In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, the world witnessed the ongoing evolution and expansion of shadow banking. This phenomenon poses significant risks to global financial stability, as explored by Satyajit Das. Despite regulatory assurances, shadow banking has grown more complex and pervasive, drawing in players from across the globe, including China. Below is a comprehensive examination of the current state of shadow banking, its implications, and the emerging challenges it presents.

By Satyajit Das, former banker and author of multiple technical works on derivatives, including Traders, Guns & Money: Knowns and Unknowns in the Dazzling World of Derivatives (2006, 2010), Extreme Money: The Masters of the Universe and the Cult of Risk (2011), and A Banquet of Consequence – Reloaded (2016, 2021). His latest book focuses on ecotourism: Wild Quests: Journeys into Ecotourism and the Future for Animals (2024). This is an expanded version of a piece originally published on November 28, 2025, in the New Indian Express print edition.

During the 2008 crash, the role of unregulated financial institutions—such as structured investment vehicles, asset-backed commercial paper issuers, and hedge funds—contributed to financial turmoil. Predictably, regulators pledged to rein in ‘shadow banks’—often referred to as ‘market-based finance’ or ‘non-bank financial institutions.’ Despite these promises, effective control has been elusive.

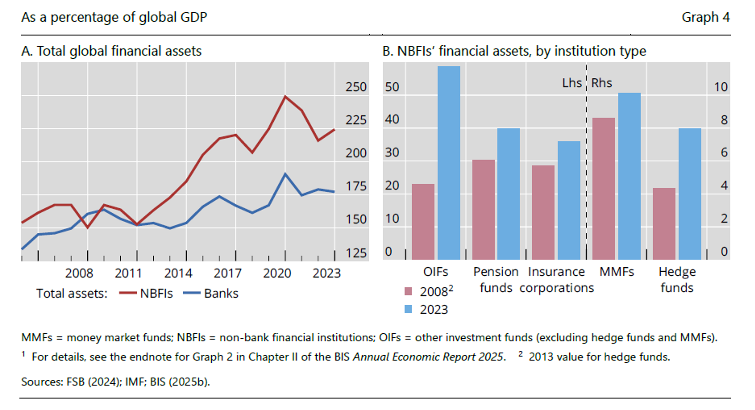

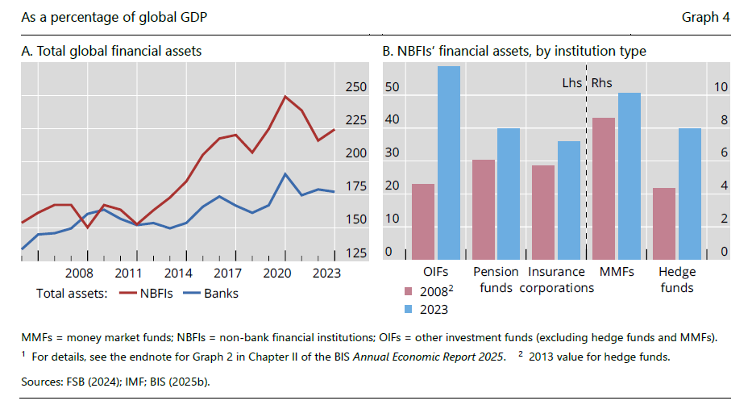

Since 2008, the share of shadow banks in global financial assets has notably risen. According to recent data, the graph below illustrates that the assets held by insurers, private credit providers, hedge funds, and other non-bank financial entities amounted to approximately $257 trillion in 2024, marking a 9.4 percent increase. In contrast, banks saw a more modest growth of 4.7 percent, bringing their total assets to just over $191 trillion.

By 2024, the total financial assets of shadow banks represented 225 percent of global GDP, up from 150 percent in 2008, while bank assets, growing at a slower pace, stood at 175 percent. Over this period, hedge funds have doubled in value to represent 8 percent of GDP.

While some entities within the shadow banking system have diminished or vanished, many have thrived, with new actors emerging. Today, the landscape is largely dominated by asset managers—including insurance companies, pension funds, non-bank finance entities, and various investment funds. These groups invest client funds in public and private equity as well as hybrid securities. Additional players include securitization vehicles that restructure existing obligations into new securities, alongside specialized fintech firms, microloan organizations, trade financiers, payday lenders, pawn shops, and loan sharks. This is a global issue, with China displaying a particularly expansive array of shadow banks offering products like wealth management vehicles and various types of loans.

There are several common traits among these diverse operations. They serve as intermediaries, channeling capital flows from investors—including retail clients, high-net-worth individuals, family offices, institutions, and sovereign investment entities—to businesses. Utilizing a variety of trading strategies, they aim to profit through financial market transactions. Moreover, they operate with significantly less regulatory oversight than banks since they do not traditionally accept public deposits or participate in payment systems.

Current regulatory apprehensions regarding the shadow banking sector are often disingenuous, as policies support the expansion of these entities. Stricter banking regulations, such as those established by the Basel III accord post-2008, have curtailed lending, especially to small and medium enterprises, real estate, and various projects. This dynamic has facilitated the rise of shadow banks to fulfill unmet credit demands. Additionally, a prolonged period of low-interest rates from 2008 to 2021 has compelled investors to pursue higher returns across an evolving investment landscape. In Asia, banks’ difficulties in handling non-performing loans have likewise created obstacles to meeting loan demands, which fuels regulatory arbitrage driven by differences in capital, leverage, and liquidity standards.

The implications of these policy shifts are nuanced. Securitization has flourished partly because central banks—including the US Federal Reserve, the Bank of Japan, the Bank of England, and the European Central Bank—hold significant portions of government debt, effectively reducing availability. This scarcity supports demand for high-quality securitized debt as a safe asset and collateral for secured loans.

Interestingly, regulated banks have adapted to the rise of shadow banks by changing their business models to focus more on ‘moving’ rather than simply ‘storing’ assets. They are now able to leverage their capital more effectively, enhancing returns on shareholder funds by underwriting and distributing loans and other assets to funds and insurers. For central banks, this strategy increases the velocity of money within the economy.

In an attempt to circumvent restrictions on proprietary trading, many banks have established hedge funds led by former in-house traders. This approach enables banks to earn income from financial instrument trading while keeping these operations off their balance sheets, providing services like clearing and custody as additional revenue sources. Moreover, banks extend substantial leverage to these entities through asset-backed loans and unfunded derivatives, further increasing potential profits.

Banks often see returns from their investments in these funds, with their wealth management or private banking divisions offering structured products from these external entities.

The rise of shadow banks has profoundly transformed the financial system, presenting poorly understood risks. These institutions have the potential to drive debt levels higher, which may amplify asset price bubbles across various markets. The lucrative returns they promise indicate higher risks, especially as traditional banks prioritize lending to more secure borrowers. As a result, shadow banks may extend credit to lower-rated debtors or against riskier assets, often employing leverage beyond that of regulated institutions. This layering of leverage intensifies systemic risk, creating dependency on a flawed collateral system to mitigate credit risk—an arrangement that could unravel during economic downturns.

Compounding these challenges is the absence of permanent loss-absorbing capital, as many shadow banks operate as funds that redirect investors’ contributions. Liquidity concerns and redemption risks also loom large. To maintain investor returns, many shadow banks are compelled to remain fully invested, thereby creating minimal cash reserves. Significant mismatches between asset and liability maturities and holdings of illiquid assets may lead to pressure during a financial crunch, impacting entities such as pension funds and insurance companies by hindering their ability to meet contractual obligations.

There are notable connections between regulated financial institutions and their shadow bank counterparts. For instance, US banks have provided around $300 billion in loans to private credit entities, comprising a substantial portion of all loans. Additionally, banks have extended about $285 billion in credit to private equity funds and maintained $340 billion in unused commitments. They have also financed leveraged investors like hedge funds, with prime brokerage loans now reaching around $3 trillion. Estimates indicate that the total exposure of US and European banks to non-bank financial institutions nears $4.5 trillion.

This interconnection is primarily driven by differential capital treatment. Conventional bank loans are typically assigned a 100 percent risk weight, while loans to shadow banks may carry as low as a 20 percent risk weight, effectively reducing capital requirements for such exposure. Collateral management or financial engineering through securitization allows banks to hold senior positions in asset pools, mitigating initial losses. This dynamic makes lending to shadow banks a less capital-intensive option, which bolsters returns.

Rather than addressing the core issues, policymakers have sought to transfer risks from regulated banks to non-banks. They operate under the belief that challenges in the shadow banking sector can be contained, thus preventing them from affecting banks and avoiding unpopular public bailouts. Recent crises involving Greensill Capital and Archegos Capital—which impacted the downfall of Credit Suisse—highlight the complex reality and the heightened risks associated with shadow banks.

The most stringent regulatory measure would involve isolating shadow banks entirely, requiring 100 percent cash collateral for regulated entities interacting with them to curb exposure while enforcing strict no-bailout policies to limit moral hazard.

Conversely, a more moderate approach would emphasize oversight and regulation based on function rather than legal designation. This strategy would introduce a greater degree of flexibility in recognizing the distinctions among various entities, their activities, and their risk profiles. Depending on the activity type, minimum capital requirements, limits on leverage, and sufficient liquidity protections for potential redemptions would be necessary. Additionally, reliance on short-term funding could be restricted. Eligible sponsors would need to meet set standards for capital, expertise, and governance, and banks’ interactions with non-bank institutions, including lending and other operations, would also require regulation.

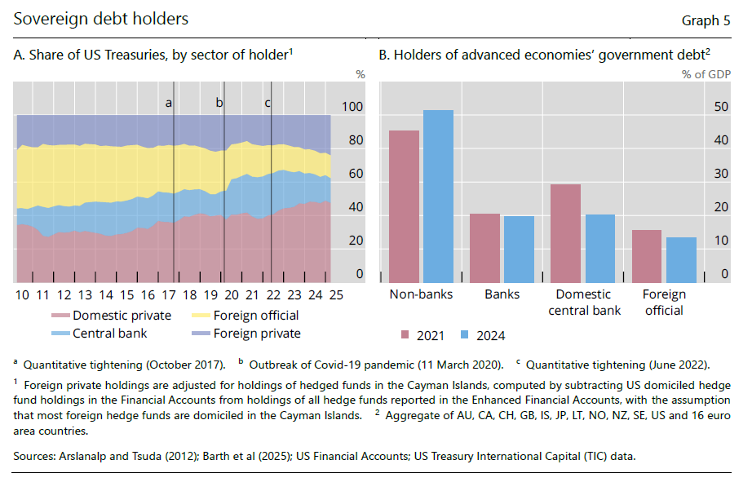

However, concerns about potential credit shortages and the financial sector’s lobbying power suggest that meaningful regulatory changes are unlikely. Concerningly, shadow banks have become substantial holders of government debt(refer to the graph below). Since 2021, their holdings of sovereign debt in advanced economies have surpassed 50 percent of GDP, compared to less than 20 percent for banks and central banks. Notably, hedge fund sovereign debt positions have more than doubled, reaching nearly $7 trillion, funded in part by repo borrowing that has nearly tripled to exceed $3 trillion.

This situation indicates a strong resistance to regulating shadow banks, as any such measures would necessitate confronting significant debt levels and altering a borrowing-driven economic model.

As the financial landscape continues to evolve, it is likely that in the next crisis, shadow banks will again exacerbate asset price declines, increase market volatility, and present a primary source of financial instability.

© Satyajit Das 2025 All Rights Reserved