In a recent discussion on YouTube with Gonzalo Lira, we explored the concept of “belief clusters,” where individuals sharing a particular viewpoint are often assumed to hold related opinions. A prime example of this can be seen within the anti-globalist commentary community on platforms like YouTube and Substack, which frequently portrays a binary narrative: a brutal, US-led hegemony clashing with a noble Global Majority striving for a more equitable world order. This oversimplification often contrasts US colonial exploitation with what is perceived as China’s more benevolent economic behavior.

However, our observations in Thailand and insights drawn from Africa suggest that the differences may be less pronounced, akin to the dichotomy between the Republican and Democratic parties in the US. As Lambert noted:

“The Republicans tell you they will knife you in the face. The Democrats say they are so much nicer, they only want one kidney. What they don’t tell you is next year, they are coming for the other kidney.”

Indeed, under Trump, the US has adopted an exceptionally piratical approach, making any alternative, including China, seem more appealing in comparison. It is crucial not to confuse “better by comparison” with genuinely good practices. Some commentators are waking up to this reality, as detailed in our extensive discussion titled “BRICS Are the New Defenders of Free Trade, the WTO, the IMF and the World Bank” and Support Genocide by Continuing to Trade with Israel.

Today, we will draw heavily from an insightful article by Patrick Bond, a professor of Sociology at the University of Johannesburg, entitled Africa deindustrialises due to China’s overproduction and Trump’s tariffs. It is noteworthy that this piece is hosted on the Committee for the Abolition of Illegitimate Debt website, which maintains an anti-neoliberal and anti-colonial stance, with Marxist leanings.

Bond’s analysis of China is grounded in thorough research and local perspectives. He references works like The Material Geographies of the Belt and Road Initiative, edited by Elia Apostolopoulou et al., which provide a comprehensive backdrop to his arguments. We quote Bond extensively, not only because his points are richly supported by evidence but also because he systematically addresses the views of Vijay Prasad, articulating why he categorizes Prasad as a “China optimist.”

From my observations in Southeast Asia, I find myself sympathetic to Bond’s perspective. The English-language media often tiptoes around sensitive issues, adhering to widely accepted narratives. This approach sometimes echoes local grievances about predatory Chinese business practices, such as those surrounding zero-dollar exports and zero-dollar factories. The recent imposition of tariffs by the US, prompting China to divert shipments through Southeast Asia, has compounded these issues, raising concerns not merely about tariff evasion but also about market dumping. This predicament is particularly alarming, given the established family and business connections between the Thai elite and Chinese interests. It would be reasonable to assume that countries in Africa might face even greater challenges.

While we’ll briefly summarize the damage attributed to Trump, a topic widely recognized by both anti-globalists and Trump critics alike, we will then delve into the less understood nuances of Chinese exploitation. Many misconceptions stem from equating China’s behavior with that of the Soviet Union, a misapprehension rooted in the idea that the latter lacked resource needs and profit motives. Contemporary China, however, does not share this stance.

Trump’s policies have undeniably inflicted harm on Africa. He and his white supremacist ally Elon Musk obliterated most US emergency food, medical, and climate-related aid to Africa, with South Africa experiencing even harsher cuts. On the trade front, Bond notes:

“Then came Trump’s devastating tariffs – in February, April, and again in August – followed by the September demise of the Africa Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), which since 2000 had granted numerous African countries duty-free access to U.S. markets. Despite the saving graces associated with AGOA largely benefiting energy and mineral exports rather than manufactured goods, the subsequent trade restrictions were particularly harmful, decimating 87% of auto exports from South Africa in the first half of 2025.”

The World Bank determined that the chaos of 2025’s tariffs would significantly impact industries tied to global supply chains, notably textiles, apparel, and automotive sectors across several African countries.

Demand from other Western nations is also expected to stagnate due to new European regulations and sluggish growth.

Bond’s article features a compelling analysis of China’s overinvestment and overcapacity issue, positioning it as a classic case of Marxist capital overaccumulation. He explains how the Belt & Road Initiative, initiated in the early 2010s, enabled Chinese firms to address their domestic overproduction struggles by expanding operations along its pathways.

In addressing the global issue of overproduction, Bond presents key statistics:

“Most notably, excess capacity serves as a glaring indicator, evidenced by specific sectors:

Global steel output reached nearly 1.9 billion tonnes in 2024, compared to a staggering 2.47 billion tonnes of capacity (with only 76% of that capacity utilized), with a further 10% expected increase in excess capacity in 2025, resulting in 680 megatonnes;

According to Bloomberg News, the emergence of new Chinese petrochemical plants has sparked concerns about an impending glut of exports that could burden other struggling producing nations;

China’s annual vehicle production capacity reached 55.5 million vehicles in 2024, but only 50% was utilized (producing 27.5 million vehicles that year), with projections suggesting an output of 35 million in 2025, thus displacing other economic sales while leaving the global auto market flooded;

Furthermore, “The cement sector’s troubles are rooted in a persistent issue of overcapacity, exacerbated by weakening market demand,” report the China Building Materials Federation, pointing to declining property investments and a slowdown in infrastructure.

In 2024, solar photovoltaic panels generated approximately 600 GW of new power, predominantly sourced from China, yet over 1,000 GW of manufacturing capacity existed, with lithium-ion batteries produced at a scale of 2.5 TWh in 2023, expected to reach 3 TWh in 2024, while demand was projected to rise to only 5 TWh by 2030.

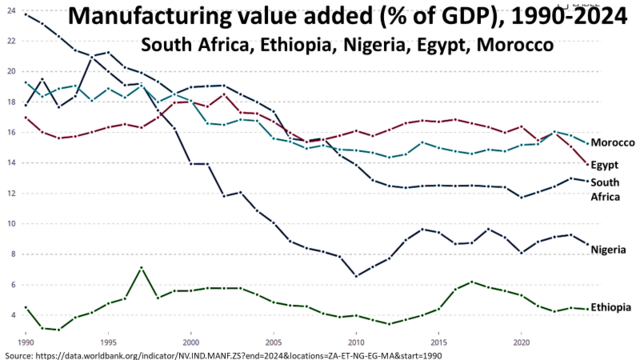

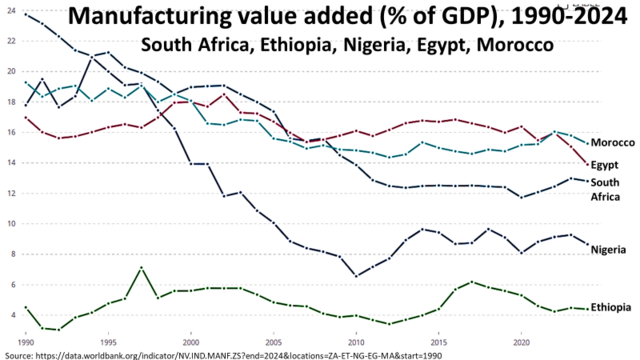

Bond elaborates that even the most industrialized African nations have seen their manufacturing sectors shrink in significance. For instance, even Ethiopia—a so-called success story—has witnessed substantial declines in its manufacturing contributions. He states:

“There are numerous instances of negative impacts resulting from Chinese capitalism in Africa: deindustrialization due to flooding local markets with surplus goods, broken promises regarding investments in Special Economic Zones, unchecked corruption, excessive lending followed by sudden credit reductions, and egregious corporate behavior, especially in the extractive sectors, resulting in severe ecological degradation.” Bond’s assertion deserves in-depth exploration, as outlined in the sections that follow.

One glaring case is South Africa’s rapid deindustrialization, largely attributed to the dumping of Chinese surplus goods, which has prompted governmental responses, including tariffs on imported Chinese steel and appliances. According to reports, South Africa’s manufacturing-to-GDP ratio plummeted from 24% in 1990 to just 13% today.

Intense competition from Chinese products has meant the African nations cited by Prasad, recognized as industrial production hubs and the continent’s largest population center (i.e., Nigeria), have failed to enhance their manufacturing/GDP ratios since the 2015 FOCAC industrialization hype. Most ratios, similar to South Africa’s, had already deteriorated following the trade liberalization wave of the 1990s.

The prime case of Ethiopia was once lauded as a beacon of African industrialization, primarily due to a surge in (largely sweatshop) manufacturing in Addis Ababa, which benefited from new infrastructure linking to the port of Djibouti, with Chinese investment playing a crucial role. While Ethiopia’s manufacturing/GDP ratio rose sharply from 3.4% in 2012 to 6.2% in 2017, it fell to 4.3% from 2021 to 2024. The International Monetary Fund noted that the share of manufactured goods in Ethiopia’s total exports, such as textiles and leather, rose from 13.5% in fiscal year 2018/2019, only to plummet to around 4% in the first nine months of fiscal year 2024/2025 due to a myriad of factors, including pandemic impacts, conflict, and currency shortages.”

These financial strains culminated in a significant crisis in late 2023, prompting Ethiopia’s initial disqualification from becoming a formal member of the BRICS New Development Bank, which is critical for hard currency funding, although it plans to join in the future.

Will Beijing intervene? Chinese aid, investments, and loans to Africa have also declined since their peak mid-2010s, affecting many countries’ foreign reserves. Chinese public and publicly-backed loans dropped sharply from $32 billion at their height in 2016 to just $1 billion in 2022, culminating in an African foreign debt totalling $1.3 trillion, of which $182 billion is owed to China.

Moreover, Bond critiques the popular belief that China is benevolent in its debt restructuring efforts for Belt & Road borrowers in distress. This viewpoint reflects a misunderstanding, as it ranks something less damaging than IMF “rescues” as favorable. He asserts that poorer African nations often face harsher treatment compared to middle-income countries:

“China’s new public and publicly backed loans to Africa plummeted from $32 billion in 2016 to $1 billion in 2022. The $1.3 trillion in African foreign debt by 2025 includes $182 billion tied to China’s known loans. Between 2021 and 2024, China funded 128 rescue loan operations totaling $240 billion in 22 low-income nations, including five African states. Such countries received primarily grace periods or repayment extensions, while middle-income states, were more likely to get new funding to delay default. Many low-income borrowers were stuck with repeated short-term loan extensions to service maturing debts.”

While the 2024 FOCAC did increase financial flows in the Chinese currency—which could help facilitate trade and ease currency shortages—caution is warranted. The Centre for Global Development, generally supportive of Chinese lending, highlights that:

“Between 2015 and 2021, commercial lenders contributed about a third of all Chinese lending commitments, surpassing state banks for the first time. These commercial lenders are market-driven, offering less favorable and shorter-duration loans than state-backed counterparts. Their requirement for risk mitigation, often through Sinosure, heightens financing costs. Should this pattern continue, rising commercial lending at non-concessional rates will further increase the risk of debt distress in Africa.”

Bond raises a contentious issue among left-leaning and anti-globalist circles: the notion that China is essentially pillaging Africa to secure resources. This inquiry gains credence given China’s growing foothold on the continent, even as manufacturing value additions dwindle in the more industrialized countries. He counters arguments made by defenders like Vijay Prasad, suggesting that competition from Chinese firms has supposedly yielded better terms for African nations reaping the benefits while leveraging their resources for products aimed at first-world markets. This mirrors the sentiment of “coming for your kidneys over two years looks less bad than being knifed in the face.” From the article:

“There are often three categories to consider regarding ecological reparations linked to non-renewable resource depletion, greenhouse gas emissions, and localized pollution. This subimperial positioning within global value chains renders China susceptible to critiques of unequal ecological exchange. Behind the necessity for resource extraction, shocking conditions prevail. Without veering into Sinophobia, it is helpful to recall some notorious instances, as China fails to address the evident need to curb exploitative practices by its firms involved in the Belt and Road initiative:

In the DRC, illegal pollution from Congo Dongfang International Mining tainted the Lubumbashi River while informal miners suffered casualties due to unsafe working conditions, compounded by non-compliance regarding overdue royalties owed to the government.

In Zambia’s copperbelt, negligence by Sino-Metals Leach led to an environmental disaster, releasing cyanide-laden sludge into the Kafue River, prompting a major lawsuit from affected residents.

In the Central African Republic, reports emerged of human trafficking by Rado Central Coal Mining Company, where Nigerian workers went unpaid for extended periods.

In Ghana, violations by Shaanxi Mining exacerbated the artisanal mining crisis, while in Zimbabwe, various Chinese companies were accused of egregious human rights violations within the mining sector.

In South Africa, instances of corruption by Chinese locomotive suppliers and criticisms of their unmet commitments to job creation have surfaced, alongside numerous complaints regarding ecological exploitations at various mining sites across the nation.

These troubling incidents encapsulate a broader pattern of unequal ecological exchange where African economies suffer net losses, despite some gains in foreign exchange and national income. Generally, the costs associated with local pollution, displacement, and depletion of non-renewable resources significantly overshadow any potential advantages.

Add extensive social costs in the form of carbon emissions from mines and smelters, exacerbating the situation. Such ecological ramifications may lead to the creation of new “polluter-pays” climate debtors from low-income African economies, particularly if international legal standards for socio-ecological reparations gain ground.

In summary, unless the Chinese state takes decisive action to regulate its companies’ emissions and resource exploitation practices in Africa, along with addressing the pressing need for ecological reparations, it is improbable that genuine industrialization initiatives will arise from Chinese investments on the continent.

Thus, those who wish to envision China as an enlightened economic power may need to reassess their perspective. Notably, even an economist with established ties to China confided to me, “Now that I am in Thailand, I have a significantly less optimistic view of Chinese investments,” reflecting the pervasive concerns surrounding the reputation of Chinese business practices throughout Asia.

“That’s why Chinese businessmen were often viewed unfavorably across Asia. Even Chinese officials have boasted to me about their cutthroat tactics in business.”

In the past, Wall Street characterized its practices as “long-term greedy,” a fitting description for China’s mercantilist approach. It serves as a reminder: being “long-term greedy” still equates to being greedy.