In today’s rapidly changing energy landscape, nuclear power is undergoing a significant transformation. As the world grapples with rising electricity demands and the limitations of renewable energy sources, Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) have emerged as a promising solution. Below, we explore the economic and technological challenges and opportunities surrounding this advancement in nuclear energy.

By Michael Kern, a newswriter and editor at Safehaven.com and Oilprice.com. Originally published at OilPrice

- The transition to Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) is fueled by increasing global electricity demand, particularly driven by AI data centers, highlighting nuclear power’s role as a vital source of constant and reliable baseload energy.

- SMRs reduce the financial risks associated with traditional large-scale nuclear projects like Vogtle by offering shorter construction periods (3 to 5 years) and lower initial costs, relying on factory-produced components for “economies of unit production.”

- Significant hurdles for the SMR sector include the necessity for mass production to achieve cost-effectiveness, addressing waste management concerns, and navigating geopolitical risks tied to a concentrated global uranium supply chain.

Currently, nuclear energy is experiencing a renaissance akin to the rise of Silicon Valley. After being perceived for decades as slow, costly, and politically unfeasible, the industry has shifted towards Small Modular Reactors (SMRs). This pivot aims to transition from constructing large energy facilities to developing compact, efficient energy systems.

Market dynamics are now aligned for a transformational phase. Global electricity consumption is growing at double the rate of overall energy demand, propelled by the increasing proliferation of AI data centers and the gradual electrification of transportation. The output from the world’s fleet of nearly 420 reactors is projected to hit a record high in 2025, as there is a collective understanding that intermittent renewable sources alone cannot sustain a 24/7 civilization.

The need for baseload power has evolved into a requirement for economic participation in today’s world.

Small Is the Key to Big Nuclear’s Survival

First, “Small” describes reactors that generate up to 300 MWe, which amounts to roughly a third of the output of conventional gigawatt-scale plants—sufficient to power around 250,000 homes or significant industrial operations.

Second, “Modular” is where the true economic advantage lies. Rather than designing each component at a construction site, factory-produced components are pre-manufactured and delivered to the site.

Finally, “Reactor” indicates a departure from merely downsized versions of outdated technologies. We’re witnessing a transition to Generation IV innovations, such as molten salt reactors without meltdown risks due to liquid fuel and gas-cooled reactors capable of delivering the high temperatures required for steel or hydrogen production.

Why Megaprojects Failed in Georgia

Traditional nuclear undertakings, like the Vogtle plant in Georgia or Hinkley Point C in the UK, have gained notoriety for their excessive costs and prolonged timelines. These plants are not merely energy generators; they reflect decades-long engineering challenges that deplete financial resources faster than they can produce electricity.

The Vogtle project ultimately cost over $30 billion—almost double the initial estimate.

No private investor is keen to shoulder a $30 billion liability for years before generating revenue. SMRs aim to avoid this “Valley of Death” by reducing construction timeframes to 3-5 years and bringing down initial investment levels to a point where mid-sized utilities or tech firms can realistically participate.

It represents an effort to exchange “economies of scale” for “economies of unit production.”

The East is Advancing While the West Deliberates

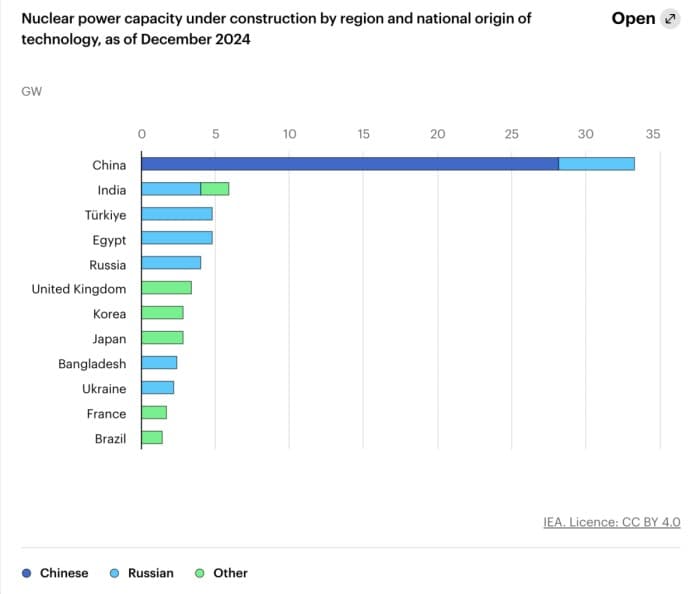

The “Nuclear Renaissance” is already taking place; it simply hasn’t reached Western countries yet. Of the 52 reactors that began construction since 2017, nearly half are located in China, while the other half can be found in Russia.

(Source: IEA)

The real bottleneck lies not in technology but in fuel availability. Currently, Russia dominates approximately 40% of the global uranium enrichment capacity. Relying on them for uranium presents significant energy security challenges.

A.I. Requires Nuclear Power to Keep Up

Tech corporations aren’t investing in nuclear energy merely out of an appreciation for carbon-free baseload power; they are facing an energy crisis of their own. For instance, a single query on ChatGPT consumes around ten times the electricity of a standard Google search.

Amazon, Google, and Microsoft have acknowledged that wind and solar can only provide “part-time” energy—when the sun isn’t shining or the wind doesn’t blow, the demand of data centers continues unabated. This creates a substantial issue known as “intermittency,” which current battery technology cannot effectively manage at a large scale. The SMR stands out as the only viable solution offering reliable 24/7 power generation with a compact footprint suitable for installation beside server farms.

For the first time in history, the primary motive behind nuclear energy demand is originating from the private sector rather than state initiatives.

These companies possess the creditworthiness and long-term outlook to guarantee “offtake,” which is crucial for SMR manufacturers to kickstart their production lines.

By entering into 20-year Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs), they provide the necessary bankability that enables SMR producers to begin operations.

Identifying Success in an Industry Full of Failures

The SMR sector has been fraught with promising concepts that ultimately fell short due to lack of funding. To emerge victorious, a company must possess three critical elements: a straightforward design, a licensed site, and a financially robust customer.

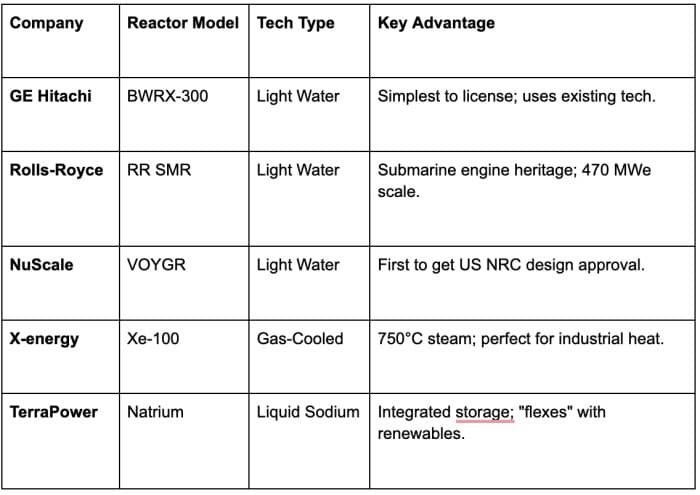

The market is divided between the established “Old Guard” refining proven technologies and “Disruptors” focused on Generation IV advancements.

The $2,500/kW Goal: Competing with Chinese Costs

This is typically where marketing narratives lose touch with reality. Constructing a single SMR can result in the highest electricity costs on the planet. The modular promise only materializes when modules are produced at scale, similar to airplane manufacturing.

The IEA forecasts that investments in SMRs will surge to $25 billion annually by 2030. However, constructing the first factory for these modules could consume a significant chunk of this budget before any reactors are shipped. The learning curve for SMRs poses considerable financial challenges, with studies indicating that “learning-by-doing” can decrease capital costs by 5% to 10% for each doubling of production. Yet a report from Germany’s BASE suggests that at least 3,000 SMRs need to be built before the industry achieves true economies of mass production.

This represents the crux of the industry’s challenge. No CEO wants to declare they are the pilot for an unproven $1 billion reactor.

Relying solely on private investment is insufficient. The lengthy permitting process means the express “breakeven point” for large reactors often extends beyond 20-30 years. While SMRs cut this timeline in half, attracting commercial lenders remains a difficult task.

Here, Green Bonds and Public-Private Partnerships come into play.

To date, over $5 billion in green bonds have been issued for nuclear projects, and the U.S. DOE’s Advanced Reactor Demonstration Program is allocating billions to prototype projects. However, the real pathway across the “Financial Valley of Death” is the credit worthiness associated with major tech companies. When Google or Amazon enters into a 20-year PPA, the associated debt becomes more financially viable.

Designing Safety into Nuclear Energy from the Ground Up

Proponents of SMRs emphasize “passive safety”—designs that utilize natural physics (gravity and convection) to ensure reactor cooling even without power. This is essentially a form of “Fukushima-proofing.” Due to their smaller size, these units possess lower radioactive inventories per reactor, allowing them to be situated at retired coal plants. The advantages include:

- Gravity-Driven Cooling: In the event of a power loss, cool water is naturally drawn into the reactor core.

- Reduced Radioactive Inventory: Smaller reactor cores lead to a significantly decreased exclusion zone.

- Underground Installation: Positioning reactors below ground provides a natural barrier against external threats.

Nevertheless, waste management continues to present challenges. A 2022 Stanford study suggested that SMRs might generate more waste per unit of energy due to the tendency of smaller cores to leak more neutrons, increasing radioactivity in the surrounding structure over time. The industry’s counterargument posits that this waste could be repurposed as fuel in future breeder reactors. Both arguments have merit, but the requisite breeder technology is not yet available.

If we deploy thousands of SMRs to remote mining operations or developing nations, we risk widespread nuclear material dispersion. This creates a daunting security challenge. A proposed solution is the “Battery-Style” SMR: constructed, fueled, and sealed in a factory, delivered to its destination, operated for 20 years, and then returned, ensuring the end-user never directly handles nuclear fuel.

Reforming Nuclear Regulation to Keep Pace with Innovation

The U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) was established to oversee large, one-off light-water reactors. Applying the regulatory framework of the 1970s to 2025 technology is akin to trying to license a Tesla using steam engine regulations.

In July 2024, the ADVANCE Act was enacted, specifically instructing the NRC to expedite the approval process for microreactors and SMRs. By December 2025, the NRC had completed 30 out of its 36 anticipated tasks under this legislation—a move aimed at mitigating the “licensing-by-exhaustion” approach that has derailed numerous projects in the past.

International harmonization is the next critical step. If a reactor design receives approval in Canada (such as the BWRX-300), why should it undergo another five-year, $100 million review in the U.S. or UK? As strategic leadership takes root in concrete, Western nations find themselves lagging in policy consensus.

The $1.5 Trillion Opportunity for Industrial Heating

Many associate nuclear power primarily with electricity generation, yet electricity constitutes only 20% of global primary energy demands. The larger concern is Industrial Process Heat. High-temperature heating is essential for producing steel, cement, and glass—temperature requirements that wind and solar cannot meet without significant efficiency losses. Presently, fossil fuels satisfy 89% of this high-temperature demand.

The SMR, particularly the High-Temperature Gas Reactor (HTGR), presents the only zero-carbon option capable of integrating with chemical plants to generate 750°C steam. According to a 2025 study by LucidCatalyst, the potential market for industrial SMRs could reach 700 GW by 2050.

This could represent a $1.5 trillion investment opportunity.

The top markets are not utilities; they include synthetic aviation fuels, coal plant repurposing, maritime fuels, data centers, and chemical production.

In October 2025, the European Commission initiated its first pilot auction for decarbonizing industrial heat. Companies like France’s Blue Capsule are developing reactors specifically targeting this niche.

If SMRs fail to penetrate the industrial heating market, achieving Net Zero may prove mathematically impossible.

Desalination in the Middle East: A Potential Game-Changer

In the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), the link between energy security and water security is undeniable. Arab nations currently produce over half of the global desalination capacity. Desalination requires substantial energy, and historically, has relied heavily on oil and gas. However, nations in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) have set ambitious net-zero goals by 2050–2060.

SMRs offer a dual-purpose solution: supplying baseload electricity for grids while providing the vast amounts of heat or electricity required for Reverse Osmosis (RO) or Multi-Effect Distillation (MED).

In Jordan, an IAEA team recently assessed the use of SMRs to produce potable water from the Red Sea for Amman. Meanwhile, in Saudi Arabia, the world’s leading desalinated water producer, the government is exploring nuclear energy as a cornerstone for transitioning away from an oil-dependent economy.

The financial feasibility is improving. Using the Desalination Economic Evaluation Program (DEEP) model, 2025 data indicates that high-temperature helium-cooled reactors can produce desalinated water at a commercially viable cost of $0.69 to $1.04 per cubic meter.

Microreactors: The Next Generation of Energy Solutions

While 300 MWe reactors garner significant attention, a segment of the industry is pursuing even smaller innovations. Microreactors (under 10 MWe) aim to function as “nuclear batteries” in the most challenging environments on Earth.

The U.S. Department of the Air Force is a primary customer in this sector. In May 2025, they announced plans to contract with Oklo, Inc. for a microreactor pilot project at Eielson Air Force Base in Alaska.

Why Alaska, you may ask?

Transporting diesel to remote Arctic bases is not only expensive but also hazardous, with considerable logistical challenges.

The Eielson project features a 30-year PPA under which the vendor will own and operate the reactor, ensuring “Mission Assurance” in extreme cold conditions. However, interest extends beyond military applications.

Remote mining operations in Canada and Australia are also considering microreactors such as the eVinci (developed by Westinghouse) or the KRONOS (from Nano Nuclear). For mines that currently expend $50 million annually on diesel fuel, a microreactor with a decade-long operational period without refueling presents more than just an environmentally friendly choice—it represents a significant competitive edge.

Fuel Security: Navigating Risks in Kazakhstan and Niger

Next, we must address the fuel supply issue. The entire discussion hinges on HALEU (High-Assay Low-Enriched Uranium), and the associated supply chain is laden with geopolitical risks. Kazakhstan is currently responsible for over 43% of the world’s uranium, which raises serious concerns about supply concentration, especially given recent civil unrest in the region.

Additionally, tumultuous political developments in Africa, such as the 2023 military coup in Niger, have disrupted reliable uranium supplies, leading to a lack of reported production in 2025 from the SOMAÏR mine.

The West is starting to take action. By late 2025, Urenco USA successfully enriched uranium above 5% in New Mexico. Centrus Energy initiated commercial enrichment efforts in Ohio, aiming at HALEU production to address a $2.3 billion backlog. However, it can take 7–10 years to develop new mines. As of now, we are facing a “seller’s market,” with uranium prices hovering between $86 and $90 per pound in new contracts. Without diversifying the fuel supply, the SMR movement may falter before it gains traction.

Addressing the Duck Curve

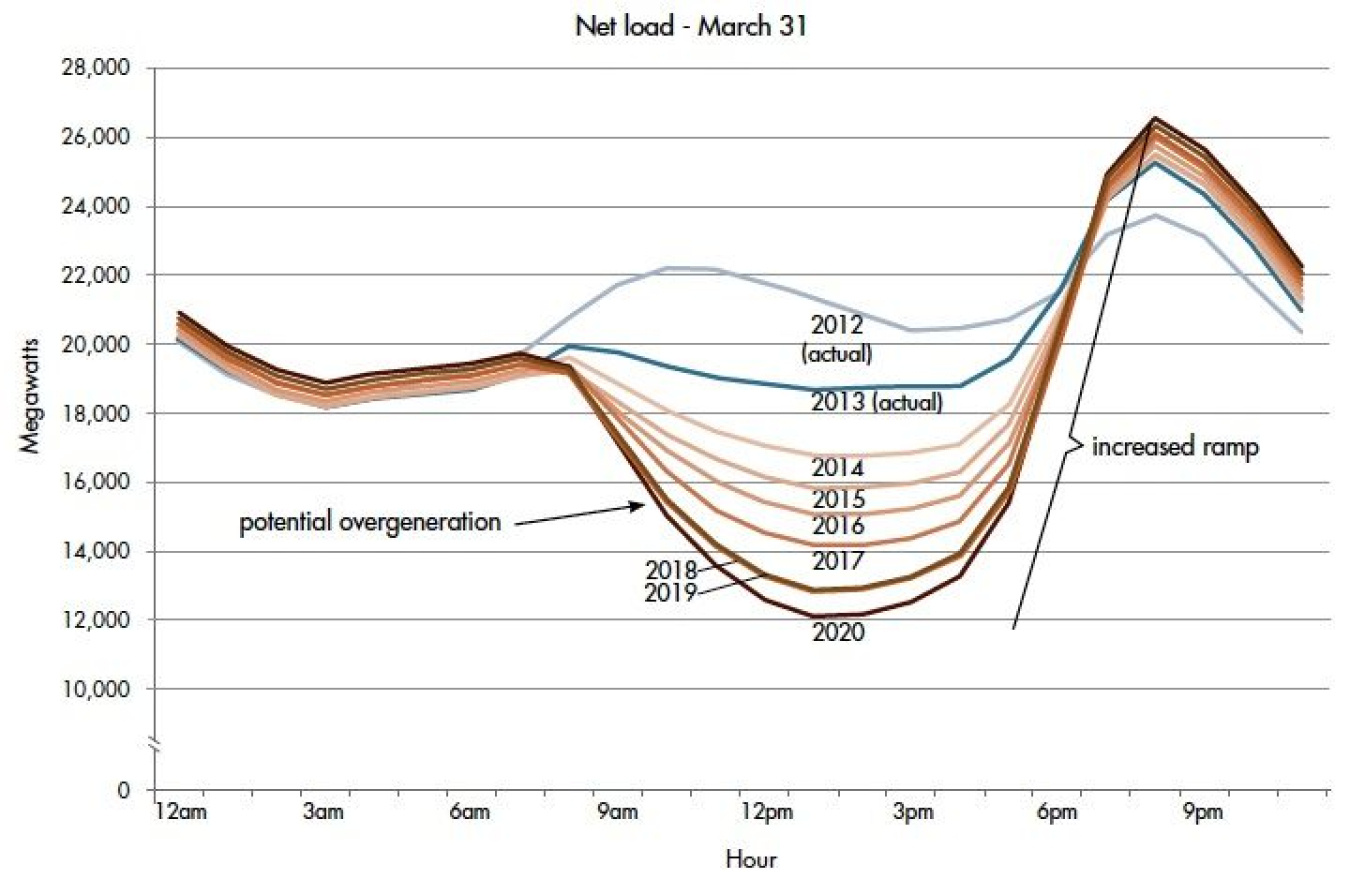

The contemporary energy grid is grappling with the “Duck Curve,” a significant disruption in supply associated with the variable nature of solar and wind energy.

(Source: DOE)

Historically, nuclear energy has been viewed as a rigid baseload source—operating continually at full capacity for extended periods.

However, SMRs are designed with Load-Following capabilities, allowing them to adjust output as demand fluctuates.

For example, TerraPower’s Natrium reactor includes a molten salt heat storage system. This design enables the reactor to maintain a stable temperature while the storage manages the electrical output based on grid demand. When solar energy is abundant, the reactor stores heat, and when the sunlight fades, it releases it to generate electricity.

This effectively converts the nuclear reactor from a “firm floor” into a “flexible battery,” closing a vital gap in renewable energy strategy. Lacking this flexibility compels reliance on gas-fired “peaker” plants, undermining carbon-free objectives.

Transforming the Rust Belt: Shifting from Coal to Nuclear

The U.S. is home to over 300 retired or decommissioned coal power plants. These locations are energy treasure troves, already equipped with grid ties, cooling water access, and, most critically, a skilled workforce adept at managing thermal power operations.

SMRs represent the ideal technology for reactivating these sites without necessitating extensive economic restructuring.

For example, NuScale is partnering with Dairyland Power in Wisconsin to assess the feasibility of implementing VOYGR plants at decommissioned coal facilities, thereby preserving high-paying jobs in communities at risk of economic decline due to the shift away from coal. This transformation turns a liability (a defunct coal plant) into a 60-year asset.

A Crucial Five Years Ahead: Meeting the 2030 Benchmark for Assembly Lines

We are transitioning past an era defined by “paper reactors.” By the conclusion of 2025, the nuclear sector is focusing intently on three key aspects: Licensing, Supply Chain, and Offtake. The technology is no longer the central concern; the emphasis has shifted to the factory.

The IEA’s APS scenario forecasts a need for 120 GW of SMR capacity by 2050. Without current policy adjustments, only 40 GW will likely materialize. The gap between these predictions signifies the difference between an effective and inefficient electrical grid.

The next five years (2025–2030) will undeniably be the most pivotal period in nuclear energy’s history. Although SMRs are not a definitive solution, they represent the only viable path to achieving a clean electricity grid. For manufacturers to reach a production pace of just one unit per month, the associated learning curve could diminish costs toward the $4,500/kW target.

Should they remain entrenched in a “bespoke project” mentality, they risk joining the illustrious graveyard of 20th-century energy experiments.

The stakes have never been higher.

Given the voracious energy demands of AI and the global cry for clean industrial heat, SMRs are no longer merely an option.

For a carbon-neutral industrial civilization, they might represent the final strategic move available. An atomic renaissance is unfolding; the pressing question remains whether the West can expedite its construction to have a meaningful impact.