Greetings from Yves. At some point, the current trajectory of housing prices will reach a limit defined by Stein’s Law: that which cannot continue will not. Factors such as demographic trends and the public’s affordability constraints will eventually restrict price increases. However, the slowdown may take some time to manifest.

Article by Yujiang River Chen, Bevil Mabey, Associate Professor in Economics at St Catharine’s College, University of Cambridge, and Coen Teulings, Emeritus Distinguished Professor of Economics at Utrecht University. Originally published at VoxEU

The significant rise in house prices across numerous advanced economies has sparked populist movements and social turmoil. This column suggests that agglomeration externalities are driving urbanization and knowledge spillovers, resulting in high location premiums that contribute to the increase in housing prices. Strategies to tackle the affordable housing crisis include constructing smaller homes in urban areas, enhancing public rail transport for commuting, and appropriately pricing parking for city residents.

The rapid escalation of house prices in most OECD nations has caused widespread concern (see e.g. The Economist 2024, Wolf 2021). The crisis of affordable housing has become pivotal in recent elections and is fueling a global populist backlash. Political leaders and policymakers are struggling to devise effective measures to address what many view as a significant market failure and social crisis.

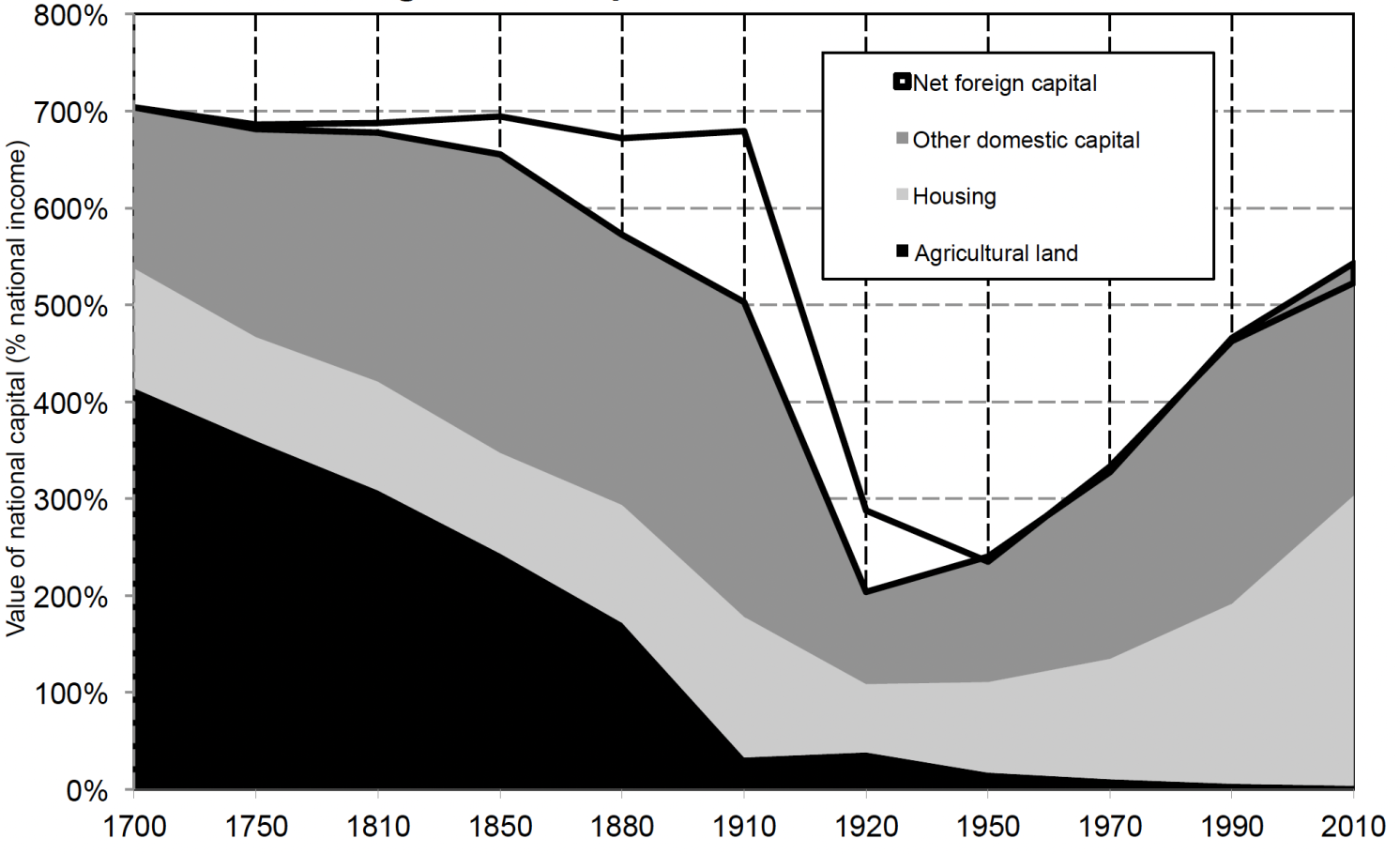

Data from Piketty’s (2014) work Capital in the 21st Century reveals that the increasing share of housing in the total capital stock has been observable since the 1960s and 1970s (refer to Figure 1). This trend poses a complex question. One would typically expect house prices to align with construction costs over time. Although there may be some rise in relative construction costs, it is unlikely that this can fully account for the long-term upward trend.

Figure 1: Housing’s Increasing Share of the Capital Stock in Recent Decades

a) UK

b) France

Source: Piketty (2014)

We propose an alternative explanation for the growing share of residential real estate in the capital stock. Much like real estate agents’ famed mantra regarding property value—location, location, and location—agglomeration externalities encourage urbanization and create substantial location premiums that are reflected in housing values. These premiums create a disconnect between construction costs and house prices, which we contend is the primary driver of rising house prices. This disparity is deeply entrenched in the extraordinary growth of capitalist economies over the last two centuries, particularly within OECD countries. It is linked to the increasing proportions of research and development on one side and marketing and sales on the other (Baldwin and Ito 2021), both of which heavily rely on knowledge spillovers.

Human Capital and Economic Growth

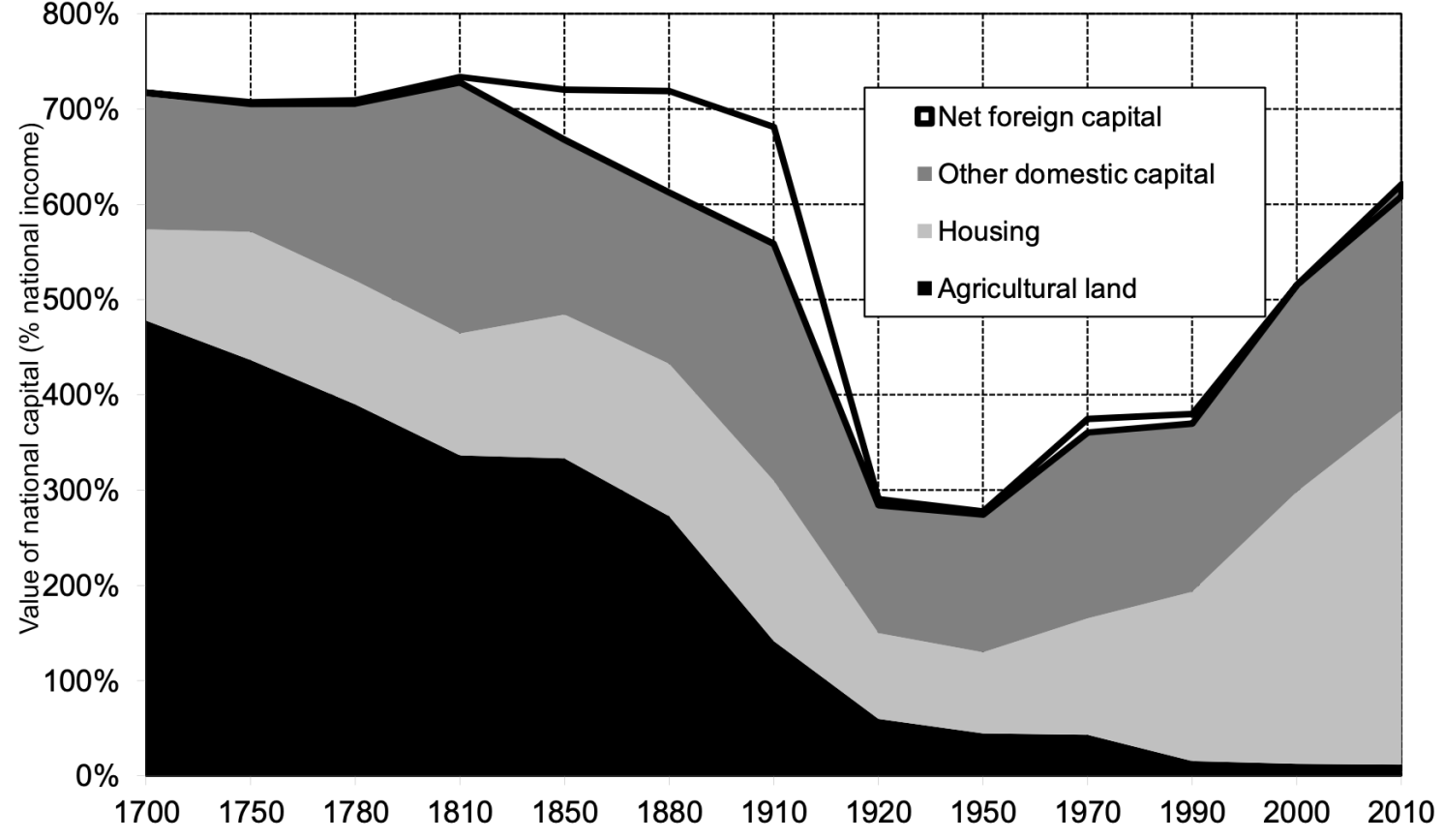

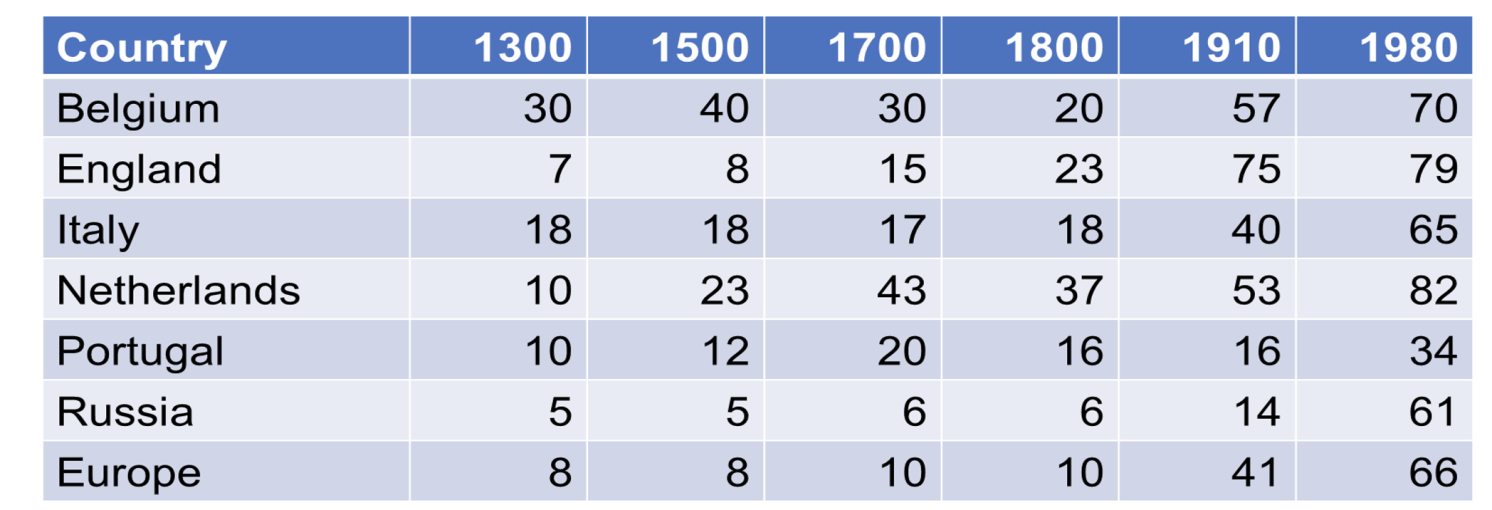

At the dawn of the capitalist and industrial revolutions around 1800, the differences in GDP per capita worldwide were relatively minimal, roughly a factor of four. Notably, this was not far removed from what had been observed in the wealthier regions of the Roman Empire nearly two millennia earlier. For two centuries, the Netherlands was double the wealth of most other regions, serving as a precursor to the economic phenomena that would unfold in subsequent centuries. As the capitalist revolution intensified in the 19th century, first in the UK and then rapidly spreading to Western Europe and the US, GDP per capita surged dramatically in these areas, with little impact observed elsewhere. This divergence has persisted over the past two centuries, leading to the stark disparities in GDP per capita we see today, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Strong Correlation Between GDP per Capita and Average Years of Education Across Countries, 2023

Source: Our World in Data based on UNDP, Human Development Report (2025); Eurostat, OECD, IMF, and World Bank (2025)

In a seminal work, Lucas (1988) posed questions regarding this occurrence, as standard economic theories would anticipate convergence rather than divergence of GDP per capita. Given the ease of technology transfer, disparities in GDP per capita should reflect differences in capital stock per worker across nations. However, countries with high capital intensity would exhibit lower returns on capital, disincentivising investment in these regions compared to their low-capital counterparts, leading to convergence—an assertion contradicted by the data. This suggests that technology is not nearly as transferable as previously presumed, a notion hinted at in Arrow’s (1962) analysis on the economics of learning by doing: new technologies are acquired mainly through practice rather than mere inspiration.

This investigation underscored localized knowledge spillovers, where proximity to sites of innovation becomes essential. Lucas emphasized the role of cities as centers of agglomeration facilitating these spillovers, referencing Jacobs’ influential (1961) book The Death and Life of Great American Cities. In collaborative research with Rossi-Hansberg (Lucas and Rossi-Hansberg, 2002), they delve into the implications of urban structure, particularly the presence of a commercial central business district (CBD) surrounded by residential areas. Their model has been extensively utilized, for instance, in Heblich et al. (2020) when analyzing the emergence of London as a modern metropolis around 1850 and by Ahlfeldt et al. (2015) when exploring the consequences of the Berlin Wall’s division for five decades.

The localized impact of human capital is further reflected in Figure 2, which correlates GDP per capita with years of education. Data suggests a public return of approximately 50% for each year of education—significantly higher than the standard estimate of about 10% for private returns. Similar findings from Gennaioli et al. (2013) utilizing within-country regional variations affirm that high human capital workers cluster in specific regions, resulting in elevated GDP per capita in those locales. While the raw data indicates correlation, we acknowledge that it does not prove causation, a topic we will address later.

Cities and Human Capital

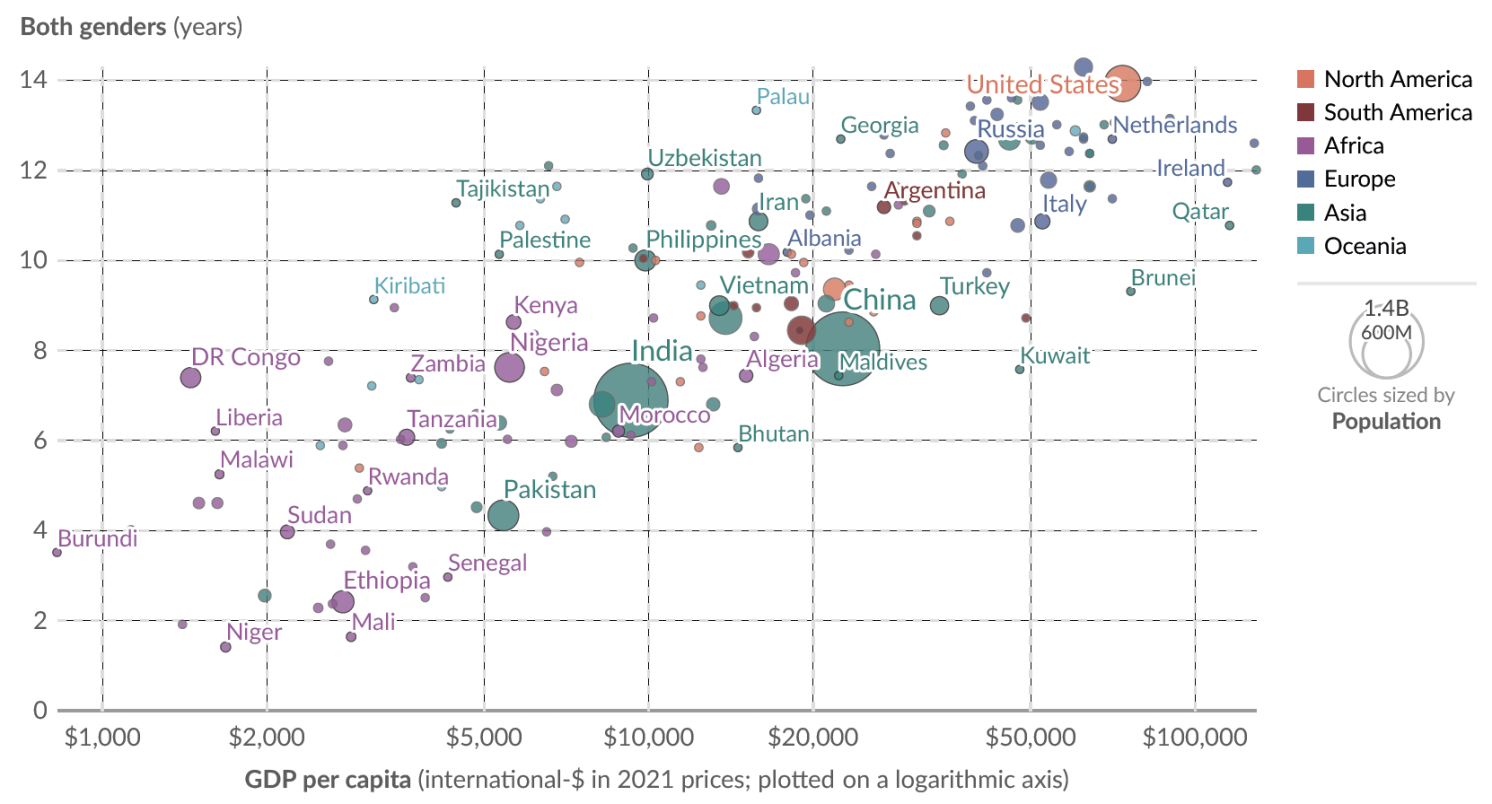

Consistent with Lucas’ analysis, cities have historically been pivotal to economic advancement. Periods of exceptional economic prosperity have correlated with urbanization, whereas downturns have seen a decline in urban growth. This dynamic is effectively illustrated in Table 1, utilizing data compiled by Bairoch (1988). Belgium emerged as the world’s most urbanized nation at the zenith of its textile industry from 1300 to 1500. Subsequently, the Dutch Republic surpassed Belgium, leading to a decline in its urbanization rates. As noted earlier, the Netherlands enjoyed unparalleled prosperity during the subsequent two centuries, becoming the most urbanized country globally, with Amsterdam at the forefront as a major port and financial hub. Although the Netherlands maintained its status as the wealthiest nation well into the 18th century, its preeminence, along with urban growth, gradually diminished until the UK overtook it around 1850, coinciding with its rapid industrialization.

Table 1: Urbanization in European Countries Aligned with Economic Growth

Source: Teulings and Huysmans (2025), adapted from Bairoch (1988)

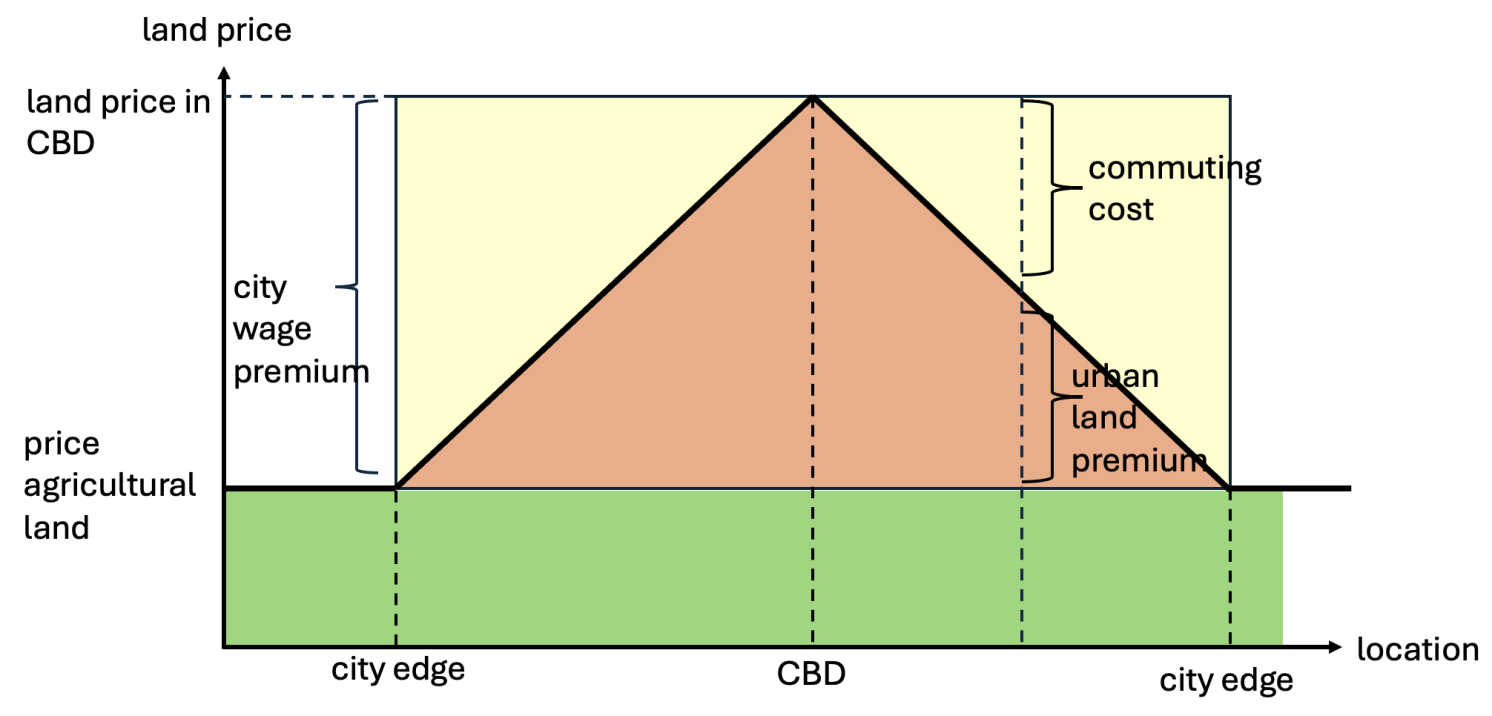

Figure 3 simplifies the dynamic of Lucas and Rossi-Hansberg’s model. The horizontal axis represents locations with the CBD at the center. The vertical axis signifies land prices and wages, which are treated equally for simplicity. Green areas indicate wages in rural settings, while the higher wages in the CBD reflect the advantage of agglomerating workers at a single point to facilitate knowledge spillovers. Because workers require residential space and cannot all reside in the CBD, they occupy the suburbs and commute to work. The yellow triangle outlines commuting costs, which increase as distance from the CBD grows: the farther away, the higher the commuting expenses. Consequently, properties near the CBD hold greater value because residents save on commuting costs. At the urban periphery, wage differentials are balanced by the commuting costs, illustrating the disconnect between house prices and construction expenses. Urban development is constrained at the city limit due to full land occupancy, while building beyond that threshold proves unprofitable because commuting costs from those locations surpass the city wage premium.

Figure 3: A Simplified Model of a City

Source: Teulings and Huysmans (2025).

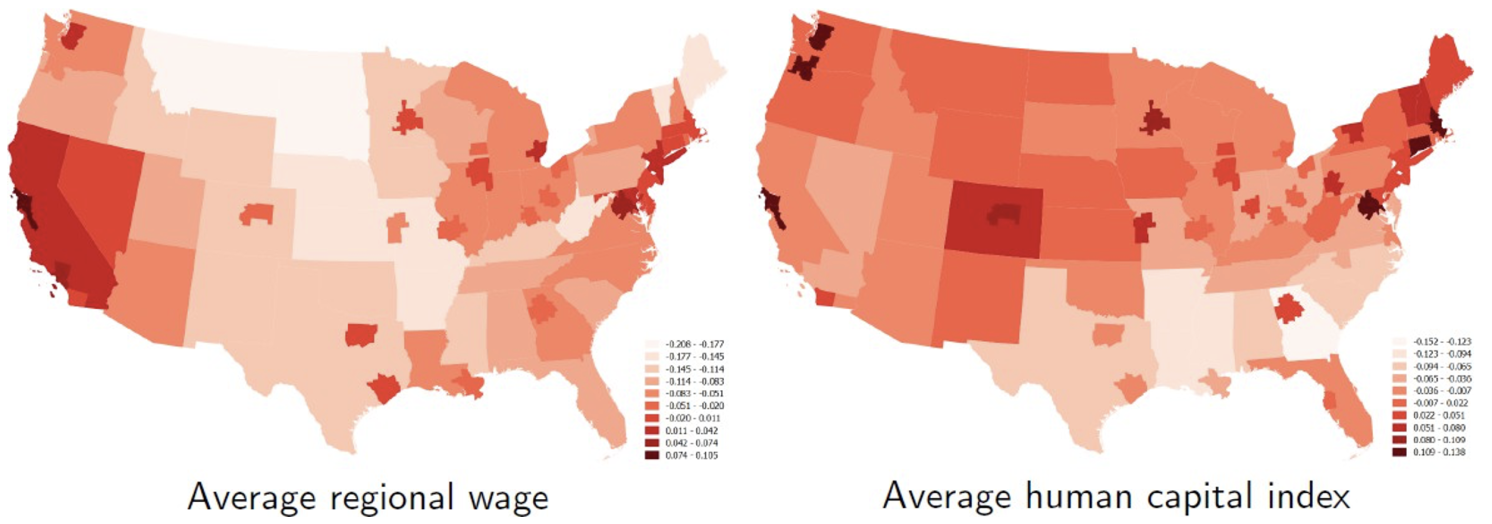

This spatial configuration, characterized by a commercial CBD and surrounding residential suburbs, enhances knowledge spillovers by densely clustering a large number of workers in a confined space, contrasting with the geographical dispersion of employment often seen in rural areas. Knowledge spillovers tend to favor high human capital workers, who gravitate towards cities, as corroborated by Gennaioli et al. (2013). Figure 4, sourced from Chen and Teulings (2025), illustrates this phenomenon in the US across 34 cities and 47 rural areas. Findings indicate cities like San Francisco, Boston, and San Jose exhibit higher human capital per worker than other locales, with the average urban setting outperforming its rural counterpart (left panel). The same observation extends to wage data (right panel).

Figure 4: Human Capital Concentrated Regionally, Particularly in Urban Areas

Source: Chen and Teulings (2025)

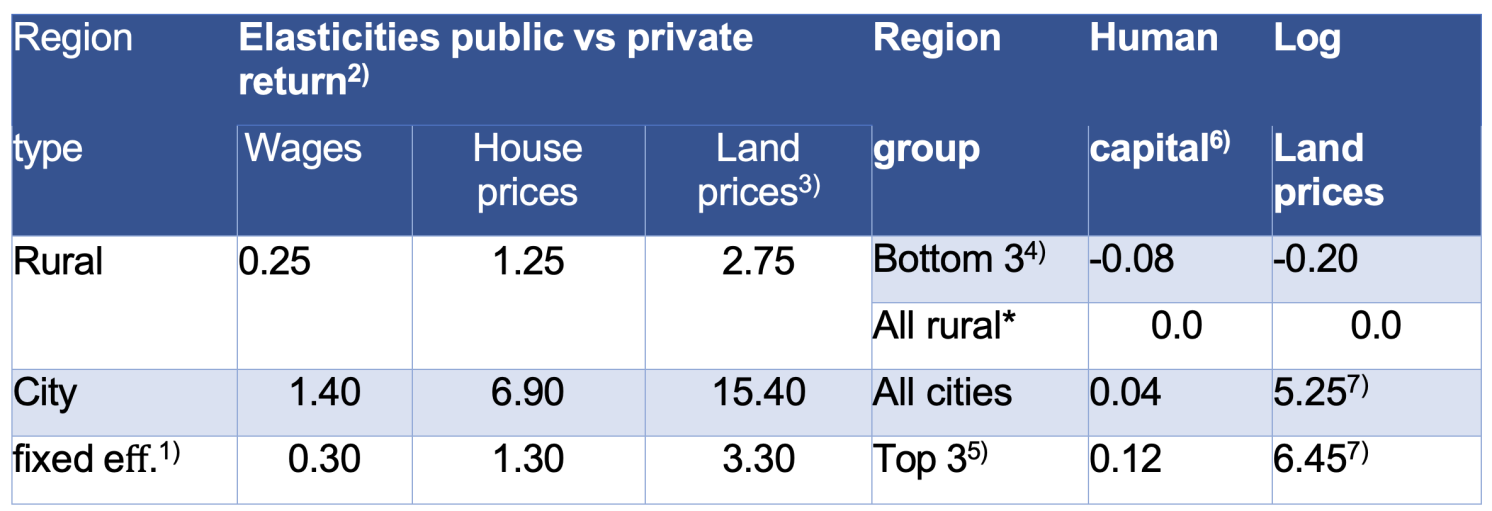

Utilizing this model, Chen and Teulings (2025) regressed individual log wages against both individual and regional human capital as explanatory factors. The impact of individual human capital captures its private return, while regional human capital reflects its public return.

Table 2 presents the regression results. The public return adds an estimated 25% to the private return in rural areas and more than doubles it in urban settings (see column 2). Two well-documented statistical challenges affect the interpretation of the regression coefficients. First, the effect of regional human capital could proxy unobserved individual human capital, thereby skewing the public return upwards. Second, a shared latent variable might explain why specific regions offer higher wages and why high human capital workers choose to reside there. Even after correcting for these issues, the adjustments likely underrepresent the public return.

Therefore, workers’ human capital bestows positive externalities that augment the earnings of their coworkers within their region. The urban form amplifies these externalities by clustering these workers together, as indicated by the Lucas and Rossi-Hansberg (2002) model. A natural experiment during the 1974 Carnation Revolution in Portugal substantiates these insights, revealing that the subsequent modernization propelled Lisbon’s specialization in high human capital sectors (Teulings and Vieira 2004).

Table 2: The Public Return to Human Capital and Land Prices in Rural Areas and Cities

Note: *: reference category. Additional notes: (1) Fixed city effect in a wage regression incorporating individual wages and regional mean human capital; (2) Public return on average regional human relative to the private return; (3) Utilizing estimated coefficients from Table 8, λz from Table 7, pr = vr – lr according to equation 8; (4) Comparisons among Louisiana, Georgia, and Mississippi; (5) Top three cities: San Francisco, Boston, and San Jose; (6) Expressed in relation to the private return on this capital; (7) Incorporating the fixed city effect

Source: Chen and Teulings (2025)

When making housing decisions, workers factor in these positive externalities, favoring regions with elevated human capital, especially cities with a highly educated workforce, which consequently boosts their pay. An inherent counterbalance exists that prevents everyone from migrating to the city with the highest human capital: property prices, or the underlying land costs. Adjustments occur to equalize desirability between regions. Workers indeed earn higher wages in cities—especially those with a well-educated labor pool—but the cost of renting or purchasing housing in these metropolitan areas is greater. To validate this theory, we regress regional log house prices against average regional human capital (see Table 2, column 3). Given that housing services comprise only a small fraction of workers’ budgets, the influence of human capital on house prices must be approximately five times more pronounced to counteract the positive impact on wages, as empirically evidenced. However, with such elevated housing costs in urban settings, workers often compromise on housing services to redirect funds to other consumption. As a result, residential density is markedly higher in cities compared to rural areas, further amplifying the effect on land prices (see column 4). The last two columns outline the implications for human capital and land prices across four distinct regions: rural areas and cities, as well as the lowest three regions in terms of human capital (Louisiana, Georgia, and Mississippi) and the highest three cities (San Francisco, Boston, and San Jose), with rural areas serving as the reference point. Land prices in the leading cities are reported as 6.45 log points (equating to a factor of 600) higher than in average rural regions. Employing a one-third land share in housing costs suggests a square meter of housing is eight times pricier in the top three cities compared to the average rural area.

We apply the model to two counterfactual scenarios. First, assessing the impacts if cities did not exist, leading to a rural-oriented structure with scattered employment and significantly reduced knowledge transfers. Second, evaluating the implications of human capital being evenly distributed across the nation rather than clustered in specialized regions conducive to knowledge spillovers. In both instances, projections indicate GDP would be roughly 10% lower; in terms of welfare impact, the effect is more muted since portions of the city wage premium compensate for commuting costs.

Policy Implications

The significant rise in housing prices observed over the last fifty years, as documented by Piketty (2014), does not come as a shock; it can be readily elucidated through the increasing relevance of knowledge spillovers and human capital externalities that have substantially influenced the growth of capitalist economies since 1800. These regional externalities generate economic rents predominantly captured by landowners located near CBDs. Advocates may suggest implementing a Henry George-style taxation on these rents, converting housing services at these central locations into potential revenue sources for governments, though housing in urban centers is likely to remain limited and consequently expensive for individual residents.

Figure 4 indicates that urban areas can expand until the point where the city wage premium matches commuting costs. Lange and Teulings (2024) argue that vacant lands at the periphery of thriving cities possess considerable option value due to the irreversible nature of construction. It may be prudent to delay construction rather than build prematurely at insufficient densities. This option value contributes to a divide between the city wage premium and commuting costs at the outskirts, driving up property prices at the city’s edge. Delays in response to rising house prices become more pronounced with increasing city growth rates, enhancing the option value and exacerbating construction delays. Our analysis yields little optimism for those advocating for immediate large-scale construction at city borders as a means of boosting residential floor space and mitigating price increases.

Further, the Lucas-Rossi-Hansberg model suggests that individuals often acquire more floor space than is efficient (Rossi-Hansberg 2004). The elevated house prices in cities reflect the benefits an additional worker derives from residing near the CBD and accessing the knowledge spillovers accrued from a concentrated workforce in the CBD. However, these prices do not account for the advantages that the existing workers in the CBD receive from the additional spillovers generated by the new worker. Including this externality in property pricing would diminish overall floor space consumption, thereby facilitating more efficient knowledge spillovers.

A burgeoning body of literature (e.g., Glaeser et al. 2005, Duranton and Puga 2023) has begun to elucidate the ramifications of excessive regulation on new construction. Such regulations can inhibit development. Beyond institutional inertia, insiders—current residents—may resist regulatory reforms, as new developments could diminish their property values due to either the negative externalities associated with nearby construction or the broad equilibrium effects from an increased housing supply depressing prices of existing real estate.

The validity of this position hinges on the political jurisdiction governing these regulations. Regulation set on a broader scale, encompassing the entire urban agglomeration, might not be unduly restrictive since it would account for all pertinent externalities. Cities tend to implement strategies to attract corporate headquarters and similar entities, benefiting from the knowledge spillovers. They frequently invest in transportation infrastructure for commuting to the CBD, exemplified by the redevelopment of Canary Wharf in London. Some cities even impose minimum density guidelines on new urban developments, aligning with theoretical predictions.

However, regulations established at lower political levels may not account for these externalities. 1 Local agglomeration benefits tend to dominate—for instance, the affluent neighborhoods’ desire to retain lower-income residents. Minimum lot size regulations serve as a classic tool for this purpose. Though this may hold true for some high-end neighborhoods, its overall significance at the city level, especially in Europe where city planning is relatively centralized, is open to debate.

This analysis presents several policy alternatives that may help alleviate public outcry regarding the lack of affordable housing. Since prices per square meter are unlikely to decrease, the first recommendation is to construct smaller homes within urban settings. Those desiring larger homes would need to relocate to more distant suburbs.

The second recommendation is to enhance efficient public rail systems for commuting. This strategy is motivated by two key factors. Improved public transportation diminishes commuting costs per kilometer; consequently, assuming a constant city wage premium, this expansion leads to an outward shift in the city’s boundaries (refer to Figure 3). Additionally, private car transport is significantly land-intensive relative to public rail transport, stemming from both road construction and parking needs at workplaces in the CBD and residences in the suburbs. Rail options, being land-efficient and scalable, are particularly well-suited for larger cities. This land competition offers commercial and residential spaces less opportunity and thus reduces the chance for knowledge transfers. Jane Jacobs championed her career protesting against the construction of the Cross Bronx Expressway, and cities like Amsterdam and Copenhagen have succeeded in curtailing car usage. Major urban centers such as London and Paris are following suit.

The third policy correlates with the second. Ossokina et al. (2025) demonstrate that parking fees in shopping centers align closely with local land prices and are roughly consistent with the expected rate of return on land, ranging between 5% for commercial enterprises evaluating their land usage between parking, retail space, or residential development. Nevertheless, most cities considerably subsidize parking for residents. In larger cities, where car ownership is no longer a practical necessity, the rationale behind municipalities providing nearly complimentary parking spaces to residents—while the actual costs range between €1,000-€5,000 annually, linking roughly to an asset value between €20,000-€100,000—raises questions. By offering minimal or free parking, this privilege becomes tied to home ownership, comprising 10-20% of a home’s total value. This expenditure is effectively squandered for individuals without cars. Why should those without vehicles financially support car owners?

For references, see the original post.