Introduction: The recent ousting of Nicolás Maduro from the presidency marks a pivotal moment for Venezuela, a country that has experienced over two decades of socialist governance. The shift presents both challenges and opportunities as the nation seeks a path toward recovery and revitalization.

The removal of Nicolás Maduro from Venezuela’s presidency is a significant turn of events following more than twenty years of socialist rule under Hugo Chávez and Maduro, marked by expropriation, poor economic management, and political oppression.

While the economic and political future of Venezuela remains uncertain, insights from economics can provide some guidance—and crucial warnings. One such insight emphasizes the peril of relying solely on the oil sector for economic recovery. The nation’s future is heavily reliant on its institutional and policy decisions moving forward.

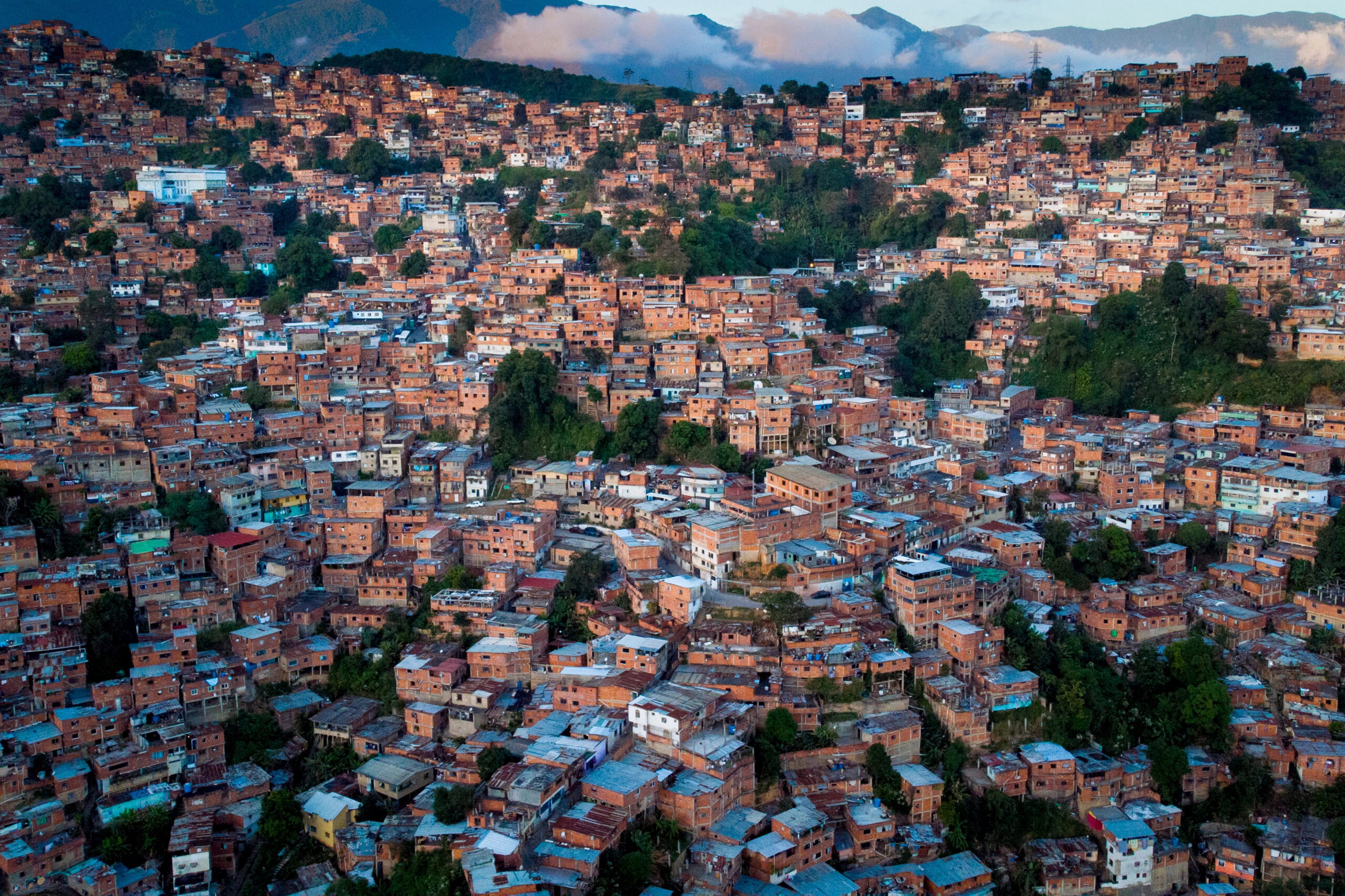

Currently, Venezuela’s judiciary, electoral authorities, public prosecutors, and police lack independence. The first imperative must be the restoration of individual and political rights through the reform of these key institutions, enabling the Venezuelan people to hold their political leaders and government agents accountable.

Additionally, it is vital to reinstate private property rights and encourage free enterprise to unleash the creativity of the Venezuelan populace.

Finally, leadership must prioritize the establishment of foreign-exchange policies and the management of oil revenues, which are essential in avoiding a renewed cycle of dependency, rent-seeking behavior, and stagnation.

A political transition that incorporates genuine electoral reforms and credible assurances of fair competition would likely foster a gradual normalization of U.S. relations. This could lead to the easing of sanctions and renewed participation of private—especially foreign—oil companies in Venezuela’s energy sector. Given the country’s vast proven reserves and deteriorating yet recoverable infrastructure, even minor institutional enhancements could yield substantial increases in oil production and export revenues. Such revenues would present a rare opportunity to stabilize public finances, initiate repayment of defaulted foreign debts, and restore Venezuela’s standing in international capital markets.

Nevertheless, this opportunity comes with notable risks. The foremost of these is the threat of Dutch disease—the tendency of resource booms to elevate the real exchange rate, undermine non-resource tradable sectors, and entrench a non-diversified economic structure. Venezuela’s historical experience serves as a cautionary tale. Past oil booms resulted in exchange-rate appreciation and fiscal irresponsibility, which decimated agriculture and manufacturing, increased reliance on imports, and strengthened the political power of rent-seeking coalitions. Therefore, any serious reconstruction strategy must prioritize exchange-rate policy as a central tenet of economic reform.

To mitigate Dutch disease, it is essential to resist prolonged appreciation of the local currency, even amid rising export revenues, as I have previously argued elsewhere. A freely appreciating currency could render non-oil exports uncompetitive and hinder the resurgence of sectors vital for long-term growth and job creation. This does not necessarily mean reinstating stringent exchange controls—whose disastrous effects in Venezuela are well-documented—but instead emphasizes the need for a thoughtfully crafted system. Measures such as sterilizing foreign-exchange inflows, building external assets, and implementing institutional mechanisms to limit excessive domestic spending of oil revenues would all contribute to maintaining an advantageous real exchange rate.

Closely tied to the successful design of foreign-exchange policy is the management of oil rents. The main economic challenge for a post-socialist Venezuela will be to prevent these rents from being appropriated by established interests, whether public or private. In the absence of credible constraints, oil revenues tend to fuel corruption, clientelism, and fiscal irresponsibility, undermining both democracy and economic freedom. Therefore, establishing a dedicated “sink fund” deserves serious consideration. Unlike a conventional sovereign wealth fund aimed at maximizing returns or stabilizing consumption, a sink fund would have a narrow and transparent purpose: the systematic repayment of Venezuela’s foreign debts over a foreseeable timeline.

Allocating a significant portion of oil revenues to such a fund would yield several benefits. First, it would alleviate immediate domestic spending pressure, promoting exchange-rate stability and helping to avert Dutch disease. Second, it would aid in restoring Venezuela’s reputation as a responsible borrower, reducing future borrowing costs and enhancing access to international finance. Lastly, by placing oil rents beyond the discretionary control of daily politics, it would limit opportunities for rent-seeking and demonstrate a credible commitment to fiscal discipline.

Over time, reestablishing the core protections for private property and free enterprise would facilitate the recovery of economic activities outside the oil sector. Venezuela previously boasted a relatively diversified economy by regional standards, with significant capabilities in agriculture, manufacturing, services, and human capital-intensive industries. Although much of this capacity has been destroyed or pushed into the informal sector, it has not disappeared entirely. The Venezuelan diaspora—now numbering in the millions—represents a crucial reservoir of skills, entrepreneurial spirit, and international networks. If institutional reforms prove credible and durable, many expatriates may opt to return or invest from abroad, speeding up the process of reconstruction and diversification.

Potentially, the political demands of a struggling populace for public assistance could be redirected by fostering profit-making and income-generating opportunities within the private sector. Failing to understand and implement these changes could lead to an irresistible tendency toward rent-seeking, resulting in the misappropriation of oil rents and the corruption of political representation as government revenues become detached from the broader welfare of the Venezuelan populace and their economy.

In this broader context, exchange-rate policy and oil-rent management should be regarded as enabling conditions for a more profound transformation. The ultimate aim goes beyond mere macroeconomic stabilization; it is the reconstitution of a society where economic opportunity is divorced from political privilege. By avoiding currency overvaluation, shielding oil revenues from exploitation, and prioritizing debt repayment over short-term consumption, a post-Maduro Venezuela could lay the groundwork for sustainable growth and genuine reintegration into the global economy.

Accomplishing this vision will not be easy, and success will rely significantly on both luck and political will as much as on thoughtful policy design. However, if the conditions of political normalization, institutional reform, and renewed oil production come to fruition, the prudent management of exchange rates and rents could help ensure that Venezuela’s next encounter with resource abundance results in recovery instead of another squandered opportunity.

Leonidas Zelmanovitz is a Liberty Fund Senior Fellow and a part-time instructor at Hillsdale College.