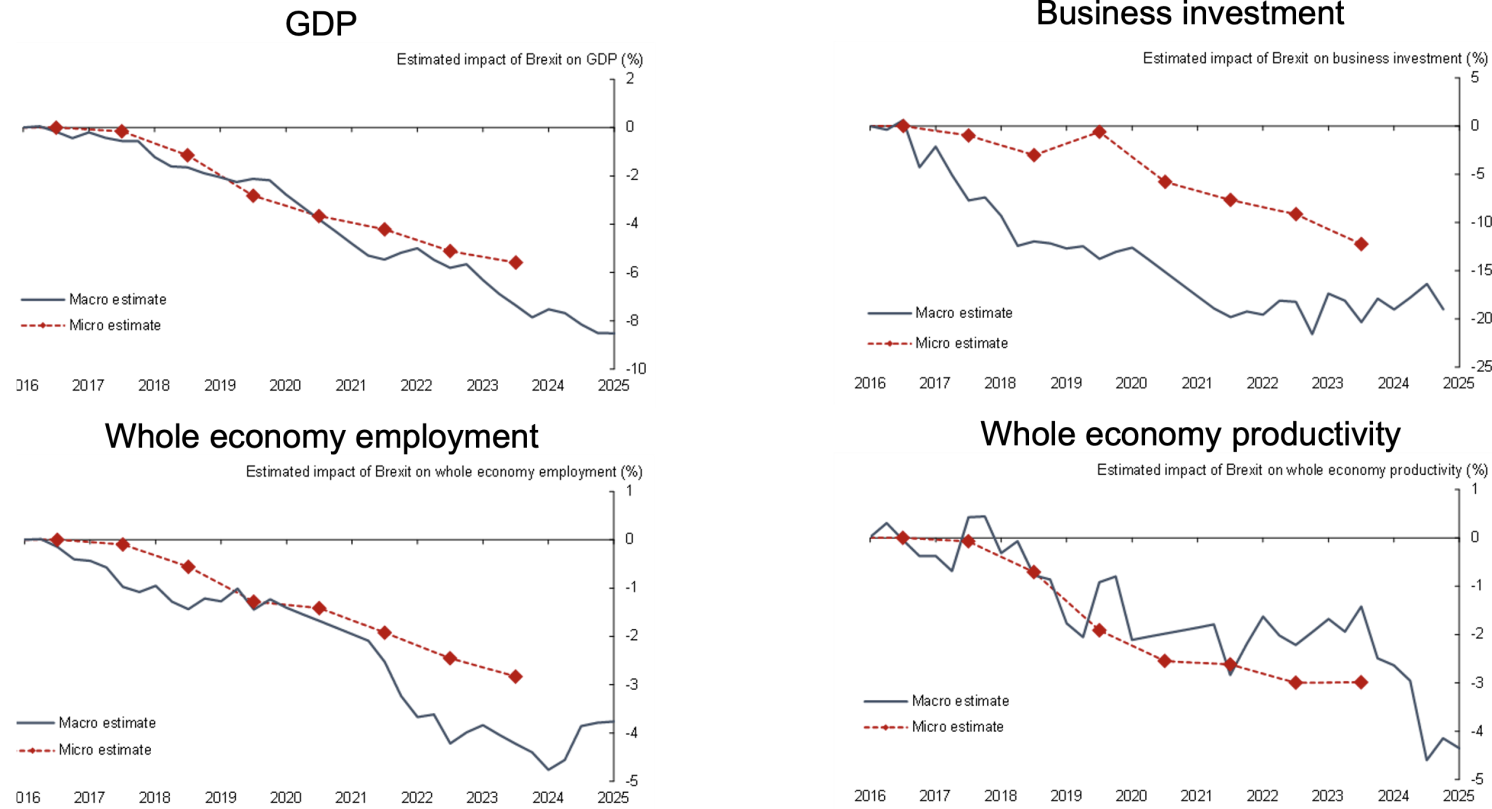

- Brexit has had a significant and enduring effect on the UK economy. By 2025, we estimate that UK GDP per capita was 6-8% lower than it would have been without Brexit. Business investment was down by 12-18%, while employment and productivity were both reduced by 3-4%.

- These losses accumulated over time. The effects were not evident in 2017-18 but steadily increased across the following decade, driven by persistent uncertainty, heightened trade barriers, and firms reallocating resources away from productive activities.

- Economists were generally correct about the loss magnitude but misjudged the timing. The pre-referendum consensus forecast of a 4% long-run GDP loss closely aligned with the actual loss after five years, but failed to account for a larger loss in the longer term.

Evaluating Brexit’s Impact: Macroeconomic Evidence

Our initial approach contrasts the UK’s performance post-2016 with that of similar advanced economies. This method, frequently utilized on VoxEU to evaluate the repercussions of Brexit and other policy changes (e.g., Born et al. 2019), establishes a projection of how the UK economy might have fared without Brexit based on experiences from other countries, then evaluates how actual UK outcomes deviated from this baseline.

We analyzed quarterly data from 33 advanced economies (the EU27, the US, Canada, Japan, Iceland, Norway, and Switzerland) spanning from 2006 to 2025, focusing on GDP per capita, business investment, employment, and labor productivity. Due to the absence of a single ‘correct’ weighting method for comparator countries, we explored five different approaches: unweighted average, GDP-weighted average, gravity-weighted average (GDP divided by distance), trade-weighted average, and a formal synthetic control. Our primary estimates represent the average across these five methods, which reach similar conclusions regardless of the weighting scheme employed.

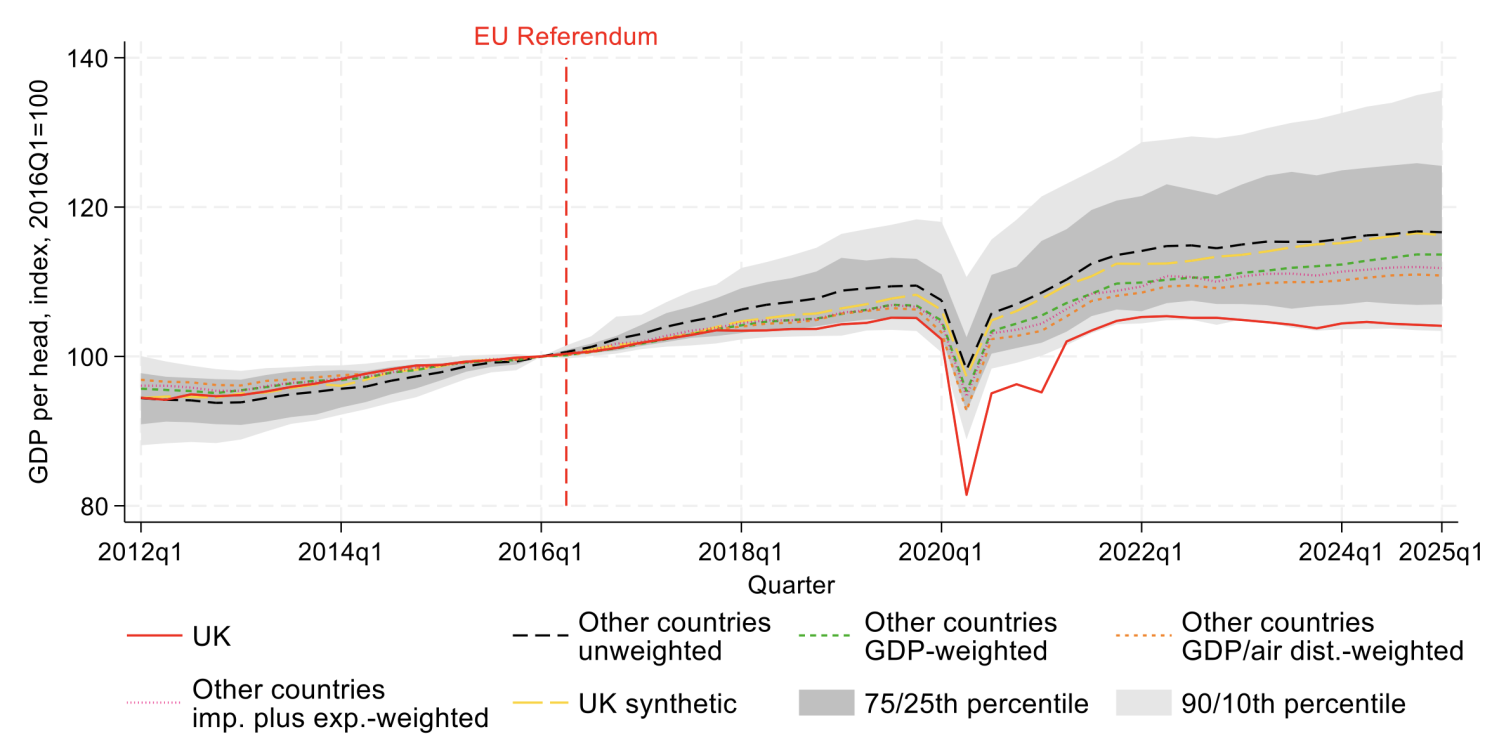

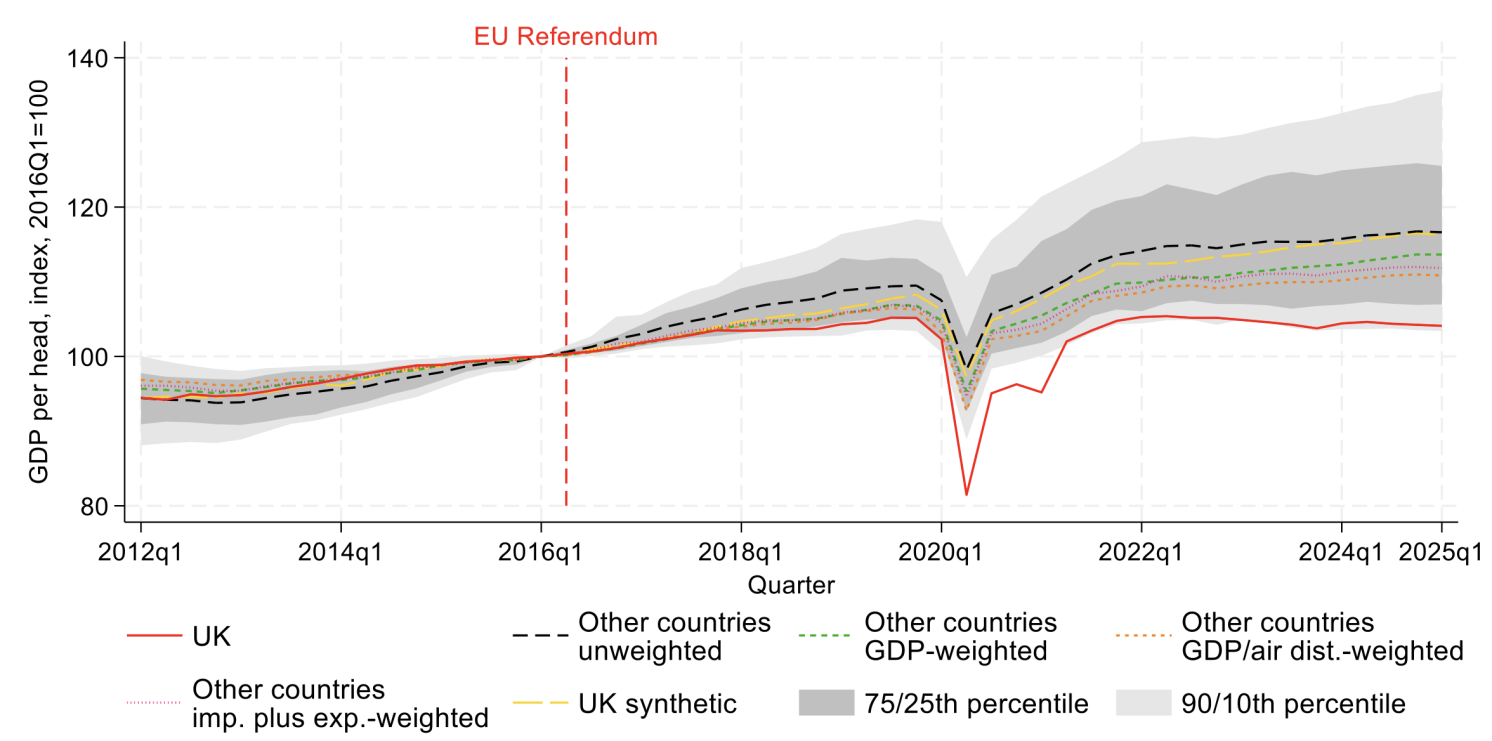

Figure 1 illustrates that prior to the referendum, the growth rate of UK GDP per capita was on par with that of the comparison group. However, following 2016, these trends diverged. By early 2025, UK GDP per capita had lagged by 6-10 percentage points compared to similar economies, with a total growth of only about 4% over the entire period. Our central estimate—averaging across these five approaches—indicates that the UK GDP per capita has been approximately 8% lower than that of comparable advanced economies since 2016.

Similar patterns emerge for other key indicators:

- Business investment experienced a severe downturn. The UK shifted from being a strong performer pre-referendum to lagging behind post-referendum. By 2025, business investment was 12-18% below the levels suggested by comparator economies.

- Employment growth has faltered, though to a lesser degree: we estimate a shortfall of around 4% compared to the counterfactual.

- Labor productivity was approximately 4% lower than the comparison group by 2025.

Figure 1 GDP per capita cross-country comparison

These macro comparisons are not without their caveats. The underlying premise is that the UK would have mirrored the performance of a weighted average of other countries in the absence of Brexit. However, this assumption may not hold. The Covid‑19 pandemic and energy crisis impacted countries differently; various policy responses, including the UK’s furlough scheme and energy bill subsidies, also varied significantly. Additionally, Brexit likely had negative consequences for EU trading partners, which could downwardly bias our estimates. Therefore, we complement the macro analysis with insights derived from micro-econometric data sourced from firms based in the UK.

These macro comparisons are not without their caveats. The underlying premise is that the UK would have mirrored the performance of a weighted average of other countries in the absence of Brexit. However, this assumption may not hold. The Covid‑19 pandemic and energy crisis impacted countries differently; various policy responses, including the UK’s furlough scheme and energy bill subsidies, also varied significantly. Additionally, Brexit likely had negative consequences for EU trading partners, which could downwardly bias our estimates. Therefore, we complement the macro analysis with insights derived from micro-econometric data sourced from firms based in the UK.

Micro Evidence

The unexpected outcome of the Brexit vote in 2016 provides an opportunity to adopt a difference-in-differences methodology using firm-level data.

Our micro analysis capitalizes on the fact that Brexit’s effects varied according to firms’ pre-referendum exposure to the EU. Utilizing the Decision Maker Panel—an extensive monthly survey of UK firms—we formulated a comprehensive measure of prior EU exposure that encompasses six dimensions: share of exports to the EU, share of imports from the EU, reliance on EU migrant labor, exposure to EU regulations, proportion of directors who are EU nationals, and EU ownership. These survey data were matched with company accounts data.

Companies with higher EU exposure experienced more rapid growth prior to 2016. However, this trend reversed post-referendum. After controlling for firm and time fixed effects and accounting for Covid-related shocks, our micro-based findings indicate the following overall impacts:

- Investment growth diminished, resulting in a 12% shortfall in business investment levels by 2023/24.

- Employment growth decreased by approximately 0.5 percentage points annually, translating to a 3-4% drop in employment by 2023/24.

- Total factor productivity (TFP) growth declined by around 0.5 percentage points each year, contributing to a 3-4% reduction in within-firm TFP by 2023/24.

The micro approach presents a different set of challenges than the macro approach. The closer connection to EU exposure aids in more accurately identifying the causal effects of Brexit. However, it necessitates the assumption that firms with lower EU exposure were unaffected by Brexit’s consequences, while they may have faced negative spillovers (e.g., through demand or supply chains) or positive spillovers (e.g., labor market advantages for unexposed firms). Overall, the macro and micro estimates regarding the impact on GDP, investment, employment, and productivity are generally aligned, with macro estimates typically representing a larger effect (Figure 2).

Figure 2 The estimated impact of Brexit

Why Did the Damage Take So Long To Become Apparent?

Our analysis identifies four primary channels through which Brexit influenced the UK economy, all of which unfolded gradually:

- Enduring uncertainty. Brexit established an unusually prolonged phase of policy uncertainty. Our Brexit Uncertainty Index, derived from the DMP, gauges the percentage of firms identifying Brexit as one of their top three sources of uncertainty. Following the referendum, this index surged and remained high well into the period following the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) implementation in 2021. Investment is particularly vulnerable to uncertainty, and our firm-level regressions indicate that this uncertainty channel largely explains the post-2016 downturn in investment.

- Heightened trade costs and diminished demand. Although the TCA maintains zero tariffs and quotas on a significant portion of UK‑EU trade, leaving the Single Market and Customs Union has introduced considerable non‑tariff barriers. Other studies have shown sharp declines in UK–EU goods trade around 2021, alongside persistent disruptions to supply chains and services trade (Dhingra and Sampson 2022, Freeman et al. 2025). A decrease in expected demand, particularly in tradable sectors, has emerged as a key factor in the decline of employment growth.

- Reduced innovation and diverted management resources. Productivity within firms may have suffered due to cutbacks in investment aimed at enhancing productivity, coupled with management time being shifted from other tasks to facilitate Brexit preparations.

- Shifts away from highly productive, internationally competitive firms. The companies most exposed to the EU generally rank among the most productive, and these firms experienced the most significant adverse effects from Brexit.

Together, these factors elucidate why the economic consequences of Brexit have unfolded as a slow-burning phenomenon. Rather than a sudden collapse, the UK experienced a protracted process of negotiation, transition, and implementation, with uncertainty and adjustment costs extending over nearly a decade.

How Did Pre-Referendum Forecasts Perform?

The Brexit referendum presents a unique context in macroeconomics to contrast ex-ante forecasts with ex-post realities. The IMF (2016) outlined predictions made by academic and professional economists regarding the long-term impacts of Brexit on UK GDP. The average forecast among respondents estimated a 4% GDP loss compared to remaining within the EU, with most of this impact expected to materialize within a five-year timeframe.

Our findings indicate that this consensus forecast held up reasonably well over a five-year span: we observe a GDP shortfall of 4-6% by 2021. However, by 2025, the loss deepened to 6-8%. In essence, while economists were overall correct regarding the direction and scale of the long-term impact, they underestimated the drawn-out nature of the Brexit process and, therefore, the persistence of related uncertainty and adjustment costs.

This insight carries broader implications for assessing macroeconomic forecasts surrounding significant political events. The Brexit experience suggests that accurately predicting the economics isn’t sufficient; understanding the political economy of implementation—encompassing the potential for delays, renegotiations, and partial reversals—can substantially influence both the timing and eventual magnitude of economic effects.

Lessons for Future Trade Fragmentation

The UK’s departure from the EU is an unprecedented occurrence. No other significant economy has willingly retreated from such deep integration with its neighbors. Nonetheless, the mechanisms identified in our study are likely to hold relevance for future instances of trade and migration fragmentation, including the introduction of tariffs, sanctions, and stricter immigration controls in various regions.

Our research illustrates that withdrawing from global trade and production networks can incur considerable and enduring economic costs, often accruing gradually rather than manifesting instantaneously. In the case of Brexit, the UK economy faced substantial repercussions.

See original post for references