In this article, we will explore the complex and often contentious dynamics surrounding the potential for the United States to exploit Venezuelan oil. While some may see prospects for increased energy resources, the reality suggests a much more complicated situation that deserves careful consideration. The motivations behind U.S. actions in Venezuela cannot be distilled into simple explanations, making this topic ripe for critical analysis.

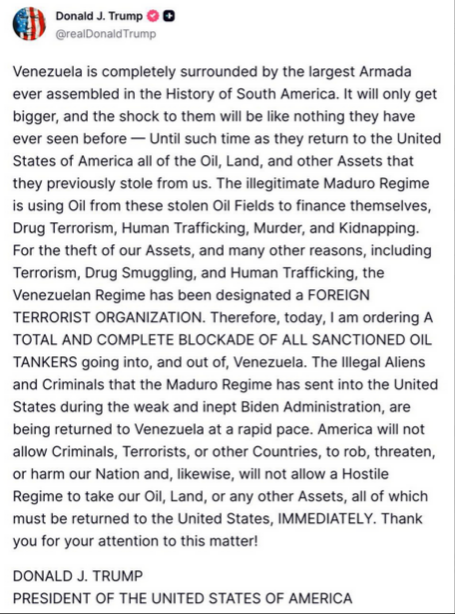

In a nutshell, this piece delves into the reasons why Venezuelan oil lacks significant strategic value for the United States. It highlights the substantial investments needed to revitalize the country’s oil infrastructure, a process that would take years to achieve. Meanwhile, President Trump has altered his narrative, shifting from a focus on narco-terrorism to the idea of reclaiming oil and other assets through military intervention in Venezuela (remember that a blockade is considered an act of war):

Recall that after the justifications for the Iraq war—centered on weapons of mass destruction—disintegrated, the administration relied on a series of shifting pretexts, even as many observers contended that oil was the real motivation. At the time, Iraq boasted the world’s second-largest proven oil reserves and offered highly coveted light sweet crude. Although the U.S. retains considerable control over Iraq’s oil exports, it has been slow to develop the country’s oil infrastructure. I can’t recall the exact source, but I once read that major oil companies remained wary regarding the extent of U.S. exploitation of Iraqi resources.

A 2024 article in The Cradle describes the current situation:

In July, the Iraqi Central Bank ceased all foreign transactions in Chinese Yuan under significant pressure from the U.S. Federal Reserve. This halt followed a brief period where Baghdad permitted Yuan trading, a move intended to mitigate the overwhelming U.S. restrictions on Iraq’s access to U.S. dollars. While this Yuan-based trade excluded Iraq’s oil exports, which remained in dollars, Washington perceived it as a threat to its financial dominance. The underlying reason for U.S. influence in Iraqi financial policies traces back to the 2003 invasion.

Since President George W. Bush signed Executive Order 13303 on May 22, 2003, all revenue from Iraq’s oil sales has been directly funneled into an account at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

A 2012 Al Jazeera article suggested that even though Western firms secured critical oil concessions post-war, their results fell short of expectations, aligning with the theory that Iraq’s resources were not exploited efficiently.

Many readers may be quite familiar with this chapter of history, so any additional insights would be welcomed. However, my understanding suggests that the later theories—that Iraq served primarily as a stepping stone toward subduing Iran, with oil as a secondary objective—hold merit.

If the potential U.S. war against Venezuela isn’t motivated by narco-terrorism or oil, what, then, is the driving force? One possible justification might be to subdue Cuba, but such an approach seems excessively costly. This looks to be a poorly conceived strategy aimed at restoring perceived American strength by casting a weaker nation into chaos. Recall Trump’s futile attempts to pressure India with secondary sanctions to stop importing Russian oil; he found an awkward way out there as well. Trump suggested to European allies that he would impose sanctions on Russian oil buyers if they didn’t comply, allowing an easy retreat when they refused. What’s his exit strategy from this misguided escalation?

John Mearsheimer, in a recent conversation with Judge Napolitano, expressed confusion over the predicament Trump has found himself in but conveniently downplayed the initial question of why this confrontation began. Starting around the 2:34 mark in the discussion:

Mearsheimer: It seems the administration is scrambling to find a way out of the corner it’s painted itself into regarding Venezuela. We decided early on that Venezuela was a significant threat to the United States and could be dealt with casually. But that assumption has proven incorrect.

The Trump administration is searching for options to handle this issue, which largely means removing the Maduro government and alleviating the predicament we’ve created. Initially, Trump claimed that the CIA was operating within Venezuela, which escalated further into destroying vessels and inflicting casualties. He even hinted at possible land invasions or a blockade of Venezuela’s airspace, all these strategies reflecting the administration’s inability to effectively confront the Maduro government while saving face. They are entwined in a real dilemma—hence the recent ship seizure and the declaration of a blockade.

Now, to the main discussion.

By Matthew Smith, Oilprice.com’s Latin America correspondent. Originally published at OilPrice

- Accusations from Venezuelan and Colombian leaders aside, the significant growth in U.S. domestic oil production lessens the strategic necessity for Washington to take control of Venezuela’s oil fields.

- The U.S. Gulf Coast refining industry has largely moved away from Venezuelan heavy crude due to facility closures and a shift to alternative suppliers like Canada, Mexico, and domestic shale sources.

- Revitalizing Venezuela’s outdated oil infrastructure to reach major export levels would take over a decade and require billions of dollars in investment, making military action economically untenable for the United States.

Trump’s substantial naval buildup off Venezuela and the threat of invasion has been branded by the nation’s disputed president, Nicolas Maduro, as a blatant attempt to seize oil. Other Latin American leaders, particularly Colombia’s Gustavo Petro, echo similar sentiments. A history of U.S. interventions to secure vital fossil fuel resources, coupled with Venezuela possessing the world’s largest proven crude oil reserves of 303 billion barrels, supports this narrative. However, various factors suggest that a U.S. military operation is not merely cloaked in the guise of securing Venezuela’s oil.

Maduro has not only withstood Trump’s stringent sanctions, but has leveraged them to fortify his hold on power. Even significant civil unrest and military coup threats have failed to dismantle Maduro’s authoritarian rule. By 2021, the Venezuelan economy began recovering, driven by growing oil exports counter to U.S. sanctions and Iran’s stable supply of condensate, which provided expertise and material to rejuvenate Venezuela’s ailing refineries amidst an ongoing energy crisis.

Despite Trump’s issuance of a $50 million bounty and escalating sanctions, Maduro has successfully maintained power. In August 2025, the White House amassed a considerable naval presence in the southern Caribbean, ostensibly to halt cocaine trafficking to the U.S. Despite unclear objectives, many analysts interpret Trump’s aggressive posture as an attempt to oust Maduro. Venezuela’s disputed president has publicly accused Washington of intending to use military force to confiscate the country’s vast oil resources, which he claimed they cannot illegally take. President Petro, in a CNN interview, asserted that oil lies at the heart of U.S. intentions, stating, “(Oil) is at the center of the issue. Trump’s logic revolves around that; he cares little about the democratization of Venezuela, let alone the narco-trafficking.”

Following the U.S. Coast Guard’s seizure of a sanctioned tanker, the M/T Skipper, laden with 1.9 million barrels of Venezuelan heavy crude, tensions escalated further. Both Maduro and Petro accused Washington of piracy and theft. Maduro decried the action as an act of international piracy, firmly stating that Venezuela would not become a U.S. oil colony. Petro added, “They have seized a vessel; this is piracy, and they are manifesting their motives—oil, oil, and oil.”

Both leaders intensified their rhetoric, despite the Skipper operating in violation of U.S. sanctions. The tanker carried 1.9 million barrels of Merey, Venezuela’s main export-grade heavy oil, with an API gravity of 15 degrees and 2.15% sulfur content, destined first for Cuba and then for Asia, with China and India being key purchasers of U.S.-sanctioned oil. The vessel’s repeated transport of sanctioned Venezuelan crude led the U.S. Coast Guard to obtain a court-issued warrant, which expired just days after the vessel was seized. This marked the first tanker confiscated by the U.S. since the implementation of severe sanctions on Venezuelan crude oil in 2019.

The White House and State Department have consistently refuted assertions that military intervention aims to secure control of Venezuelan oil. U.S. officials maintain that the mission, named Southern Spear, focuses on curbing the flow of drugs and preventing illegal immigration. While these goals are certainly part of the military operation, indications suggest that the U.S. agenda may also aim to apply pressure on a largely unpopular Maduro to facilitate a return to democracy in Venezuela. Moreover, the rationale behind claims asserting the necessity of controlling Venezuela’s vast oil reserves is exceedingly weak.

As the world’s foremost petroleum producer, the U.S. doesn’t require forcible acquisition of Venezuela’s extensive oil reserves. Over the past 20 years, U.S. output has surged remarkably. The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) data reveals that production more than tripled, from 4.2 million barrels per day in September 2005 to 13.8 million barrels per day by September 2025. Furthermore, forecasts suggest that U.S. oil production could escalate to 18 million barrels per day by the early 2030s. This extraordinary expansion is backed by the record growth of U.S. oil reserves, doubling from 23 billion to 46 billion barrels between 2003 and 2023.

The phenomenal growth of U.S. petroleum output and reserves over the past two decades, attributed to the shale boom, is so significant that by 2019, the U.S. had emerged as a net energy exporter. In fact, by September 2025, the U.S. EIA reported oil imports of just under 250 million barrels, a far cry from the 397 million barrels imported the same month two decades prior. This shift is crucial because, unlike the period from 1958 to 2018, when the U.S. depended more on foreign oil, the nation is no longer economically bound to overseas petroleum imports.

Some analysts argue that despite the impressive growth in U.S. oil reserves and production, there remains a strong demand for Venezuela’s low-cost heavy crude. In the 1980s, Venezuela’s heavy crude became an enticing option for U.S. Gulf Coast refineries, owing to lower prices compared to WTI and Brent benchmarks, abundant production volumes of 2 to 3 million barrels per day, and proximity to the U.S. Refining facilities on the Gulf Coast were often tailored to process heavy sour crude from Venezuela, rendering them incapable of efficiently refining lighter, sweeter grades. This unique relationship made Venezuela’s crude vital for maintaining U.S. energy security, contributing to assertions about Trump’s aggressive approach and the planned seizure of Venezuela’s oil reserves.

However, while these facts rang true three or four decades ago, they are far from the current reality. Declining refining margins and soaring operational costs prompted a drastic contraction in the U.S. refining sector from the mid to late 1990s. As a response, numerous higher-cost Gulf Coast refineries, particularly those focused on heavy sour crude, either closed or shifted to more profitable alternatives. The EIA data illustrate that 27 Gulf Coast refineries with a combined distillation capacity of 832,426 barrels per day permanently shut down between January 1, 1990, and January 1, 2025. Others pivoted to process lighter, sweeter grades of crude or to handle biofuels.

Since the early 2000s, Gulf Coast refineries reliant on heavy sour crude have had to seek alternative sources. Canada, followed by Colombia and Mexico, became essential suppliers. A confluence of decreased oil prices, governmental malfeasance, and stricter U.S. sanctions heavily impacted Venezuela’s production. From 1997, just before Hugo Chavez’s presidency began, to 2015, petroleum output fell from 3.5 million to 2.7 million barrels per day. In 2020, it plummeted to an all-time low of 570,000 barrels per day.

Although oil production in Venezuela has seen some recovery—especially with U.S. company Chevron receiving a restricted license to operate in the sanctioned nation—shipments to the U.S. remain at all-time lows. In September 2025, the U.S. imported merely 3 million barrels of Venezuelan crude, less than 1/13 of the 41 million barrels received in the same month two decades ago. These figures starkly illustrate the diminishing relevance of Venezuelan oil within a considerably reduced U.S. refining industry, particularly as domestic output continues to grow. Concurrently, the number of operational U.S. refineries has decreased from 148 in 2005 to 132 at the start of 2025.

Even if the U.S. were to take control of Venezuela’s extensive oil resources, the task of rebuilding its devastated infrastructure would require at least a decade and tens of billions of dollars in investment. Reports indicate that Venezuela’s current production, which OPEC data places at 934,000 barrels per day, is a fraction of the nearly 3 million barrels produced 30 years ago. An investment of $58 billion would only raise production to a modest range of 1 to 2 million barrels per day, insufficient for Venezuela to re-establish itself as a major exporter. To achieve this goal, continuous investments of $10 to $12 billion annually for at least a decade—or potentially much longer—would be necessary to refurbish corroded wellheads, pipelines, processing facilities, and storage systems.